Sudan has a longstanding strategic partnership with Turkey, forged on the basis of shared ideology and fostered by growing economic and political ties, that has proven resilient to regime change. Khartoum has not abandoned its relationship with Ankara despite the ouster of former President Omar al-Bashir in 2019 or the opposition of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Egypt, Turkey’s former regional rivals and more recent cautious partners. For now, Sudan is using the regional realignment between Turkey and the Gulf to maintain Khartoum’s relationship with Ankara, although this careful diplomatic balancing act could change because of the persistent protests by Sudanese calling for full civilian rule, a transition that would take Sudan’s strategic partnership with Turkey into unchartered waters.

Background

After the Arab Spring uprisings began in late 2010, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE became deeply concerned about the spread of political Islam in the Middle East. They believed it had the potential to undermine the security of their regimes, and they viewed Qatar and Turkey under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as responsible for spearheading its expansion. After the Egyptian military ousted then-President Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood in 2013, Turkey harbored members of the group’s Egyptian branch. The three countries also feared the support provided by the Sudanese regime under former President Bashir to Islamists in Libya, who later formed the U.N.-recognized Libyan government. The UAE in particular focused on providing military support for its ally, the Libyan warlord Khalifa Hifter, and his efforts to wrest control of the capital, Tripoli, home to the U.N.-recognized government. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE also had growing security concerns over Turkey’s presence in the Red Sea, as Sudan’s leasing of Suakin Island to Turkey in 2017 underscored the close economic and political relations between the two nations.

Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE had hoped that their support for Lt.-Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and his deputy Lt.-Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as “Hemedti,” in ousting former leader Bashir and his National Congress Party from power in 2019 would have driven a wedge between Sudan and Turkey. The three allies had sought to shape Sudan’s foreign policy in the Red Sea and Africa and prevent the former Bashir regime, backed by Turkey and Qatar, from regaining power. They believed that the Sudanese military, particularly Hemedti and his paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, was not ideologically committed to the former regime. However, their focus on ensuring that the Bashir regime did not regain power and on preventing any other group in Sudan from posing a security threat left them blind to the deep and enduring strategic partnership between Sudan and Turkey.

A geopolitical advantage

Sudan’s geostrategic position makes it important for Turkey’s engagement with Africa, especially the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa, and this geographical reach is essential to Ankara’s neo-Ottoman policy. Turkey sees its interest as providing an alternative model of influence in the region, different from the U.S.’s security-driven model or the Chinese economic-interest-driven model. The Turkish model, by contrast, focuses on a combination of humanitarian and development projects, economic and business relations, and diplomatic and, later on, defense ties.

Sudan’s position as a gateway between the Middle East and Africa encouraged Turkey to deepen its formal relations with the country. Sudan hosted Turkey’s seventh Turkish-African Congress in Khartoum in 2012, where policymakers, researchers, and business leaders were present to help formulate Turkey’s foreign policy in the region. In 2014, then-Deputy Prime Minister Emrullah İşler announced that Turkey was working toward upgrading its relations with Sudan to a strategic partnership.

For Turkey, Sudan’s geopolitical importance also lies in its membership in several regional organizations, such as the African Union, Intergovernmental Authority on Development, Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, International Conference of the Great Lakes Region, and Community of Sahel-Saharan States, through which Turkey wishes to expand its influence in Africa. Importantly, Sudan itself has also proven able to shape policy in neighboring countries by making use of ethnic communities along its border regions or supporting other countries’ rebel groups. For example, in retaliation for Chad’s support for Darfurian rebels hailing from the Zaghawa — an African tribe that stretches from Chad into Darfur — the Bashir regime created and sponsored the Rally for Democracy and Liberty, which attacked Chad in 2006. Khartoum’s support for the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement in Opposition in the South Sudan civil war that broke out in 2013 followed a similar pattern as well.

Soft power influence

The ideological similarities between the Bashir administration and Erdoğan regime complement Turkey’s strategic interests in Africa. The Bashir regime emerged out of the Sudanese Islamist Movement (SIM), a political movement that took power through a military coup in 1989 and focused on imposing religious conservativism on a multi-ethnic and multireligious society. The SIM ideology is remarkably similar to that of Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), which came to power through democratic elections. The AKP emphasizes a desire for Turkey to be a model for the Muslim world and provide an alternative to a West that lacks moral authority. Shared ideology has thus allowed for the implementation of strategic relations between the two nations.

