Drawing on ideas and styles passed from vibrant Middle East trading cities into the West, the architectural heritage of Europe — and America — owes an important debt to the Arab and Islamic world, as I lay out in my new book, Stealing from the Saracens: How Islamic Architecture Shaped Europe. England’s greatest architect, Sir Christopher Wren, wrote that what we call "the Gothic style should more rightly be called the Saracen style.” Americans, it seems, are especially fond of Gothic. Across the continent are spectacular Gothic Revival structures, many modelled on the medieval cathedrals of England and France, such as St. John the Divine and St. Patrick’s in New York City, Washington National Cathedral, and the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Savannah, GA. On top of that, America boasts the world’s biggest collection of neo-Gothic architecture in its universities, colleges, and schools. What accounts for that popularity?

America’s leading neo-Gothic architect, Ralph Adams Cram, wrote in his book Gothic Quest about the power of architecture “to bend men and sway them.” Like the fervent European Gothic Revival architects before him, such as Augustus Pugin, designer of the clock tower commonly known as Big Ben for the Houses of Parliament in London, Cram believed that Gothic was the “purest” form.

While studying classical architecture in Rome, he had an epiphany during a Christmas Eve mass, thereafter becoming an Anglo-Catholic. Like his fellow neo-Gothic enthusiasts in Europe, and indeed like many Europeans today, for him Gothic architecture epitomized the Catholic faith. The commonly held view of Gothic’s provenance was that it represented Europe’s shared heritage. Although such Eurocentrism remains deeply rooted, serious scholarship has questioned just how “European” the Greek, Roman, and Byzantine civilizations that preceded the era of Gothic actually were, since all three empires were multicultural and multiethnic. Few of the later Roman emperors were ethnically Italian and even fewer Byzantine rulers were ethnically Greek.

The Islamic roots of Gothic architecture

The time has come to examine Gothic in the same way, since Cram never realized, along with Americans and Europeans in general, that key elements of Gothic architecture — the pointed arch, the trefoil arch, ribbed vaulting, and many other features — were born, not in Europe, but further east, often evolving from styles that were associated with a completely different religion.

Even Eurocentric architects cannot deny that the pointed arch had its origins in Islamic architecture. It appeared in the 7th century Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, built as the first Muslim shrine by the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik, and was then further developed under the Abbasids in Baghdad.

It went on to become the defining feature of Islamic religious buildings. The trefoil arch, so enthusiastically adopted by Gothic architecture as a symbol of the Holy Trinity, first appeared as a carved decorative feature in Umayyad shrines and desert palaces. Byzantine church architecture, which the Umayyad caliphate inherited, had round Roman arches and single domes, like Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia. There was not a pointed or trefoil arch in sight, let alone ribbed vaulting.

From Syria and their capital Damascus, the Umayyads brought these elements to Spain in the 8th century, re-using them in their main mosque of Cordoba, still known today as the Mezquita, Spanish for “mosque,” even though it was converted to a Catholic cathedral at the Reconquista. The 10th century ribbed vaulting of the Mezquita’s main dome, today called the Villaviciosa Chapel, was analyzed in 2017 by Spanish architectural engineers and pronounced the most perfect example of geometry, never once needing repair in its thousand-year existence.

The masons’ marks displayed on the rear wall show the names to be overwhelmingly Muslim, unsurprisingly, since their grasp of geometry and their stonemasonry was recognized as far superior to that of their European counterparts. It was no coincidence that Spanish Christian kings like Alfonso XI and Pedro the Cruel insisted on Mudéjar (Muslim) craftsmen for their building projects.

From Spain, these skills and styles passed into southern France where they were gradually incorporated into Benedictine abbeys and Cluniac shrines on the pilgrim route to Santiago de Compostela. The same styles also found their way into Europe from vibrant Islamic cities like Cairo, Damascus, and Aleppo, passing first via Italian trading ports like Amalfi, then via the Norman, Arab-influenced architecture of Sicily.

The returning Crusaders, ironically, set up new kingdoms in the 12th century, mimicking the styles of their conquered enemies, whom they called the Saracens, meaning “people who steal.” The Norman French brought the styles back to Normandy, where they synthesized them into what was originally just called “French work” in cathedrals like Notre-Dame and Chartres, before importing the style into England, under Norman rule at the time, in buildings like Canterbury Cathedral and Westminster Abbey.

