- The most important drivers shaping the region in 2023

- A country in crisis, Turkey gears up for pivotal elections

- Iran’s regime faces unprecedented pressure at home and even greater isolation abroad

- Israel's new government raises the likelihood of escalation on multiple fronts

- Dangerous trends portend a difficult year for Palestinians

- Global economic dynamics make for a troubling outlook in 2023

- Will a global economic downturn curtail Saudi foreign policy activism?

- Acute economic pressures and geopolitical posturing in North Africa

- Syria faces new instability amid economic collapse and the rise of a narco-state

- Little prospect for change in fragile states Lebanon and Iraq

- Pakistan is headed for a politically tumultuous year

- A consequential year for climate obligations

- America’s ongoing crises of purpose and focus in the Middle East

The most important drivers shaping the region in 2023

Paul Salem

President and CEO

The various subregions of the Middle East and North Africa will be impacted differently by the trends and developments of 2023.

The war in Ukraine is likely to endure through most of the year. This will keep both energy and food prices high. The former will continue to hit energy importers in the region hard but swell the coffers of energy exporters; high food prices will affect the whole region, yet states with ample financial resources should be able to manage and cushion those stresses, whereas resource-strapped states — as well as fully or partially failed states — will leave their citizens increasingly food insecure. Morocco, as the one of the world’s leading producers and exporters of fertilizer, might see some benefits from that increasingly valuable resource.

Many states in the region were already stretched thin during the COVID-19 pandemic, borrowing and spending money to bolster their public health response as well as to shore up sectors that suffered when tourism came to a near standstill, domestic economic activity slowed due to lockdowns, and exports declined because of a sluggish global economy. In 2023, these states will continue to struggle to finance their debts as global interest rates are likely to remain high; their populations will again confront the impacts of high inflation; and their economies will face the challenges of a global economic outlook that will be stagnant at best, or in recession.

The multiple strains will put serious pressure on the most populous MENA country, Egypt, as well as other economies in the region, including Morocco, Tunisia, Jordan, Turkey, and Iran. Lebanon has already tipped over the economic brink. Iraq will struggle to leverage its resource riches to address the socio-economic and governance needs of its people. The populations in the fully or partially failed states of Yemen and Syria, as well as the millions of refugees throughout the region, will have an extremely trying year.

Some countries, mainly in the Gulf, will likely have a banner year of high revenues and continued rapid progress, while many others across the region will face one of the toughest years on record. This stark contrast in fortunes underscores the urgent need for more regional coordination and pooling of resources. Only such measures can help any more MENA countries from tipping into full or partial state failure and help those on the verge of complete collapse, like Lebanon, from undergoing a final breakdown.

The Russian war on Ukraine, which is largely behind the high energy and food prices felt around the world, looks likely to continue through much of the year. Many key regional players, like Turkey, Israel, and most of the Gulf countries, have remained neutral during the crisis, much to the consternation of the West. But as Moscow and Kyiv and some members of the international community eventually look for ways to end the conflict, including ultimately through negotiation and mediation, these key MENA countries could prove diplomatically useful as they maintain relations with and influence on both sides.

While the Middle East is known for unpredictable surprises, there are at least three arenas that we know, even in January, we must watch closely this year. General elections, including presidential elections, are set to be held in Turkey in May. While President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan still commands a large following, economic crisis and runaway inflation have damaged his brand. The region — and the world — will be watching closely to see if he can salvage his presidency, or whether his two decades of rule over Turkey will come to an end. So far, his strength in the elections comes in large part from the ability to clamp down on opponents and civil society, his monopoly control of the media, and the persistent divisions among his political challengers.

A second major arena to watch is the continuing protests and uprisings in Iran. The Islamic Republic has indeed entered a new — perhaps final — phase of its revolutionary life, as the regime has generally lost legitimacy among the bulk of the new generation, which will determine Iran’s future. Ethnically diverse regions of the country are already becoming increasingly restive, and the situation remains a potential powder keg. The authorities, of course, are able and willing to use extreme force to maintain control and will likely ride out 2023 in a similar fashion as they closed out 2022. But the death of the supreme leader or other unforeseen events could tip the country in an unpredictable direction. Changes in Turkey, Iran, or both would, of course, have tremendous consequences, for the MENA region and the wider world.

The third area of focus must be the situation between Israel and Palestine. While uprisings in the occupied West Bank or deadly clashes with the besieged Gaza Strip are a high risk in any year, the new Israeli government — the most right wing in Israel’s 75-year history — is almost certain to further inflame the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the Occupied Territories, Gaza, and possibly inside Israel as well. The United States, along with countries in the region that have normalized relations with Israel, will need to use their leverage to urge the Israeli government to pursue a less confrontational path, and work with both Israeli and Palestinian leaders to find pathways to de-escalation.

In the longer-term bigger picture, the effects of climate change — in terms of higher temperatures, scarcer water resources, and more unstable rainfall patterns — will continue to impact vulnerable areas and populations across MENA. With the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference (27th Conference of the Parties, COP27) having concluded last year in Egypt, and COP28 due to be convened in the United Arab Emirates in late fall, the region is well placed to marshal local and global attention to help shape and implement an effective MENA climate resilience and energy transition plan.

Follow on Twitter: @paul_salem

Image: Photo by Ameer Al-Mohammedawi/picture alliance via Getty Images

A country in crisis, Turkey gears up for pivotal elections

Howard Eissenstat

Non-Resident Scholar

There is little question that 2023 will be a watershed year for Turkey. It is, at this juncture, a country in crisis. Its relations with its North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies have never been more fragile, its economy is in shambles, and its democratic structures are in tatters. Nonetheless, national elections, scheduled for May 14, 2023, offer at least the sliver of hope that Turkey can pull itself back from the brink.

It would be hard to overstate the importance of these elections. A victory by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its Nationalist Action Party (MHP) allies would allow Erdoğan to further cement his authoritarian rule and further undermine whatever is left of a free press and independent institutions in Turkey. A victory by the opposition would, at a minimum, provide an opportunity for some reconstitution of those institutions and provide greater space for Turkey’s besieged civil society.