To deepen its strategic ties with Sudan, Turkey has focused on using soft power by developing infrastructure. The construction of the King Nimr and al-Halfaya bridges have been the most important of such projects. Turkey has also used its development agencies, including the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA) and the Turkish Red Crescent (Kızılay), to renovate a medical center catering to the education of children with Down syndrome and to construct the Nyala Hospital, seen as important contributions to a nation plagued by an endless cycle of internal conflict as a result of the Bashir regime’s aggravation of tensions between Arab and African tribes.

Turkey has been actively spreading its political ideology in Sudan to counter the Gulf states’ spread of Wahhabism, and this effort has had a significant impact in the country over time. Since 1992, Turkey has provided 700 scholarships to Sudanese students under the Türkiye Scholarships program. Erdoğan also looked favorably upon Sudan when the Bashir regime transferred schools linked to the Gülen movement to Turkey’s Maarif Foundation in 2016 following the Turkish government’s accusation of Gulenist infiltration of state institutions and responsibility for the failed coup attempt of 2016.

Economic and security ties

Over the past decade, Turkey has deepened its business and security relations with Sudan. In the business sector, Turkish companies spent $300 million on infrastructure projects in Sudan and bilateral trade reached $295 million in 2013. In 2017, on his visit to the country, Erdoğan was accompanied by a delegation of 200 businesses men and military officials; he signed 21 agreements, including a $650 million, 99-year lease of Suakin Island and a pledge to increase the volume of bilateral trade to $10 billion annually. Sudan proved a willing partner, as the Bashir regime was in need of financial support after two decades of U.S. sanctions and the loss of over 70% of the nation’s oil revenue when South Sudan declared independence in 2011. The volume of trade between both Sudan and Turkey reached $480 million in 2020, and Turkish investment in Sudan hit $600 million in the same year, according to the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This is line with the broader expansion of trade between Turkey and the continent of Africa, which has been steadily increasing in recent years, reaching $25.3 billion in 2020.

The Sudanese-Turkish relationship has also been driven by Turkey’s desire to include Sudan in its regional defense plans. Joint military drills occurred in 2014 and 2015, when Turkish warships docked in Port Sudan, highlighting Turkey’s growing interest in establishing a naval presence in the Red Sea. This regional effort extended beyond Sudan as Turkey built its largest overseas military base in Somalia in 2017, at a cost of around $50 million, with plans to train 10,000 Somali soldiers as well as Turkish personnel.

Ankara’s defense ties with Khartoum are part of Turkey’s broader push to tap into the lucrative arms market in Africa, currently dominated by Russia, which had a 49% market share from 2015-19, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Turkey’s defense business goals in Sudan are exemplified by the career of Oktay Ercan, the chair of Turkish firm Barer Holding. Ercan arrived in Sudan in 2002 and developed business relations with the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Ministry of Defense through Sur International Investment, a military textile mill of which he is the executive director and a shareholder, alongside the SAF and the Qatari Armed Forces. In essence, the relationship with the former regime and the SAF allowed him to create a business model — involving the establishment of joint ventures with parastatal companies in the military-industrial complex, typically focused on military textiles — that has since been replicated in Nigeria, Chad, and, as of March 2022, in the Ivory Coast.

A strain on relations, yet continuity persists

The strategic partnership between Sudan and Turkey was put to the test after the ousting of President Bashir by Burhan and Hemedti. There were signs that the Suakin agreement would be canceled in 2019, when Sudan’s military leaders snubbed Qatari envoys and ordered the Sudanese ambassador to Qatar to return home after the closure of the local Al-Jazeera bureau. Qatar is Turkey’s closest regional ally and became involved in Turkey’s Sudan policy through a $4 billion investment in the renovation of Suakin port. The downgrading of relations with Qatar seemed to suggest that Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE had succeeded in isolating Qatar from Sudan, and in turn Turkey from the Red Sea.

