The broader Middle East’s role and relevance in that global context continues to shift. During the past quarter century, successive United States administrations have tried to articulate and advance policies that sought to proactively change dynamics in the region through diplomacy, military action, and other forms of engagement, all with limited success and outcomes that did not measure up to the aspirations and goals set.

This report provides an interim assessment of the Biden administration’s overall Middle East strategy and examines the strategic opportunities and risks for U.S. policy in the broader region. This is the first in a series of reports to be released quarterly on U.S. policy in the Middle East.

Introduction and Executive Summary

Today’s international system is unlike the one that emerged in 1991, after the end of the Cold War. The broader Middle East’s role and relevance in that global context continues to shift. During the past quarter century, successive United States administrations have tried to articulate and advance policies that sought to proactively change dynamics in the region through diplomacy, military action, and other forms of engagement, all with limited success and outcomes that did not measure up to the aspirations and goals set.

The past three administrations have sought to limit America’s engagement after several years of post-9/11 deeper U.S. involvement in the region, and the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations have all seen limited outcomes from that approach. As the Biden administration nears the end of its third year in office, this assessment identifies three distinct phases in its overall strategy in the Middle East:

- Attempted Rebalance: January 2021 to June 2022

- Limited Strategic Re-engagement: July 2022 to April 2023

- Reaching for a More Proactive Strategy: May 2023 to September 2023

Examining the current landscape and looking ahead to the coming year and beyond, the United States faces three opportunities and three risks in its overall Middle East strategy.

Opportunities:

- Regional integration that enhances the broader Middle East’s value in the evolving global landscape and strengthens overall security and prosperity.

- Improved security and economic conditions help address the endemic human security challenges that generate problems in the Middle East and surrounding regions.

- A clearer pathway toward a “new normal” in America’s relationship with the region.

Risks:

- Threats generated from within the region, including state failure, ongoing civil wars, attacks by terrorist networks, and risk of wider escalation.

- Risks the region becomes an arena for geopolitical conflict and destructive competition.

- Hyper-partisanship within America’s political system harms a steadier policy approach.

This report provides an interim assessment of the Biden administration’s overall Middle East strategy and examines the strategic opportunities and risks for U.S. policy in the broader region. This is the first in a series of reports to be released quarterly on U.S. policy in the Middle East.

Phase One: Attempted Rebalance, January 2021-June 2022

Unlike his recent predecessors, President Joe Biden did not place a high priority on the Middle East in his overall foreign policy. He entered office in January 2021, at a time when the top issues that propelled him into the White House consisted of anything but the broader Middle East.

The center of gravity in his early days was focused on an unprecedented crisis at home, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic that was killing 4,000 people a day in America and a forced shutdown of the economy that put more than 10 million Americans out of work. In the world, Biden prioritized efforts to re-engage allies and partners in Asia and Europe, respond to the rise of China, and tackle climate change. His first trip overseas as president was to Europe, where he met North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies and held a summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Switzerland.

Trying to Turn the Page on the Middle East, Again

Some Biden administration officials in the first year stated that they were trying to move U.S. policy “back to basics” — meaning they wanted to transcend the habit of previous administrations to overpromise and underdeliver in the region. This initial approach was criticized from many different angles in the U.S. policy debate, with some saying the Biden team was doing too little, while others objected that it was still doing too much. One outside observer summed up the early Biden approach to the Middle East as one of “ruthless pragmatism.”

One example of this was the Biden administration’s passive approach to Syria, which continued to represent a source of instability for the broader state system in the Middle East. The Biden team nominally conducted a policy review on Syria, but it did little beyond efforts to keep cross-border aid into northwest Syria from Turkey open. It stood back while countries in the region like Jordan and the United Arab Emirates began to engage Bashar al-Assad’s regime and start a process of normalization.

Iraq represents another example of the Biden administration seeking to maintain limits on how much it directly engaged with the challenges, particularly compared to its recent history. As Iraq faced multiple human security predicaments and political turmoil during the first part of the Biden administration, the United States maintained a more distanced diplomatic posture, although it kept its limited troop presence to provide support to Iraq’s security forces.

The fundamentals included sticking to more modest goals, putting an emphasis on limited diplomacy, and safeguarding against becoming overextended in the region. This new approach was more cautious than the Trump’s administration’s efforts in the Middle East, which took risks in its policies on Iran and sent decidedly mixed signals about America’s overall posture in the region. The Trump administration had focused on the military defeat of the Islamic State, the “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran, and efforts to forge normalization agreements between Israel and Arab states, including the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan.

By contrast, the Biden administration’s initial stance was to guard against the deep levels of engagement that had at times overwhelmed the broader agendas of the past three U.S. administrations. In its first year, it appointed special envoys on Yemen, Libya, and the Horn of Africa (while at the same time eliminating the position of Syria envoy and downgrading its diplomatic engagement on the country), and it reengaged Iran in international talks on its nuclear program in Vienna. The Biden team also indicated it would seek to lean on regional partners more heavily than in the past.