The path for the opposition, which despite attempts to unite, has significant fractures and has yet to choose a candidate for the presidency, is far from certain. It does, however, have some advantages: frustration with historically large numbers of migrants is one. The high rate of inflation, spurred in large part by Erdoğan’s idiosyncratic economic theories, is another. At the same time, the opposition must face court systems, electoral officials, and prosecutors who serve the political interests of the president as well as a media system that is almost entirely under the sway of the governing party. They must also surmount their own fractures, particularly between traditional Turkish nationalists and the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). Already, key opposition leaders are either behind bars or facing prosecution; the HDP faces possible closure before the elections are held. Finally, there is the question of how Erdoğan and his supporters, both within and outside of state institutions, would respond to defeat should the opposition succeed. The possibility of election-related unrest, regardless of who wins, is probably higher now than it has been in many decades.

In the event of an opposition victory, a wide range of challenges would present themselves, from taming inflation to depoliticizing a deeply politicized bureaucracy and court system. It would not be easy, particularly since the opposition parties often have little in common beyond their shared disdain for Erdoğan. Nonetheless, on the domestic front, an opposition victory would likely result in more technocratic management of the economy, a reassertion of professional staff within the diplomatic corps, and more open public space for debate. In foreign affairs, tensions over U.S. support for the Syrian Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) and with Greece and Cyprus in the Eastern Mediterranean will likely continue, but, in the short term at least, the new leadership would be anxious to signal to its traditional allies that it is ready to work with them in good faith. U.S.-Turkish relations would likely enjoy something of a honeymoon and the new government would likely move quickly on Finland and Sweden’s NATO membership. Turkey will remain a challenging partner for both the U.S. and Europe, but an opposition victory would offer the chance to mend ties and come back from the brink.

The more likely scenario, however, is that Erdoğan will win another five-year term, helping him to cement his legacy and further undermining already crumbling institutions. Even under these circumstances, however, one might expect a short-term effort at easing tensions, if only to ensure weapon sales (especially the F-16s) and help deliver some reassurance to foreign investors. Nonetheless, the basic trajectory of Turkey under Erdoğan’s leadership, one shaped by saber-rattling diplomacy, brinksmanship, and a desire to break free of Turkey’s reliance on the West, is likely to continue.

Regardless of the outcome of the elections, 2023 is likely to be a pivotal year for Turkey. The stakes could hardly be higher.

Follow on Twitter: @heissenstat

Image: Photo by ADEM ALTAN/AFP via Getty Images

Iran’s regime faces unprecedented pressure at home and even greater isolation abroad

Alex Vatanka

Director of Iran Program and Senior Fellow, Frontier Europe Initiative

The year 2023 is bound to be a tough one for the Islamic Republic. Tehran’s Islamist political model will remain under unprecedented pressure. As the months of unrest in late 2022 made clear, the Iranian public has all but given up on the regime’s willingness to change course on key domestic issues. The record-high brain drain and capital flight will continue as Iranians, plagued by historic levels of inflation and unemployment, rapidly declining purchasing power, and general poor governance, are voting with their feet and leaving.

Not everyone can emigrate, however. More popular unrest is thus very likely as the country’s restless younger generation has a long and growing list of grievances against a political order that has in essence forfeited the national well-being to pursue a highly ideological and costly foreign policy. As a result, Iran has found itself largely alone on the international stage and in economic free-fall as the second-most-sanctioned country in the world after Russia. Meanwhile, an isolated Iran will find it increasingly difficult to tackle some of the most pressing issues it faces, including the severe and steadily worsening impact of climate change.

The master of this failing system, 83-year-old Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, is notoriously obstinate. A man with infinite power to do as he wishes, Khamenei has never during his 34-year reign apologized for anything. In 2023, he will remain determined to stay the course. He will dismiss the domestic protesters as simpletons and agents of the West even as numerous studies produced by his own regime are ringing the alarm bells about a desperate, angry population ready to erupt.

But there are also clear signs that other senior voices in the regime are willing to accept that major changes might be needed to address popular demands. In 2023, lip service may be paid to the idea of political evolution initiated from within the regime. Even so, as long as the unyielding Khamenei is still alive, the most regime insiders advocating for piecemeal reform can do is to prepare the ground for the day he passes from the scene.

On the foreign policy front, the regime’s standoff with the West is unlikely to abate. A failure to reach a new nuclear deal with Washington and its European allies, combined with a ruthless crackdown on the protest movement inside Iran and a military partnership with Russia in the Ukraine war, has created a united transatlantic understanding that Tehran’s policies need to be confronted. What this means in 2023 is that Tehran’s isolation will only deepen, which in turn raises serious doubts about whether the West can reach a new nuclear deal with Iran anytime soon.

Tehran will maintain that it can weather the storm, but its tenacity will be put to the test — repeatedly. Iran may choose to retaliate by escalating tensions. It can target U.S. and European interests in the Middle East — such as by hampering trade between the West and the Gulf states — but in doing so it is likely to further alienate more countries, including neighbors that Tehran has cultivated in recent years as key economic partners.

The year 2023 could also finally put to bed Khamenei’s notion that Russia and China are silver bullets that can offset Western pressure. China has already made it clear that its ties with Iran will not come at an expense of its other interests in the Middle East. And while Vladimir Putin might be Khamenei’s soulmate in wanting to end what both men see as American global hegemony, Russia is hardly in a position to rescue the faltering Iranian economy, which is likely to present the most pressing trial for Khamenei’s regime in 2023.

Follow on Twitter: @AlexVatanka

Image: Photo by Iranian Leader Press Office/Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Israel's new government raises the likelihood of escalation on multiple fronts

Nimrod Goren

Senior Fellow for Israeli Affairs

The new Israeli government is unprecedented in terms of its extremist composition and declared policy intentions. The coming to power of such a government raises the likelihood of escalation on multiple fronts — domestically, with the Palestinians, and regionally. While some degree of escalation may be unavoidable, its sequence and intensity could be shaped by the actions of Israeli and international actors.

Benjamin Netanyahu begins his current term as prime minister with a domestic focus, and with a sense of urgency that relates to a personal, not national, issue. Seeking a way out of his corruption trial seems to be his top priority. This dictated which parties became part of the coalition, and which policy directives are advanced first.