Another challenge to the strategic relationship was the civil-military partnership put in place in Sudan due to the transition agreement between the military and the civilian opposition Forces of Freedom and Change. This agreement gave the civilian wing of the government, fiercely opposed to the remnants of the Bashir regime, a certain amount of power to hunt down individuals they accused of having links to the regime. As a result of these arrests, multiple leaders and supporters of the former regime fled to Turkey to organize, regroup, and prepare their return to power in Sudan.

The civilian component of the Sudanese government has been using the country’s judicial system to arrest and prosecute associates of the former regime, such as Ercan. In December 2019, the prosecutor-general ordered Ercan to hand himself in for investigation, on the basis of financial irregularities stemming from his links with the former Bashir regime. However, his continuing ties with the Sudanese military, most likely through Sur International Investment, facilitated his release in 2020.

Ercan’s release from prison came against a backdrop of a fierce struggle between the military and civilian components of the Sudanese government regarding the country’s foreign policy direction. This struggle became evident when Burhan, the head of Sudan’s Sovereign Council, took the lead in establishing relations with Israel in February 2020, with the support of the UAE. Although Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE hoped Burhan would curtail Sudan’s friendly relations with Turkey, the strategic relationship between Ankara and Khartoum proved much deeper than the three countries had anticipated.

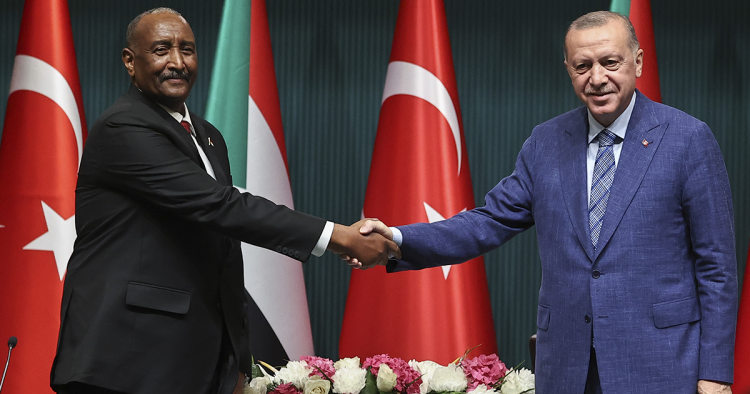

Perhaps Turkey’s rivals should not have been surprised; after all, Burhan and other generals in the SAF had been members of the SIM, with all its ideological, economic, and security ties to Erdoğan’s Turkey. For this reason, while Burhan wished to be assertive in the foreign policy domain, in practice he has adopted a largely similar foreign policy to that of Bashir. His official visit to Turkey in August 2021 emphasized Khartoum’s continuing strategic importance in Ankara’s Africa policy.

The deep strategic relationship between Sudan and Turkey has proven to be resilient over time, although the recent reconciliation between Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE will put this to the test. How Burhan balances Egypt’s lack of trust in Turkey will likely determine the future of the relationship between Sudan and Turkey. The close ties between the Egyptian Armed Forces and the SAF have encouraged Egypt to support Burhan, even though he is part of the SIM, which itself has links to members of the outlawed Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood who settled in Turkey. At the same time, Turkey also has close relations with Ethiopia, which has been building the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam that Egypt believes poses a threat to its water security. The recent regional realignment has not been tested in the Red Sea, and how it plays out there will help to determine just how sincere it really is, in turn affecting the foreign policy calculations of both Burhan and Hemedti. Moreover, were Sudan’s leadership to change again, as a result of the ongoing protests calling for full civilian rule, the impact on Turkey’s strategic interests in the region would be unclear and it could potentially spell the end for the shared ideology and thus the warm relations between Sudan and Turkey.

Jihad Mashamoun is a Sudanese researcher and a political analyst on Sudanese affairs. Holder of a doctoral degree in Middle East Politics from the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, University of Exeter, he has authored and co-authored numerous articles on the recent Sudanese uprisings and Sudanese affairs, and has provided interviews on Sudan for radio, print, and television news channels. Follow him on Twitter @ComradeJihad. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Emin Sansar/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.