The Middle East received scant mention in Biden’s March 2021 Interim National Security Guidance, though it dutifully checked the boxes on reasserting America’s “ironclad” commitment to Israel’s security as well as efforts to deter Iranian aggression and disrupt the Islamic State. The document additionally expressed a general desire to “de-escalate” tensions in the Middle East and stated that the United States would not give Middle Eastern partners a “blank check” to pursue policies at odds with America’s interests and values. Furthermore, it expressed a general goal of “right-sizing” the U.S. military presence in the region.

Biden’s overall message to the world in his first foreign policy speech as president, delivered at the State Department just weeks into office, was “America is back,” but here too the Middle East did not get much attention compared to other global concerns. In the early weeks of the Biden administration, its priorities in the Middle East consisted of diplomatic efforts to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal as well as a stated goal to recalibrate ties with Saudi Arabia (the first of several episodes in that rocky bilateral relationship) and de-escalate regional conflicts.

Biden announced the appointment of a special envoy to step up U.S. diplomacy in an effort to end the war in Yemen as well as an end to U.S. support for “offensive” operations in the war, including relevant arms sales, even if the definition of what that actually meant in practice was unclear. In one of its early moves on Yemen, it de-listed the Houthi movement as a terrorist organization, the initial effect of which may have undercut the stated goal of achieving a diplomatic resolution to the conflict.

The Biden administration also tread cautiously on Israeli-Palestinian issues. It announced some $388.5 million in aid to the Palestinians, including the resumption of funding cuts by the previous administration, including support for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), as well as economic and humanitarian assistance. But Israel’s ongoing political turmoil, involving five elections in three years, clouded the vision for a new pathway on the Israeli-Palestinian front, as did turmoil and division among Palestinians.

The May 2021 conflict between Israel and Hamas drew the United States more directly into the Israeli-Palestinian issue than the Biden administration had initially planned. The crisis that erupted in May prompted the United States to work with key regional actors such as Egypt and take practical measures to end the conflict. But even as it engaged in this diplomacy, the Biden team tried to limit the amount of time that senior-level officials spent on this because the focus remained on the president’s trip to Europe in June 2021.

Reverberations From the Afghanistan Pullout in August 2021

America’s military withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 marked the end of an era in U.S. foreign policy, and it also made a distinct impression among adversaries and partners in the region and around the world.

The benefits of America’s departure were that it freed up some military and intelligence resources for the broader competition against Russia and China. It also helped shift America’s national attention beyond the post-9/11 period that dominated U.S. foreign policy for two decades. But those benefits were frequently overstated by the Biden administration, with the decision to leave presented as a false choice between getting out immediately or being forced to ramp up the U.S. military presence with no end in sight.

By the end of its 20 years in Afghanistan, the number of U.S. troops on the ground, its direct involvement, and the associated costs were much more limited compared to the period after the Obama administration’s surge in 2010. In mid-2023, the United States had about 30,000 troops on the ground in the broader Middle East, sharply down from around a dozen years ago, when the United States had more than a quarter of a million troops there, mostly due to the concurrent military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. These figures are not precise because of the use of private military contractors and other factors, but the overall trajectory has been downward in terms of America’s troop presence in the broader Middle East over the last decade.

The strategic costs of how the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan are substantial: America’s competitors have cited the haphazard manner of its withdrawal as another sign of American decline in the world. The betrayal of tens of thousands of Afghans affiliated with the U.S. campaign who were left behind and remain at risk is seen by some as a sign that America doesn’t stand by its partners. Most Americans have looked on in embarrassed silence at the backsliding on basic freedoms and human rights in Afghanistan, and events over the past year have undercut the theme of “democracies versus autocracies” that the Biden administration has tried to use to frame its overall foreign policy. The harsh treatment of women and religious minorities under Taliban rule undermined the message the Biden team tried to send in organizing the “Summit for Democracy” in December 2021 and a follow-up one in March 2023.

The withdrawal also marked a turning point in President Biden’s first year in office, with his public approval ratings among voters in the United States dropping substantially in part because of the images of America’s chaotic withdrawal and the human costs associated with how it was implemented. Biden had promised the process would be orderly, yet it turned out to be anything but that. This damaged the brand the administration had developed for itself, as more competent than its predecessor. The mishandling of Afghanistan coincided with the stalling of Biden’s domestic policy agenda, amid growing concerns about COVID-19 variants, inflation, and other economic woes.

The Start of Some Tactical Adjustments

After the Biden team did not get the results it had hoped for with its initial approach to the region, it started to face some tough realities and began making tactical adjustments. Coming to a new agreement with Iran to rejoin the 2015 nuclear deal proved difficult because of the shifts in power in Tehran and the ongoing regional instability backed by Iran. The conflict in Yemen continued, but so did stepped-up diplomacy. The Israeli-Palestinian issue remained stalemated and a low priority for the Biden team, even as conditions on the ground deteriorated.