In his first months in office, Netanyahu is likely to promote the judicial reforms announced by Justice Minister Yariv Levin. If approved, these reforms will dramatically undermine Israeli democracy, and that is already generating significant pushback and causing deep polarization within Israel.

Domestic escalation is therefore coming first. It seems to be a price Netanyahu is willing to pay to solve his personal legal problems and consolidate power. While doing so, he will be seeking international legitimacy and regional stability, to give him more room to maneuver domestically and to counter claims that the government damages Israel's global standing. For that reason, Netanyahu may be willing to abide by certain redlines conveyed by the Biden administration (for example, on settlements and Jerusalem).

Things have initially been going Netanyahu's way on the international front. Arab leaders have shown interest in continuing to cooperate with his government, a White House visit is reportedly in the works, and the European Union has expressed a desire to continue the high-level dialogue it launched with former Prime Minister Yair Lapid. While international actors are raising red flags and voicing genuine concerns, many of them are adopting an almost "business-as-usual" approach, waiting to see whether the new government takes actions on the Palestinian issue that will necessitate a response.

Netanyahu's intention was seemingly to make sure that should escalation on the Palestinian front happen, it would only come second. The recent security deterioration, however, indicates that such an escalation is already taking place, even if that was unintended, and might quickly spiral. In any case, Netanyahu remains determined to block any prospect of a future Palestinian state and has handed authorities related to the West Bank to far-right politicians. Netanyahu may limit them somewhat at first — for the sake of avoiding international crises or regional troubles — but eventually they are likely to carry out provocations in Jerusalem and work to deepen and broaden Israeli control over the Palestinian territories. Such developments might lead to further escalation, especially during the sensitive overlap (in April) between Passover and Ramadan.

An Israeli-Palestinian flare-up could be a catalyst for the third type of escalation — the regional one. If this were to happen, Arab and Muslim countries would find it difficult to maintain their current level of relations with Israel. Regional countries are likely to respond in different ways, depending on the nature of the conflict that erupts, while trying to hold onto the benefits of increased ties with Israel.

Netanyahu, cherishing his regional achievements and seeking to expand the Abraham Accords, may utilize an Israeli-Palestinian escalation to shake up his coalition. If escalation occurs after his desired legal reform is approved, and if he can blame his far-right coalition partners for the flare-up, he may seek to replace an extremist party in his government with a centrist one. He will frame it as a step to restore security and safeguard Israel-Arab relations — a framing that security-oriented centrists, seeking to "save Israel," might adhere to.

Considering these potential developments, and in an attempt to shape them for the better, the international community should already put in place de-escalation mechanisms, conceive of preventive and proactive diplomatic steps it can take, and step up its support for those in Israel pushing back against democratic erosion.

Image: Photo by Amir Levy/Getty Images

Dangerous trends portend a difficult year for Palestinians

Khaled Elgindy

Senior Fellow, Director of Program on Palestine and Palestinian-Israeli Affairs

The year 2022 was especially difficult and violent for Palestinians in the Occupied Territories — but it may prove to be only a preview of the dangers to come in 2023.

More than 200 Palestinians, most of them civilians, were killed by Israeli forces and settlers over the course of 2022, including 152 in the West Bank, making it the deadliest year for Palestinians there since the end of the Second Intifada in 2005. Last year also witnessed a sharp rise in Israeli settler terrorist attacks on Palestinians, as well as a spike in attacks on Israelis, including terrorist incidents that killed 16 civilians, while 5 Israeli soldiers were killed in assaults by Palestinian militants. These trends, along with the installation of the new, right-wing Israeli government — the most extreme in Israel’s history — suggest that 2023 is likely to be even worse than 2022, most notably for Palestinians but quite possibly for Israelis as well.

The inclusion into the ruling coalition of Kahanists and other extremist elements, such as Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, both of whom received key government portfolios with jurisdiction in the Occupied Territories, can be expected to aggravate conditions on the ground in several areas. In addition to stepped-up settlement expansion along with evictions and demolitions against Palestinians, which are all but guaranteed in 2023, some potential flashpoints to watch in the coming year include: widening violence in the West Bank and Israel, a move toward de jure annexation of Palestinian territories, and a possible collapse of the Palestinian Authority (PA).

Even as the threat of another explosion in Gaza remains ever-present, we are likely to see an escalation in violence in the West Bank and possibly in Israel as well. Indeed, Israeli violence has increased sharply since the new Netanyahu government took office; more than 30 Palestinians have been killed as of the start of this year, including 11 in one day as a result of the Israeli army’s deadly Jan. 26 raid on the Jenin Refugee Camp. The armed rebellion led by newly formed militant groups such as the Lions’ Den and Jenin Brigades is likely to continue, posing serious security challenges for the Israeli military as well as the PA and its continued security coordination with Israel. So far, the bulk of the violence has been concentrated in the northern West Bank districts of Nablus and Jenin. But as Palestinian deaths and injuries mount, we could see more attacks on Israeli civilians, which, in turn, could lead to a wider and more brutal crackdown by Israeli authorities on the Palestinian population at large.

As de facto annexation through Israel’s ever-expanding settlement enterprise continues apace in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, the new Israeli government also brings a heightened risk of de jure annexation. While we are unlikely to see a formal declaration of seizure of some or all of the Occupied Territories, which would trigger immediate international condemnation, the coalition agreement for the new government allows for a more subtle slide toward de jure annexation by transferring key authorities related to the occupation from the Ministry of Defense to civilian authorities, most notably under Finance Minister Smotrich.

Years of political and institutional stagnation, growing corruption and authoritarianism, and dwindling economic and fiscal prospects have hobbled the PA’s effectiveness and sapped its domestic legitimacy. The latest developments on the ground and in Israeli politics are likely to accelerate these trends, further weakening the PA and possibly speeding up its collapse. While the PA’s economic woes are chronic, due largely to the dramatic decline in international aid over the last decade and Israel’s withholding of billions in tax transfers collected on behalf of Palestinians, for the first time we have Israeli government ministers openly committed to dismantling the PA. Meanwhile, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas’s decision to cut security coordination with Israel in response to the assault on Jenin camp, which is likely to trigger further retaliatory measures by Israel, further throws the PA’s future in doubt.