Only centuries later was it misleadingly dubbed “Gothic” by an Italian art historian, the same person who coined the term “Renaissance.” In Spain, it was called the “Gothic of the Catholic Kings.” Eurocentrism at work again.

From Spain to North America

In North America, it is easy to forget that when the Spanish arrived in Mexico in 1492, they came from a world in which Christians and Muslims had shared rule for nearly 800 years. The Spanish colonizers did not build in the style of the native Americans whose lands they took, but imported the styles of their homeland, just as the Umayyads had recreated the Syrian styles of their homeland in Spain, modelling the Cordoba Mezquita on the Damascus Umayyad Mosque. The influence of “the Moors,” as the Muslims were known, can be found in practically every style of Spain from the 8th century onwards, with its unmistakable tinge of Orientalism.

The Spanish missions in California and Arizona, founded by Catholic priests of the Franciscan order in the 18th and 19th centuries, also imported the styles of their homeland, and Moorish designs are evident in San Xavier del Bac and San Luis Rey de Francia.

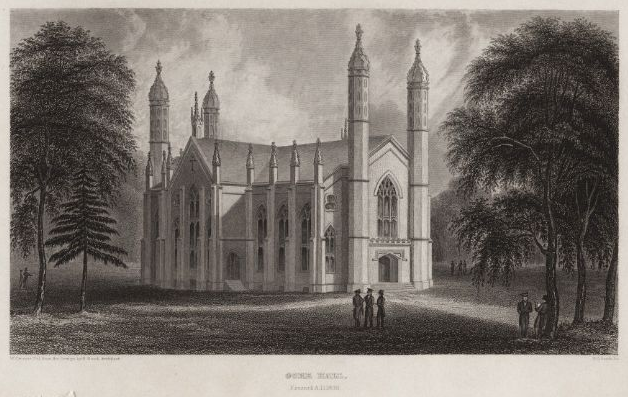

Taking inspiration from English Oxford and Cambridge colleges, “Collegiate Gothic,” as it is known, began in 19th century America with church-like libraries at prestigious universities such as Harvard’s Gore Hall.

The popularity of Collegiate Gothic endures into the 21st century, with prominent “new” buildings still seen as representing the pinnacle of sophistication, such as Yale’s Benjamin Franklin College and Princeton’s Whitman College. Much of Yale’s campus can be considered “Gothic,” including Yale Law School.

In Europe too there is still one famous neo-Gothic church under construction. Its Spanish architect, Antoni Gaudí, another devout Catholic, openly acknowledged the influence of Islamic architecture in his masterpiece, the Sagrada Família in Barcelona. It is a style we might call Hispano-Saracenic-Gothic, representing the ultimate fusion of nature, geometry, and religion. A multinational team is collaborating to complete it in time for the 2026 centenary of Gaudí’s death, using materials from all over the world.

On top of all the “Saracen,” “Moorish” elements we have identified in so-called “Gothic” buildings, there is still one more surprising thing to take in: The Capitol building in Washington, DC owes a debt to Islamic architecture, through its double dome.

This is the technique, first used in Seljuk tombs and later Ottoman mosques by the great court architect Sinan, where the exterior profile is taller, in order to make a bold silhouette on the skyline, than the interior dome, which is lower, with a hollow space in between. The clever device was copied across Europe, notably by Wren in his iconic dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London where he openly admitted use of what he called “Saracen vaulting.” That is why the cover of this beautifully illustrated book shows the interior dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Surely if there is a lesson in all of this, it is that no one “owns” architecture, just as no one “owns” science. Everything builds on everything else.

How wonderful it would be, in this current age of Islamophobia and nationalism, if we could acknowledge the ties that bind us, often in mysterious and unseen ways, rather than seeking to airbrush them out of our history. My hope is that an enhanced understanding of the shared elements of Christian and Islamic architecture might encourage us toward a broader inter-religious dialogue, even with those we may sometimes have seen as “the enemy.”

Diana Darke is a non-resident scholar with MEI's Syria Program and an independent Middle East cultural expert and Syria specialist. She is the author of My House in Damascus: An Inside View of the Syrian Crisis (2016), The Merchant of Syria (2018), and, most recently, Stealing from the Saracens: How Islamic Architecture Shaped Europe (2020), on which this piece is based. The views expressed in this article are her own.

Main photo: View of St. Paul's Cathedral interior dome. (Diliff, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.