The common thread between the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations — the desire to limit U.S. involvement in the Middle East — made the biggest impression on the region. The initial Biden administration posture, thus, incentivized strategic hedging among key countries in the region, which have consequently worked to forge deeper ties with other outside actors, especially China, Russia, India, and some European countries. It also created incentives for many regional states to adopt a more assertive, “go your own way” approach.

In the face of these setbacks on the broader Middle East agenda, some on the team began to see the risk of the initial approach: that it put the United States in reactive mode strategically, beholden to events instead of seeking to proactively shape trends through diplomacy and other forms of engagement.

As a result, the Biden team during this first phase began to plant the seeds for a more proactive strategy in the region with some moves toward the start of its second year in office. In March 2022, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken participated in the Negev Summit, a meeting that brought together four Arab foreign ministers with Israel’s foreign minister to discuss ways to build on the regional normalization and integration trends set into motion by the 2020 Abraham Accords as well as consider practical cooperation on human security issues. Blinken took part in this forum after a series of meetings with Palestinian leaders, including Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, and civil society, but the Palestinians remained outside of the process.

Phase Two: Limited Strategic Re-Engagement, July 2022-April 2023

President Biden’s trip to the Middle East on July 13-16, 2022, represented an important shift in the still-new administration’s strategy toward the region. The prime motivator for this shift was driven largely by external factors, namely Russia’s war and invasion of Ukraine driving up global energy and food prices. These higher prices had an impact on Biden’s standing at home, as concerns about inflation shot to the top of the political agenda ahead of the midterm elections.

This external factor, combined with the lack of clear outcomes from his administration’s initial approach to the Middle East itself, took Biden to Israel and Saudi Arabia in the second summer of his presidency, and that trip, along with other diplomatic and military moves, spawned several other initiatives that are still playing out in Biden’s evolving Middle East policy.

A key objective for this trip was to send a signal that the United States remains committed to the region at a time of geopolitical uncertainty when other outside actors, particularly Russia and China, are working in their own ways to impact trends across the region. Despite years of talk about America’s increasing energy independence and the shift to a green energy economy, the realization that such a transition would take a much longer time, combined with the shock of geopolitical instability from Russia’s war against Ukraine, served as a reminder that the broader Middle East remained vital to the global economy and energy market. This prompted Biden to send a direct message to the leaders of key countries in the region that was at odds with much of what Presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama said. In a speech on the final day (a Saturday) of his visit to the region, Biden declared:

Let me state clearly that the United States is going to remain an active, engaged partner in the Middle East. As the world grows more competitive and the challenges we face more complex, it is only becoming clearer to me […] how closely interwoven America’s interests are with the successes of the Middle East. We will not walk away and leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Russia, or Iran. And we’ll seek to build on this moment with active, principled American leadership.

The trip offered an opportunity to shift the framework for U.S. policy in the Middle East away from the post-9/11 militarization toward a new type of engagement that seeks to build partnerships and helps foster trends in the direction of de-escalation and greater regional integration.