Follow on Twitter: @elgindy_

Image: Photo by JACK GUEZ/AFP via Getty Images

Global economic dynamics make for a troubling outlook in 2023

Mirette F. Mabrouk

Senior Fellow and Founding Director of the Egypt program

While few people had particularly high hopes for 2022 on the economic front, it still managed to underperform in a major way. Modest expectations of a gradual, if tentative, recovery from the 2021 pandemic-fueled economic fallout were dashed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February. The economic malaise, which ranged from weaker than expected to downright dismal across the globe, has been felt by almost every country, causing socioeconomic and political ripples that have continued to spread into 2023.

Global inflation shot to almost 9% in 2022, nearly doubling from the year before. While it’s forecast to drop to 6.5% this year, the outlook is still deeply unsettling, particularly for low- and middle-income countries, which are feeling the crunch of a global cost-of-living crisis. Nor is relief likely in the near future. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that global growth will continue to plateau, down from an already halved 3.2% in 2022 to 2.7% in 2023. That isn’t quite global recession level, but it is the lowest it has been in almost two decades.

The countries of the Middle East and North Africa were all hit, to varying degrees, in 2022 as the year’s adverse effects continued to crash into each other like a multi-car pile-up. The global slowdown led to decreased access to market financing and supply chain disruptions; the rising costs of energy meant that food, or indeed, anything requiring transportation, shot up in price; and inflation and the resulting cost-of-living increases made life miserable for the majority of the region’s inhabitants. Only the richer Gulf states remained largely sheltered, protected by the same high energy prices that proved so problematic for their neighbors. Not that they were immune though. The global downtown, coupled with the creeping reality of the eventual phasing out of fossil fuels, has meant that Gulf nations have had to be significantly more circumspect with their money, which translated into less, and more tightly controlled, capital flows to other countries — a point underscored by Saudi Finance Minister Mohammed al-Jadaan in his comments at the World Economic Forum in Davos in mid-January 2023.

One of the clearest examples of this new policy can be seen in Egypt, the region’s most populous country. Long one of the largest recipients of Gulf aid and investment, Egypt had just managed to withstand the economic fallout of the pandemic, being the only country in the region to maintain positive growth in 2020. However, 2022’s combined fallout from the pandemic and the war in Ukraine proved too much for an economy badly in need of structural reforms. Inflation shot up to over 20%, its highest ever level, and food prices skyrocketed. Hot money, which always flees developing economies for developed ones in times of crisis, predictably fled the country, slashing into Egypt’s hard currency reserves. These reserves had already been weakened by the rise in import costs linked to the Russo-Ukrainian war and the country’s own expensive mega-projects. After months of negotiations, the IMF agreed on a loan, Egypt’s fourth in six years. The conditions included the flotation (and consequent devaluation) of the Egyptian pound, which is pegged to the U.S. dollar. The resulting devaluation has placed enormous strain on the economy and Egyptian citizens and is likely to represent the government’s most pressing challenge in 2023. The government has scrambled to get its arms around the crisis and many of its measures reflect current global trends. In line with what the IMF called “increasingly synchronized monetary policy around the world,” the Central Bank of Egypt has hiked interest rates. Egypt, however, needs external financing, and the Gulf countries, which had previously stood at the ready to help, have changed their policies. Egypt will now have to court their investment.

That change is reflective of shifting global alliances and geostrategic priorities, a dynamic that will continue to shape the region in 2023. Countries are having to scramble and reassess their relations; even former superpowers should no longer take such relationships for granted.

The war in Ukraine will also have significant, if indirect, consequences for developing economies. Estimating the amount of Western aid to Ukraine can be notoriously difficult, according to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, a German research institute which does precisely that. The U.S. alone has pumped nearly $100 billion into aid for Ukraine. EU figures are similar. Clearly it is impossible to tell whether that money was originally earmarked for other recipients, but it is fair to assume that at least some of it had to be redirected. Developing nations, many of which are reliant on Western aid and financing, are almost certain to be directly impacted. Add to that the fact that global monetary policy has seen a rise in interest rates and reduced market financing and the economic picture looks increasingly bleak for many developing countries in 2023.

However, 2023 watchers will have to contend with more than just monetary policy changes and shifting geostrategic alliances. Climate change wreaked havoc across the globe in 2022 and is likely to do so again this year. Last year, catastrophic flooding cost Pakistan over $40 billion, Europe sweltered to the tune of $10 billion, and climate-change-propelled hurricanes cost the U.S. more than $100 billion. Lower-income nations, which often have neither the money nor the infrastructure to deal with the effects of climate change that they themselves did not cause, will suffer greatly. While the 2022 U.N. Climate Change Conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, resulted in a historic deal on a fund for loss and damage for vulnerable countries, little was accomplished on greenhouse emissions. Considering the fact that most of the countries in the MENA region, with the exception of the Gulf states, are agrarian economies, climate change presents an immediate threat to security and stability.

While the picture looks bleak for many, there might be one silver lining to the looming clouds. Many economies in the region have had urgent structural reforms that their governments have managed to ignore. However, at this stage, given the increased threats to security and stability, governments will no longer be able to avoid the floodwaters lapping at their feet.

Follow on Twitter: @mmabrouk

Image: Photo by Ahmed Gomaa/Xinhua via Getty Images

Will a global economic downturn curtail Saudi foreign policy activism?

Gerald M. Feierstein

Distinguished Sr. Fellow on U.S. Diplomacy; Director, Arabian Peninsula Affairs

Global oil markets have returned to positive growth in recent days as investors see the end of China’s COVID-19 restrictions and renewed Chinese economic expansion driving higher energy demand. In January, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecast a rise in global demand of 1.9 million barrels per day (mbpd) for the year, bringing it to a record 101.7 mbpd. Half of the growth, according to the IEA, will come from China. Nevertheless, questions about the global economy challenged investor sentiment in the months following the October OPEC+ decision to cut oil production. The resulting market downturn briefly tested the critical $80/barrel mark before it made its partial recovery.

Should fears of a global recession materialize, the potential impact on Saudi foreign and domestic policies and programs could be significant. With nearly half of its GDP dependent on the oil sector, a sustained global downturn will likely push the Saudi budget into the red and force the first belt-tightening exercise in recent years. The kingdom’s powerful crown prince and de facto ruler, Mohammed bin Salman, will be faced with the need to prioritize among Saudi Arabia’s competing outlays on defense and security, economic development, and such high-profile vanity projects as NEOM and the Saudi-sponsored LIV professional golf tour.

Equally, a significant downturn can affect Saudi foreign policy priorities. A tightening export market could bring Saudi and Russian economic interests into conflict and renew the price war last witnessed in the spring of 2020. At that time, the Saudis initiated a massive expansion of production, triggered by Russia’s resistance to proposed production cuts in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in a 65% quarterly fall in the price of oil. Although the Saudi initiative (reinforced by demands for production cuts by the Trump administration) eventually forced the Russians to agree to the cuts, the conflict imposed costs on the Saudi government, which cut its planned capital expenditures by one-third and increased its budget deficit from 6% to 9%. A recession-induced drop in global energy demand could once again bring Saudi Arabia and Russia into direct competition, especially if Russian oil exports, heavily discounted to sustain production in the face of Western sanctions, threatened to cut into Saudi market share. The Saudis would be particularly sensitive to the effects of Russian discounts on their critical Asian markets of China, India, Japan, and South Korea.

Closer to home, pressure on the Saudi budget could force a retreat on regional foreign policy initiatives heavily built around riyal-diplomacy. Saudi Finance Minister Mohammed al-Jadaan signaled the change in Riyadh’s approach in his remarks at the World Economic Forum in Davos, on Jan. 18. Al-Jadaan told the audience that Saudi Arabia “used to give direct grants and deposits without strings attached and we are changing that.” Henceforth, the Saudis would expect recipient governments to undertake economic reforms, commenting that the Saudis “want to help but we want you also to do your part.”

The immediate target of the Saudi policy revamp could well be Egypt, which has thus far resisted accommodating demands by the international community to undertake broad reforms, including accepting conditions imposed by the IMF in exchange for a $3 billion loan approved in December. According to Maged Mandour, writing in the Arab Digest, “the time of lavish [Gulf] support has now passed; Sisi’s allies are finding themselves locked into an awkward and costly embrace with a regime that is increasingly becoming a liability.” Another potential target of changing Saudi policies is Pakistan. Although the Saudis recently participated in an international effort to help Pakistan stabilize its beleaguered economy, like Egypt, the Pakistanis are locked into a difficult negotiation with the IMF, which is demanding sweeping economic reforms in exchange for continued budgetary support. A harder line stance by the Saudis might well force the Government of Pakistan to accept measures it has resisted until now.

Thus, while changing Saudi foreign assistance policies might be painful for traditional recipients of its largesse, the overall regional impact of its budgetary constraint might be positive as it impels the Saudis to coordinate more closely with other international donors and demand that donees make the hard decisions to help themselves.

Image: Photo by Bandar Algaloud / Saudi Kingdom Council / Handout/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Acute economic pressures and geopolitical posturing in North Africa

Intissar Fakir

Senior Fellow and Director of Program on North Africa and the Sahel

Jonathan Winer

Non-Resident Scholar, North Africa and the Sahel Program

Across North Africa, the economic pressures that have accumulated in the aftermath of a shaky pandemic recovery and commodity inflation arising from the grinding Russo-Ukrainian war are likely to drive social unrest this year as regional governments seek to bolster their resilience.

Tunisia is experiencing an economic crisis that is even more acute than the one that contributed to the 2011 revolution. Under President Kais Saied, who has made himself a virtual dictator, youth unemployment has already climbed to 38% with no sign of abating, inflation is over 10% per annum, and both the government and major state-owned companies face bankruptcies. A highly anticipated deal with the IMF is now at a standstill, and confidence in Tunisia’s ability to find a way out of this economic abyss is low. Saied’s authoritarian overreach and conspiracy theory-prone approach is likely to galvanize an economically distressed population against his rule. This makes Tunisia the most susceptible North African state to social unrest and potential political instability.

Economic conditions in neighboring countries of the region also point to possible turmoil over the coming months: Libya’s youth unemployment is estimated at 50%, Algeria’s at 32%, and Egypt’s at 24%. The Libyan and Algerian governments have been able to use income from oil and natural gas exports to mitigate domestic inflation, which has stayed at 4.5% and 8.5%, respectively — compared to Egypt, where it has now reached 21%. But in Libya, senior government officials are reportedly discussing integrating the country’s armed groups into a single national security force, while declaring their own “state of emergency” that would replace the two existing competing Libyan governments for six months to a year in yet another transition pending elections. That kind of move could set off renewed conflict on the ground. A more probable risk is continued control of Libya’s west by the Dbeibah “Government of National Unity,” with de facto control in the east and the south remaining with forces led by warlord Khalifa Hifter and his sons, amounting to an informal partition of the country. The Algerian government’s social programs will provide some buffering against popular anger — putting off, yet again, the kind of economic overhaul measures the country needs. Meanwhile, in Morocco, the impact of rising inflation on a population with low purchasing power has worn out most citizens; however, years of thoughtful monetary policies and sound use of the fiscal space bolster the country’s overall political resiliency.

In terms of geopolitics, 2023 is likely to see North African governments continuing and potentially increasing their regional engagement despite, and in certain cases because of, their domestic vulnerabilities as they seek to showcase their relevance. For instance, Libya, which imports essentially all of its own food, has sent nearly a hundred truckloads of donations of staples like sugar, oil, flour, and rice to Tunisia, with further promises to fill empty Tunisian grocery shelves, as part of Libyan President Abdul Hamid Dbeibah’s food diplomacy. Similarly, Algeria is likely to bolster its regional diplomatic outreach as it enjoys the added geopolitical leverage that comes from its gas exports. Last year, Algeria emerged as Tunisia’s key regional supporter, drawing its smaller neighbor into Algiers’ foreign policy orbit. President Saied has few friends at the moment, so he will probably continue to rely on Algeria’s financial and ideological support. Finally, tensions between Morocco and Algeria are likely to fester — though remain constrained to the diplomatic realm — further polarizing the region and compounding other drivers of regional instability.