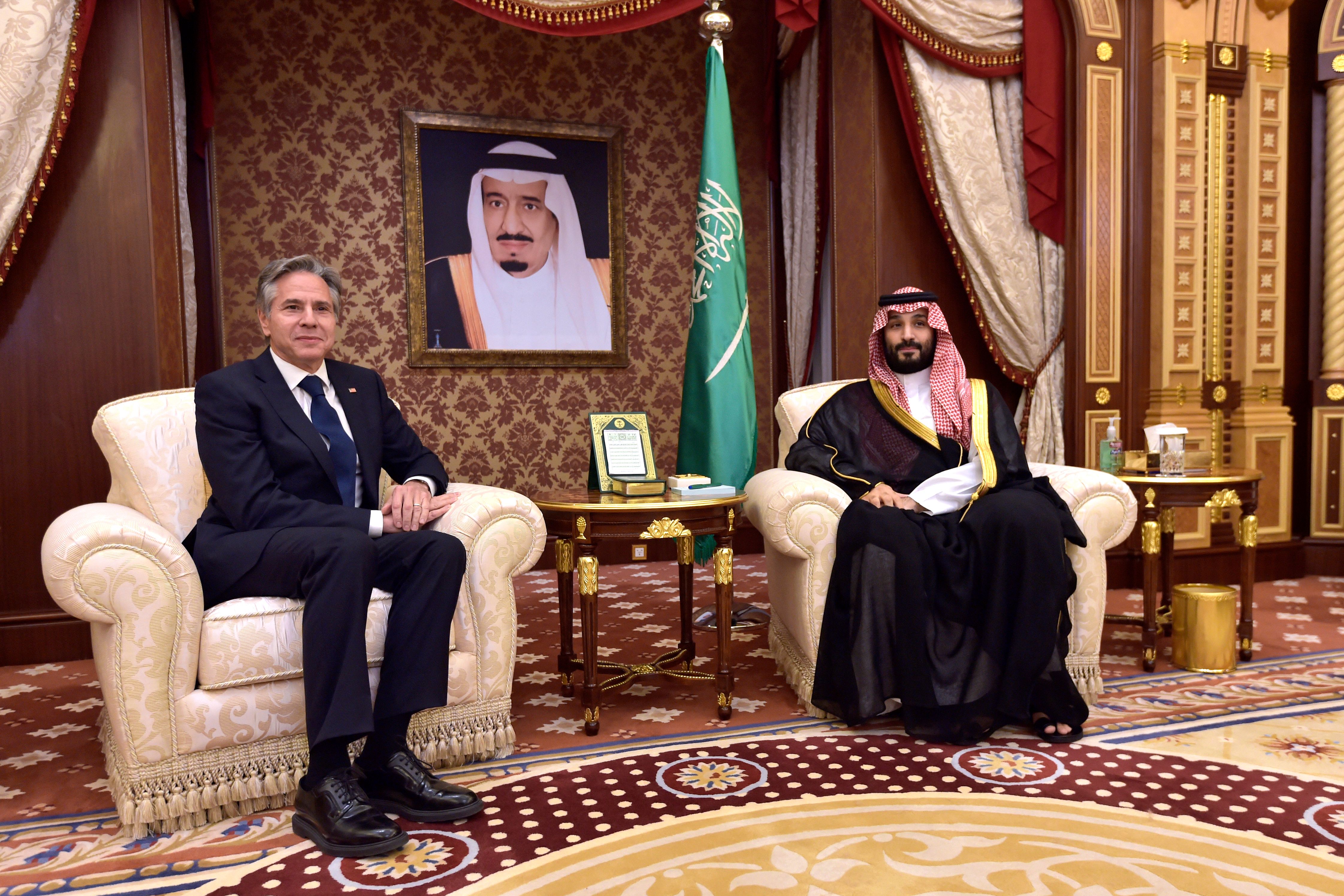

Although many observers will likely remember the trip for the image of Biden’s “fist bump” with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the meetings in both Israel and Saudi Arabia ended up producing a rich and detailed policy framework that was mostly under-analyzed by the policy community. The United States signed bilateral framework agreements with both Israel and Saudi Arabia that mapped out cooperation in a wide range of areas, including technology, climate change, and economic cooperation, among other fields. The engagements with Palestinians, however, were much more limited. These moves to deepen ties with two regional powers, Israel and Saudi Arabia, represented something fundamentally different and quite opposite from the restraint or pullback from the region some in America’s domestic politics called for, and it marked an important departure in the Biden administration’s own approach to the broader Middle East.

The Biden visit ushered in a new phase of U.S. engagement in the region, though some of the dynamics and issues were set into motion long before he came into office. This second phase of Biden’s Middle East approach had six key elements to it beyond the president’s trip:

1. A Shift in Focus Toward an “à la Carte” Mini-Lateral and Multilateral Diplomacy

In addition to the bilateral frameworks developed with Israel and Saudi Arabia during Biden’s summer 2022 visit, the United States engaged in a number of diplomatic efforts and created several new forums to address transregional challenges and opportunities. These include:

-

I2U2 — An initiative that brought together Israel, India, the United States, and the UAE and created a framework for promoting joint investments and new initiatives in water, energy, transportation, space, and health and food security. The idea for this was initially generated in an earlier period, but the Biden visit was used to spotlight and elevate it.

-

Bilateral U.S. Partnerships for Accelerating Clean Energy with Saudi Arabia and the UAE followed in July and November 2022, respectively, aimed at coordinating investments in the global energy transition.

-

The October 2022 Israel-Lebanon maritime deal was also the product of important U.S.-led regional diplomacy. Like I2U2, this deal was the result of years of work starting with the Obama administration that continued during the Trump administration. While the Biden administration envoy approached the negotiations differently than his predecessors, much of the content of the agreement was already addressed in past negotiations.

-

Biden’s November 2022 visit to speak at the U.N. Climate Change Conference in Sharm el-Sheikh and meet with Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi was another example of top-level U.S. diplomatic engagement in the region.

-

The Negev Forum working group meeting organized in January 2023 in the UAE was touted by a senior Biden official as “the largest gathering of Arab and Israeli officials since the Madrid process” in the 1990s. The effort seeks to promote regional integration in several important areas, such as regional security, education and tolerance, water and food security, tourism, and energy.

These frameworks present an opportunity for America to shift its focus away from a heavy emphasis on military cooperation and diversify its engagement with the region.

2. An Increased Military Response and Engagement to Security Threats in the Region

The Biden administration entered office signaling its intent to rebalance America’s military posture in the Central Command (CENTCOM) area of operations. The most significant move the administration made there was a complete troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, an effort that came with major complications. In addition, the Biden administration initially repositioned military assets and equipment from key parts of the Middle East. The Russo-Ukrainian war and heightened threats against Taiwan from China also strained the strategic focus and resources available in the Middle East. A global posture review put more emphasis on other parts of the world, and CENTCOM commanders sought to continue the approach of trying to support greater regional integration among America’s Middle Eastern military partners.