Follow on Twitter: @IntissarFakir

Image: Photo by Hasan Mrad/DeFodi Images via Getty Images

Syria faces new instability amid economic collapse and the rise of a narco-state

Charles Lister

Senior Fellow, Director of Syria and Countering Terrorism & Extremism programs

As Syria enters 2023, the multiple conflicts ongoing throughout the country show no signs of abating, while sources of continued instability persist. By most accounts, almost all aspects of the Syrian crisis are in a state of stagnation, with no light at the end of any tunnel. However, there is one dynamic that is markedly deteriorating and looks set to have a consequential impact on developments in Syria in 2023: the economy.

While Lebanon’s liquidity crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have all had deleterious effects on Syria’s already disintegrating economy in recent years, conditions have dramatically worsened since late 2022. The catalyst for this collapse was Iran’s decision to double the price of fuel offered to Syria’s regime and the requirement for prior payment in cash, rather than credit after the fact. Coming during the onset of winter, the resulting steep decline in fuel supplies had disastrous effects: spiraling inflation saw food and fuel prices surge by 30% and 44% respectively; transport became all but unaffordable; and electricity supplies in the capital Damascus declined to an average of one or two hours per day.

With 90% of Syrians under the poverty line, subsidies cut by 40%, and the average cost of living now 30-40 times the average salary, conditions in regime-held Syria have never been worse. Yet amid this economic collapse, the Assad regime has emerged as a narco-state of global significance, managing an industrial-scale drug production and smuggling effort focused on an illegal amphetamine known as Captagon. In 2021, at least $5.7 billion of Syrian-made Captagon was seized abroad, which regional intelligence officials believe accounted for only 5-10% of the total trade. That would suggest the value of the regime’s 2021 Captagon production was at least $57 billion — more than 20 times the national budget. Data for 2022 suggests even higher numbers.

While ordinary Syrians plunge into the economic unknown, the regime’s elite have more money than ever before — none of which is trickling down to the people. While Syria’s intractable crisis was already consolidating warlordism and a war economy driven by corruption and organized crime, the combined effects of the Captagon trade and economic collapse have exacerbated that considerably. As the central actor in the Captagon trade, Syria’s Fourth Division — commanded by Bashar al-Assad’s brother Maher — has become a security behemoth with unrivalled power and reach. Empowered by drug revenues, it has launched a recruitment drive to fill dozens of checkpoints recently acquired from other security bodies along Syria’s main roads linking Lebanon to Damascus and the south, as well as the coast to Homs and south toward Jordan and east toward Iraq.

The ever-widening chasm between the Assad regime and the people it claims to represent, and the Syrian economy’s guaranteed continued decline look set to be the cause of considerable instability in 2023. Neither Syria, nor Iran, nor Russia has the capacity to rebuild the economy and in the resulting vacuum comes only regime-facilitated criminality. It is hard to envision this state of affairs continuing to deteriorate without something giving.

Follow on Twitter: @Charles_Lister

Image: Photo by Fayez Nureldine / AFP) (Photo by FAYEZ NURELDINE/AFP via Getty Images

Little prospect for change in fragile states Lebanon and Iraq

Randa Slim

Senior Fellow and Director of Conflict Resolution and Track II Dialogues Program

If one were to go down the list of the 12 CAST indicators on which the Fragile States Index is based, Lebanon and Iraq check each and every one: no monopoly on use of force by the state security apparatus with private militias working inside and outside state structures; factionalized elites; inter- and intra-group political and socio-economic grievances; lack of confidence by citizens in state institutions and processes; failure to provide basic public services like water, electricity, health, and education; widespread abuse of citizens’ legal, political, and social rights; progressive economic decline; uneven economic development with wealth concentrated in the hands of a small group of political and business elites; flight of youth and technical expertise seeking job opportunities and hopeful futures elsewhere; proneness to shocks due to climate change; threats to food supply and health epidemics; high numbers of refugees and internally displaced persons; and external political and military intervention.

Should we expect change on any of these indictors in 2023? That seems highly unlikely. To start with, countries that fall into the fragility trap find it difficult to escape. As Tim Besley and Paul Collier argued in their April 2018 report Escaping the fragility trap, “Fragile societies are typically trapped in a syndrome of interlocking characteristics which makes it hard to make sustained progress. Usually, they are fractured into groups with opposing identities who see their struggle as a zero-sum game.” In a 2019 Brookings report A new approach to state fragility, Paul Collier makes the case that escaping the fragility trap requires working with state institutions that are willing and capable of implementing change and “pivotal moments of opportunity” to bring it about.

Neither of these two conditions is likely to materialize in Iraq and Lebanon anytime soon, let alone in 2023. Time and again, political elites in both countries have proven to be unwilling to implement policies that address drivers of state fragility. In Lebanon, state institutions have been hollowed out to the point that even if a political will to change the status quo were to materialize, it is questionable if it could be acted upon. When political elites and state institutions have no intention to enact and implement policies that could change the status quo in a transformative way, there is little that the international community can do to change their incentive structures. Lebanon is a case in point. Since the onset of the economic crisis in October 2019, neither sticks (sanctions) nor carrots (financial aid) have produced any discernible change in the political elites’ behavior.

When faced with “pivotal moments of opportunity” in the past, such as the 2019 protests, the elite pact underpinning the political system proved to be resilient. In both Lebanon and Iraq, political elites brought the protests down using the coercive power of state institutions and militias that are affiliated with them.

Regional dynamics compound the domestic political and structural impediments to change, thus helping perpetuate the state of fragility in Iraq and Lebanon. The failure of efforts to restore the Iran nuclear deal and increasing Arab-Israeli military ties, which Iran perceive to be directed against it, have escalated tensions in the region. This will make local stakeholders in both Iraq and Lebanon, especially those that are partners and proxies of Iran, even more resistant to change.

Fragile states are prone to conflict, especially countries like Iraq and Lebanon that have already experienced years of internal strife. In Iraq, the political stalemate that currently exists between cleric Muqtada al-Sadr and the Coordination Framework will not last. Iraqis are already protesting the economic conditions, which have worsened despite the surge in oil prices. The Iraqi dinar has lost 7% of its value since last November. The prime minister’s anti-corruption campaign has not made much progress. Relations between Baghdad and Erbil are likely to get worse in light of the Iraqi Federal Supreme Court ruling that monthly remittances to the Kurdistan Regional Government are “illegal and unconstitutional.” Political tensions between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) could potentially turn violent. In Lebanon, a lethal mix of an out-of-control economic crisis and political paralysis could plunge the country into a new cycle of violence.