Even as the administration sought to rebalance its military approach to the Middle East in the first year, it continued to conduct military strikes against adversaries threatening U.S. troops and partner countries across the region, including strikes that degraded the continued threats posed by the Islamic State and Iranian-backed militias in Iraq and Syria.

By 2022, the U.S. military saw in the changing threat landscape the need to increase its posture through joint exercises designed to send a message to adversaries like Iran and its networks across the region. These included joint military exercises between the United States, Israel, the UAE, and Bahrain in the Red Sea; ongoing operations in the Gulf; and a joint air military exercise over maritime chokepoints in the region that may be a preview of coming efforts aimed at sending a message to Iran about its destabilizing regional activities. Furthermore, the biggest-ever U.S.-Israel military exercise was held in January 2023. Later that same year, the United States and Saudi Arabia conducted Red Sands training exercises and once again held Bright Star in Egypt with 34 participating countries — the oldest multinational military exercise in the Middle East and Africa. These moves highlighted the goal of advancing greater regional security integration and military interoperability, and it demonstrated how the United States remained committed to staying engaged in the Middle East, even as it drew down the number of troops stationed in the broader region.

In early 2023, a U.S. interagency team was in Saudi Arabia for a series of working group meetings with Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members to discuss ongoing regional cooperation. The Pentagon’s principal official for the Middle East, Deputy Assistant Secretary Dana Stroul, pointed out the extensive U.S. defense and security cooperation that the Biden administration has maintained, despite challenges like Russia’s war against Ukraine and China dominating its attention.

3. The Collapse of Biden’s “Plan A” Policy on Iran Without the Development of a “Plan B”

The Biden administration came into office seeking to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal but found that “Plan A” did not work out the way it had hoped. The Biden team spoke of bringing Iran’s nuclear program “into a box” through diplomacy. Indirect talks to revive the nuclear deal began in April 2021 but produced no clear results. In the earlier part of Biden’s term, some officials asserted that they were using diplomacy to deliver a “longer and stronger” deal, one that was better than the original 2015 nuclear deal. Such a deal remains illusory, even as certain provisions of the original agreement are set to expire soon, and Iran continues to maintain a nuclear enrichment program that is beyond what is needed for civilian nuclear energy.

No clear “Plan B” has been crafted. Instead, America’s Iran policy suffers from strategic drift, with no coherent and effective U.S. policy responses on key issues such as what to do about Iran’s continued repression of its people, the regime’s ongoing nuclear efforts, actions that destabilize regional security, and stepped up Iranian-Russian military cooperation, including on drone warfare.

In this period and later in 2023, a steady stream of security incidents between Iran and its network of proxies throughout the region targeted America and several of its partners. Most recently, these episodes have included Iran-backed militia attacks against the U.S. military in Syria. In addition, renewed clashes between Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Gaza and Israel threatened to undercut overall stability in the region. Along with these negative security dynamics, political tensions within some countries, such as Iraq and Lebanon, have links to the broader competition for power and influence between Iran and its neighbors. The United States deployed additional F-35 and F-16 jets and warships to the region to safeguard against further threats.

The Biden administration tried to keep the Iran nuclear talks compartmentalized from regional security and geopolitical dynamics, but it has not seen much success. It implemented a prisoner exchange that included giving Iran access to $6 billion in frozen funds in September 2023, but this did not appear to offer many signs of other diplomatic openings on other issues of concern.

4. Additional Turbulence With Saudi Arabia in the Fall of 2022

The October 2022 decision by OPEC+ to cut oil production by 2 million barrels per day sparked a political firestorm in the United States. Representing the biggest cut in oil production since the start of the pandemic, the move was strongly criticized by the Biden administration and a chorus of voices in Congress. “There will be consequences,” President Biden warned when asked about the decision, and he reportedly ordered a policy review to examine options, calling to mind the stated goal of a “recalibration” in U.S.-Saudi bilateral ties voiced in the first year that didn’t appear to materialize. Some prominent senators reacted by calling for a freeze on U.S. cooperation with Saudi Arabia, including arms sales. The timing of the OPEC+ decision also shifted attention away from Iran just as it was increasing its military cooperation with Russia by providing drones for use in the Ukraine war.

5. Crisis Management Diplomacy on the Israeli-Palestinian Front

The early weeks of 2023 demonstrated how short-term crises and tensions can easily overtake any proactive agenda Washington might seek to set in its foreign policy and push it toward a reactive, crisis-management mode. Quick visits by U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director William Burns, and Secretary of State Blinken to Israel in the opening weeks of 2023 were focused on tensions on the Iranian and Israeli-Palestinian fronts. The formation of the most right-wing government in Israel’s history, with figures in leadership positions who reject a two-state solution, also added to the need for short-term, crisis-management diplomacy that included spring 2023 meetings in Sharm el-Sheikh and Aqaba aimed at lowering tensions between Israelis and Palestinians.