Follow on Twitter: @rmslim

Image: Photo by AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP via Getty Images

Pakistan is headed for a politically tumultuous year

Marvin G. Weinbaum

Director, Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies

Pakistan has troubles galore. Together with soaring inflation, food shortages, a threatened sovereign debt default, and rising violence, its political system entered 2023 embroiled in a high-stakes showdown between political elites, leading to government paralysis and a sharp erosion of faith in democratic institutions. Rough and tumble politics is hardly new to a polarized Pakistan, but its concurrence with economic, humanitarian, and security crises seems to have made the country’s present difficulties more existential than ever before. The challenges facing this populous, strategically located, and nuclear-armed Islamic country are also spilling over into Pakistan’s relations with regional neighbors and countries further afield.

The latest period of political upheaval began in April 2022 with the ousting of the government of Imran Khan in a parliamentary vote of no-confidence that exposed the breakup of a military-civilian ruling condominium and the skillful deal-making maneuvering of a diverse 12-party opposition. But rather than Khan being put out to pasture, he rallied with an energic populist campaign that now looks likely to propel him back into office in the next national elections. The present political deadlock is specifically over the setting of a date for those elections — constitutionally mandated to occur by Oct. 12.

Capitalizing on his movement’s momentum, Khan and his Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) loyalists are seeking to force an early election, while an alliance led by the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) party is anxious to delay a vote as long as possible in the hope of building a record of policy accomplishments. To remain in power, the government has relied on its patronage networks and resorted to politicizing such pivotal state institutions as the country’s judiciary, Accountability Bureau, and Election Commission. In mobilizing his following, Khan has employed inflammatory rhetoric and maneuvered politically in ways that many believe overstep the limits of democratic contestation. Pakistan’s powerful military, for the time being on the sidelines but ever mindful of its own institutional interests, umpires the bitter rivalry.

A number of international actors are also keeping a close eye on political developments in Pakistan. Several countries are concerned over the ability of a distracted, politically paralyzed Pakistan to meet the heightened challenge of militant extremism. Although Khan has somewhat toned down his anti-American rhetoric, he continues to refer to the current government as “imported,” and his often-sympathetic views of the Pakistani and Afghan Taliban worry the United States and European powers. Several Gulf states that have for years turned to Pakistan’s military to provide regime security and value Islamabad’s regional diplomatic role need assurance of a politically predictable, stable Pakistan. So too does the international financial community, which, along with the Saudis, Chinese, and others, have invested so heavily in Pakistan.

The year 2023 likely holds the answer to many open questions. Among them, can Pakistan’s overheated political system succeed in containing electoral violence? Will the military keep its promise to refrain from interfering in the election process? Could a sweeping victory by Khan’s conspiratorial-laced populism reset politics in a way that sets Pakistan on a more autocratic course? What influence might a collapsing economy have on the political process, possibly postponing elections? Less in question is that Pakistan has a long way to go to establish a stable, functional political system, even more so to create a democratic political culture.

Research assistant Naad-e-Ali Sulehria contributed to this piece.

Follow on Twitter: @mgweinbaum

Image: Photo by RIZWAN TABASSUM/AFP via Getty Images

A consequential year for climate obligations

Mohammed Mahmoud

Senior Fellow and Director of the Climate and Water Program

All climate policy roads in 2023 lead to the upcoming U.N. Climate Change Conference, COP28, which the United Arab Emirates will host at the end of the year. The status of several climate obligations will have considerable influence on the proceedings.

First of all, COP28 will see the conclusion of the first global stocktake, a two-year process that started at COP26 in Glasgow. The purpose of this exercise is to assess the progress that participating countries have made toward achieving the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement. Specifically, it is meant to elucidate the current status of mitigation efforts intended to limit long-term average global warming to less than 2°C. Beyond mitigation, the stocktake will also assess the collective capacity of nations to be climate resilient through the implementation of initiatives that demonstrate a reduction in climate vulnerability — such as adaptation, financing, and green technology. More importantly, based on these assessments, the stocktake will provide direction on how parties should move forward, with the most direct implication being the countries’ respective Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