6. Broader De-Escalation Efforts Ongoing in the Region

At the same time these negative security trends were playing out, several key regional actors took positive steps to open up new lines of diplomatic communication: Kuwait and the UAE agreed to return their ambassadors to Tehran after a six-year absence, and Saudi Arabia and Iran held a series of meetings that led to the re-establishment of diplomatic relations and additional talks between key officials. These moves to de-escalate tensions in the Gulf were part of a countervailing trend to the tensions across the region.

Part of this trend in de-escalation included efforts within the region to bridge divides, such as the ending of the boycott of Qatar and the lowering of tensions between Egypt and Turkey, two major countries in the Middle East. The Biden administration adopted a largely hands-off approach with Egypt and Turkey — it engaged both on issues of mutual concern, but it did not place democracy and human rights as a high priority in the agenda. Regarding Turkey, Biden broke with his predecessors and, during his first year in office, recognized the mass killings of Armenians a century ago as a genocide. He also did not visit Turkey or host the Turkish president at the White House, indicating a certain distancing in the relationship. Nevertheless, the Biden administration worked extensively to shape Turkey’s policies in dealing with the fallout from Russia’s war against Ukraine, and it adopted a “wait and see” approach in advance of Turkey’s May 2023 presidential elections.

Efforts by some key countries in the region to promote de-escalation with the Assad regime in Syria through normalization have failed to achieve tangible results. The Biden administration adopted a passive approach to these moves, despite U.S. policies and sanctions aimed at isolating the Assad regime. Syria’s internal situation has continued to deteriorate, and the negative externalities for the region, including a continued flow of drugs like Captagon, continue to undermine regional security. In addition, the long-term presence of millions of Syrian refugees in neighboring countries has presented a major challenge for the host governments.

The Iranian-Saudi agreement announced by China in March 2023 was a prime example of this de-escalation trend. The agreement itself did not appear to yield a markedly improved regional security environment, and threat perceptions about Iran in Saudi Arabia as well as the UAE and Bahrain remained heightened given Iran’s record of conducting attacks using missiles, drones, and cyberattacks. It also did not appear to create a new diplomatic channel to address Iran’s nuclear program.

Phase Three: Reaching for a More Proactive Strategy, May 2023 to Present

If Russia’s war against Ukraine was one of the prime motivators for jumpstarting the Biden administration’s limited strategic re-engagement in its second year in office, the realization that China was moving to make inroads in the region sparked a new level of diplomatic activity by the Biden administration in the Middle East in mid-2023. The fact that China played such a visible role in finalizing and announcing the March 2023 Iran-Saudi Arabia normalization agreement served as a wake-up call for the Biden administration, which had placed rivalry with China high on its broader foreign policy agenda for the whole world.

A cornerstone of the Biden administration’s foreign policy was aimed at connecting the steps to promote a post-pandemic domestic economic revival with some measures to build partnerships and networks of relationships around the world on key issues like infrastructure, clean energy, and technology investments. One of the Biden administration’s main accomplishments in its first term involved passing a set of domestic policy measures, including the spring 2021 economic stimulus bill, the fall 2021 infrastructure investment legislation, and major spending bills to invest in America’s capacity to produce microchips as well as new clean energy infrastructure, which sparked additional private-sector investment. This package helped the U.S. bounce back more strongly than other leading economies after the pandemic, and the Biden team worked to devise new partnerships around the world to compete with China’s ambitious economic engagement strategies, including its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Expanded Economic Statecraft Diplomacy in the Middle East

In the spring of 2023, National Security Advisor Sullivan traveled to Saudi Arabia for a meeting on regional integration with Saudi Prime Minister and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his counterparts from India and the UAE. The officials discussed joint investments in infrastructure projects, including railroads and ports across the region.

This effort on transit infrastructure has clear geopolitical undertones. Both the U.S. and India hope to develop new east-west transit corridors linking South Asia, the Middle East, and Southeastern Europe that will rival China’s much-hyped BRI multi-modal projects. These ideas are linked to previous discussions about the I2U2 initiative, announced during Biden’s July 2022 visit, a concept for joint investments and new initiatives in water, energy, transportation, space, health, and food security involving Israel, India, the UAE, and the U.S.

Like the long-term infrastructure projects for the region under discussion, current U.S. engagement in the Middle East is in the very early stages of trying to build something lasting that generates value and addresses pressing human security needs through partnerships and long-term investments. Sullivan explained the rationale in a May 4 speech, saying, “Every day, we are plugging away at proactive and creative diplomacy across the Middle East region.” His remarks were yet another sign that the Biden administration is staying engaged in the Middle East and sees it as a key region for advancing the United States’ interests and values.

In June, U.S. Secretary of State Blinken traveled to Saudi Arabia, a visit that focused on two main events, a U.S.-GCC ministerial and a meeting of the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Arabian Peninsula Affairs Daniel Benaim offered some insights about this particular trip, articulating a clear strategic rationale for continued U.S. engagement with Saudi Arabia, reiterating a theme of President Biden’s message on his visit to Jeddah last summer: “We will not leave a vacuum for our strategic competitors in the region.”