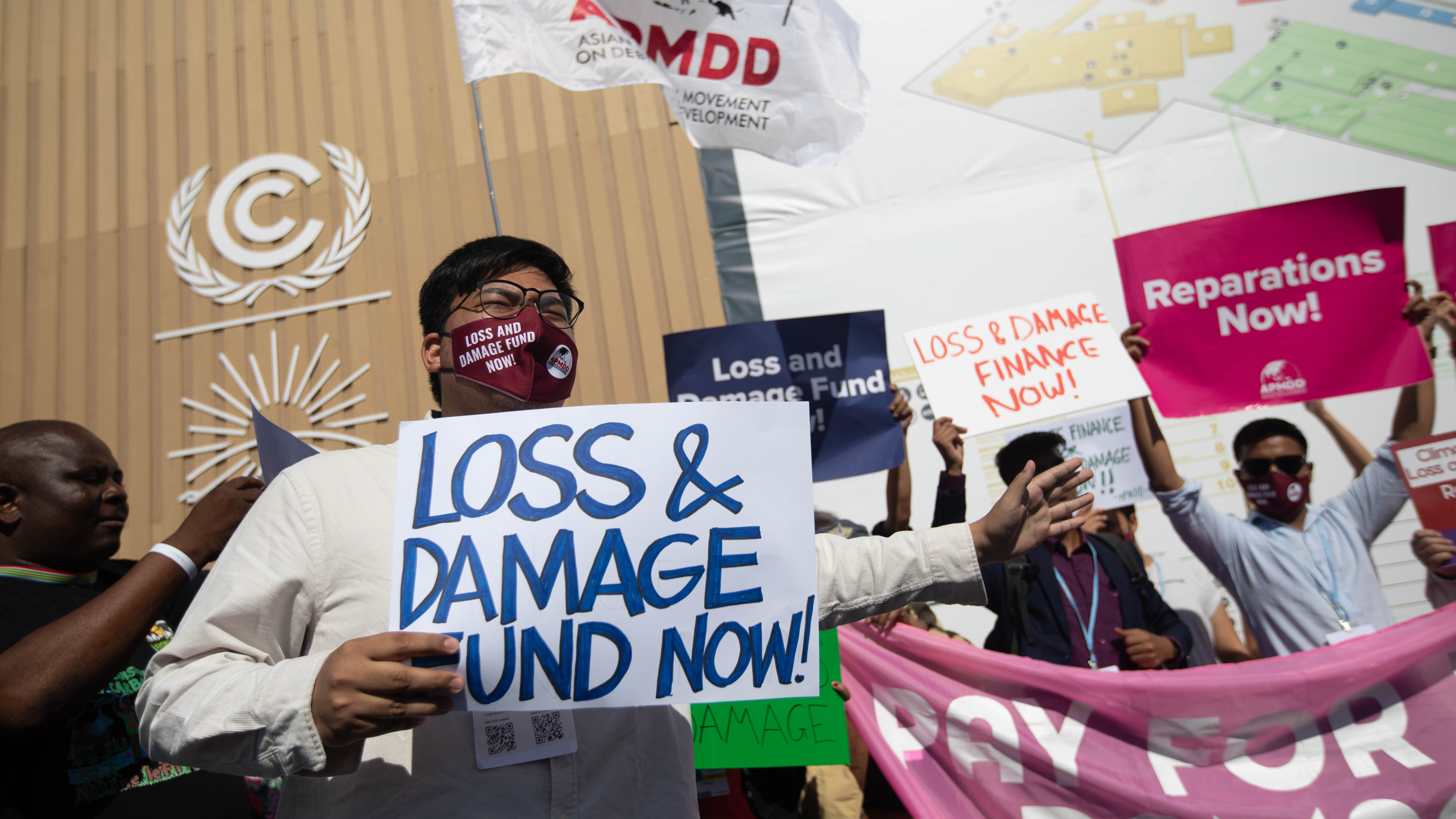

Just as the parties evaluate their climate mitigation efforts in this final year of the current global stocktake, they will also look to take actionable steps to close the gap on climate financing — both in terms of pledges and fulfillment. COP27 in Egypt concluded with an agreement on a loss and damage fund for climate-vulnerable and developing nations. Similarly, the U.N. Biodiversity Conference that took place late last year in Montreal, Canada, produced a “30 by 30” agreement committing to put a stop to biodiversity loss by protecting 30% of the Earth by 2030.

Both of these agreements were rightfully lauded as breakthrough deals that markedly moved the needle with respect to climate resilience in much-needed and neglected areas. But the deals themselves will mean little if they are not realized to their full and intended potential, with the financing required to do so. And while it is premature to assess the funding gap of these two most recent agreements, this issue of incomplete financing based on pledged commitments has plagued the Adaptation Fund, where only $230 million of new pledges were received at COP27. This is quite the financing shortfall when considering the U.N. Environment Program’s 2022 Adaptation Gap report estimated that the annual financing needs of developing countries through 2030 is $71 billion.

With these unresolved climate financing issues, we are now at a point where commitments are coming due. Making financing deals and securing pledges can no longer be considered adequate achievements when there is still insufficient implementation of funds to administer and execute initiatives that show tangible results on climate adaptation or mitigation. With the COP28 meeting serving as a global “heat check” on parties’ efforts on both fronts, 2023 will provide one last opportunity to make real progress on these outstanding climate obligations for both carbon-emitting and adaptation-implementing countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

Image: Photo by Gehad Hamdy/picture alliance via Getty Images

America’s ongoing crises of purpose and focus in the Middle East

Brian Katulis

Vice President of Policy

In 2022, the United States initiated a limited re-engagement of the Middle East, with President Joe Biden’s visit to Israel and Saudi Arabia in July highlighting the region’s importance as an arena for broader geopolitical competition with China and Russia.

But 2023 opens with many questions looming large about America’s priorities in the region. The most important question is how much the Middle East matters relative to the ongoing Ukraine war, dealing with China’s role on the world’s stage, and global security issues such as climate change.

As this set of essays highlights, the broader Middle East and North Africa faces no shortage of strains and threats: a fragile state system; pressing human security challenges, such as energy and food security; deep uncertainties in the internal politics of many leading countries of the region, including Turkey and Israel; and looming pressures from a possible global recession in the coming year.

In addition to these challenges, the early weeks of 2023 have already demonstrated how short-term crises and tensions can easily overtake any proactive agenda Washington might seek to set in its foreign policy and push it toward a reactive, crisis management mode. The quick visits of U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, CIA Director William Burns, and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken to the region in the opening weeks of 2023, with a focus on tensions on the Iran and Israeli-Palestinian fronts, highlight a desire to stay engaged in the region. But they also spotlight persistent uncertainties about whether the United States is operating with a cohesive plan to work with partners in the region who share the same set of priorities.

A central question American policymakers should ask at this midpoint in the Biden administration: is the U.S. driving an agenda that advances its interests and values, or is it merely reacting to the agendas of different actors from within the region and around the world?

Presently, the U.S. stance looks largely reactive, and the different elements of a proactive agenda do not seem to be synchronized with each other or with the efforts to respond to the daily crises that emerge. For example, the Negev Forum working group meeting organized in the United Arab Emirates, touted by a senior Biden official as “the largest gathering of Arab and Israeli officials since the Madrid process” in the 1990s, does not appear to be closely coordinated and integrated with other strategic elements of U.S. engagement in the Middle East these days, including the January visits of senior U.S. officials, the biggest-ever U.S.-Israel military exercise, and the efforts to re-think America’s overall policy approach on Iran.

Bigger strategic questions, including Iran’s growing and deepening involvement with Russia in the war against Ukraine, do not appear to have been balanced and mediated within a broader rubric for U.S. foreign policy. Nor do the modest U.S. policy measures in response to Iran’s ongoing street protests for freedom seem to have been coordinated with the administration effort to organize a follow-up to the 2022 Summit for Democracy later this spring.

Many questions loom about the individual elements of U.S. policy in the Middle East, but the most important question that remains unanswered is this: What’s the big idea?

Follow on Twitter: @Katulis

Image: Photo by RONALDO SCHEMIDT/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Main Image: Photo by Murtadha Al-Sudani/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.