This mini-burst of diplomacy all culminated in the announcement of a new, ambitious transregional infrastructure project at the G20 summit hosted by India in September 2023. Named the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, or IMEC, it represents a new commitment by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, India, the European Union, Italy, Germany, and the United States to work together to create an interconnected network of railways and ports to facilitate trade, expand access to clean energy, and enhance secure and stable digital connectivity across the region.

Adding More Diplomatic Capacity to the Middle East Team

In the summer of 2023, Secretary of State Blinken named former U.S. Ambassador to Israel Daniel Shapiro as a senior advisor for regional integration, a positive sign that Foggy Bottom and the Biden administration more broadly are looking to make U.S. diplomatic engagement in the Middle East a higher priority. Shapiro is tasked with helping organize efforts to advance the Negev Forum, a regional cooperation framework that brought together the foreign ministers of Egypt, the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, Israel, and the United States in March 2022 to discuss ways to extend the benefits of the 2020 Abraham Accords to a wider circle of people and countries.

This move, along with finally getting career U.S. diplomats in place in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Jordan after some delay, helps position the United States to advance a more proactive regional diplomatic strategy.

Diplomacy on a Possible Saudi-Israel Normalization Deal

In the summer of 2023, news emerged that the Biden administration was engaged in diplomatic efforts to advance a possible normalization deal between Saudi Arabia and Israel. The contours of such a deal likely include separate bilateral defense and security pacts between the United States and Israel and Saudi Arabia; a Saudi-U.S. civilian nuclear agreement and set of deals on economic and technological cooperation that build upon what the two countries laid out after Biden’s visit to the kingdom in the summer of 2022; and some forms of commitments involving the Palestinians, understandings that are currently under discussion and to be determined.

An Israeli-Saudi deal would also be a major accomplishment for regional security and the global economy. But achieving such a deal is a complicated venture given the multiple factors involved.

A Look Ahead: Opportunities and Risks for US Strategy in the Middle East

Examining the current landscape and looking ahead to the coming year and beyond, the United States faces three opportunities and three risks in its overall Middle East strategy.

Opportunities

1. Regional integration that enhances the broader Middle East’s value in the evolving global landscape and strengthens overall security and prosperity. For decades, many Western nations have viewed the Middle East as an “arc of crisis” that did little more than export problems and security threats. This remains true in America, where, after 20 years of costly post-9/11 wars, the region is seen as offering more risks and costs than opportunities and gains. Nevertheless, silver linings exist in an otherwise bleak regional landscape to promote greater interlinkages on the shared economic, energy, water security, and climate change concerns across the region.

Add to that the trillions of dollars of capital from recent energy windfalls that key actors in the region are seeking to deploy in new and different ways, along with efforts to advance regional integration and normalization and get ahead of challenges like climate change by promoting a pragmatic energy transition, and there are opportunities to pursue. The fact that several countries with these resources have put forward long-term economic and social transformation projects, like the Saudi Vision 2030, is a sign that perhaps something is changing in the region. The recent normalization accords in the Middle East represent an important step forward, even though those deals won’t likely deepen or expand to other countries without meaningful progress that includes the Palestinians. A careful look at the region sees important opportunities to address some of the many human security challenges in a collaborative way.

2. Improved security and economic conditions help address the endemic human security challenges that generate problems in the Middle East and surrounding regions. The recent devastation in Morocco and Libya from natural disasters exposed once again how fragile many countries in the broader Middle East are. Yet the Biden administration’s shift toward more diplomacy and economic statecraft measures in its Middle East policy could open the door to new ways to address such endemic regional human security challenges as high youth unemployment, a lack of sufficient infrastructure, poor human capital development, and underinvestment in the education and health sectors. The old models for political economies of the region have not responded sufficiently to the urgent needs of their societies; but fostering greater regional integration and connectivity might incentivize a new pathway for stronger governance and private sector investment, if widespread corruption and rule of law problems are addressed.

3. A clearer pathway toward a “new normal” in America’s relationship with the region. During the past 40 years, America’s relationship with the region has become increasingly militarized as a result of the multiple conventional and terrorist security threats that have emerged. But the above-mentioned more recent new dynamics offer a chance for the United States to reset its relationship with the region so that it can address challenges at home and focus on other foreign policy priorities. By investing in more diplomacy in the region, the United States has a better chance of right-sizing its presence and encouraging more stable relationships based on mutual respect.

Risks

1. Threats generated from within the region, including state failure, ongoing civil wars, attacks by terrorist networks, and risk of wider escalation. The threats and challenges posed by the broader Middle East are well known; the news media and much of the think tank community are fixated on these problems, leaving a policy discourse stuck in the moment without a longer-term, proactive vision. The Islamic Republic of Iran represents a continued strategic risk to stability, despite efforts by countries in the region to build stronger diplomatic ties. The lack of a clear Plan B for U.S. policy on Iran remains one of the biggest weaknesses in Biden’s Middle East approach. In addition, Iran’s regional network of partners as well as terrorist groups like Palestinian Islamic Jihad often undertake actions that divert resources from proactive agendas, as do civil wars and conflicts in places like Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Palestine. Finally, the threat posed by the Islamic State, particularly in parts of northern Syria, has led the Biden administration to maintain a troop presence there, even though the administration has not invested sufficiently in securing conditions more broadly that allow that investment in partnerships to be durable and sustainable. The clock may be ticking on America’s deployment, and the Islamic State stands very likely to benefit if U.S. troops depart, just as was witnessed in Iraq.

The “right-sizing” of America’s military presence in the region, combined with military efforts to produce greater regional integration and interoperability, represents an effort by America to address strains on its resources from demands produced by Russia’s war against Ukraine and China’s security threats to Taiwan. Wider threats of regional wars, though much diminished these days, remain a present danger in parts of the Middle East and the Horn of Africa. CENTCOM’s mission and strategy still contains a long list of threats and priorities, and today it is unclear if the U.S. military has sufficient resources in the broader Middle East to meet the various contingencies and threats.

In addition to hard security threats coming from within the region, the broader Middle East continues to suffer from a massive human freedom deficit, with a broad lack of respect for political rights, civil liberties, and the rule of law, all of which undercut stability. In places like Egypt, Turkey, Iraq, Tunisia, and Lebanon, many of the pressing human security challenges that were a factor in the 2011 Arab uprisings are present today, and the political and social discontent could easily bubble up again into new rounds of protests and instability.

2. Risks the region becomes an arena for geopolitical conflict and destructive competition. The risk that the broader Middle East becomes an arena for geopolitical conflict between the United States and countries like Russia and China is not as high as the risks emanating from threats within the region. But recent incidents between the militaries of the U.S. and Russia in Syria raise a red flag about how conflicts and tensions between outside powers might undercut regional stability and spill over to neighboring regions. In addition, China’s steady stepped-up engagement in key parts of the Middle East presents a possible risk of destructive, zero-sum competition between Beijing and Washington.

3. Hyper-partisanship within America’s political system harms a steadier policy approach. For more than two decades, the divisions and dysfunctions inside of America’s political system have constrained its ability to seize opportunities and address threats in the Middle East as effectively as it could have. As America heads into the 2024 elections, the domestic incentives are strong to engage in destructive debates and undercut a steadier U.S. policy approach to the region.

Conclusion

The United States faces multiple challenges in the world right now, its focus dominated by Russia’s war against Ukraine and China’s threats against Taiwan. But the Middle East remains a key strategic region of the world that also requires U.S. attention.

The Biden administration downgraded the broader Middle East in its first year in office, but then shifted gears in 2022 and stepped up its diplomatic engagement and security support. As it comes closer to the end of its third year in office, it appears poised to embark on an even more ambitious agenda for the region, but it remains unclear if the current administration will have the time, strategic focus, bandwidth, and domestic political consensus to advance a deeper engagement in the Middle East.

For nearly a decade and a half, the debate within the United States about its role in the wider Middle East has swung back and forth, between administrations but also within administrations as well. The Bush administration came into office in 2001 initially focused on other global priorities like China, yet it soon found itself deeply engaged in large and long-term military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. The Obama administration took over vowing to end the war in Iraq, but after it withdrew all U.S. troops at the end of 2011, it found itself sending troops back into Iraq and Syria to combat the threat posed by the Islamic State. The pendulum in the Trump administration’s Middle East approach swung a great deal as well, and a U.S. president who prided himself on his unpredictability sent mixed messages.

The Biden administration’s approach to the region has also evolved substantially in a little more than two and a half years, and it remains to be seen how much it will prioritize the region and build on recent steps toward a broader Middle East re-engagement as it heads into its fourth year in office.

Brian Katulis is a Senior Fellow and Vice President of Policy at the Middle East Institute.

Photo at the top: U.S. President Joe Biden and Gulf leaders attend the Jeddah Security and Development Summit (GCC+3), July 16, 2022. Photo by MANDEL NGAN/POOL/AFP via Getty Images.

Acknowledgements

The paper benefited from comments and suggestions from several MEI colleagues, including Matthew Czekaj, Benjamin Freedman, Nimrod Goren, Charles Lister, Veronica Marcone, Randa Slim, Alistair Taylor, Gönül Tol, Alex Vatanka, and Joseph Zimbler.

Intellectual Independence

The Middle East Institute maintains strict intellectual independence in all of its projects and publications. MEI as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular issues, nor does it accept funding that seeks to influence the opinions or conclusions of its scholars. Instead, it serves as a convener and forum for discussion and debate, and it regularly publishes and presents a variety of views. All work produced or published by MEI represents solely the opinions and views of its scholars. The views in this paper are reflective only of the author’s analysis and perspective and do not necessarily represent the views of MEI.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.