This essay is part of the series “Turkey Faces Asia,” which explores the development of cultural, political, and economic links between Turkey and the Asia Pacific region. See more ...

Turkey’s foreign policy under the current Justice and Development Party (AKP) government continues to attract widespread attention by scholars and policy circles alike. Over the past decade, the way Turkey has formulated and implemented its policies toward the rest of the world has transformed from a traditionally status quo-ist and reactive stance that emphasizes maintaining close relations with the West to a more assertive, multidimensional, and proactive approach with a broader geographical scope. While the process of accession to the European Union (EU) remains the main axis of its foreign policy, Turkey is now showing greater interest in regions hitherto neglected, including Asia, and this interest is materializing in the form of greater dialogue between countries, expanding economic and commercial relations, and frequent exchanges between peoples.

Is it then possible for us to claim that Turkey, as a country bridging Europe and Asia, is turning its back on the West and heading toward Asia? It is critical to address the questions of how and to what extent Turkey’s relations with this region have been developing, and whether as an implication of the paradigm shift in its foreign policy Turkey envisages itself as a part of a wider Asian community.

Turkey’s Evolving Foreign Policy Paradigm

Turkey’s political scene dramatically changed following the general elections in 2002, which brought the AKP to power. With a single-party government with a parliamentary majority bringing about political stability after the turbulent 1990s and the economy returning to a growth trajectory after severe economic crises, policy making broke the deadlock of the previous coalition governments. Progress has been seen in every field of public policy, and foreign policy has been no exception.

Particularly after the AKP commenced its second term in 2007 and Ahmet Davutoğlu, a professor of international relations and chief foreign affairs advisor to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, was appointed foreign minister in 2009, Turkey has launched several foreign policy initiatives aimed at fostering ties with hitherto excluded or superficially handled nearby neighbors and regions. Such developments have marked the evolution of a new foreign policy paradigm based on what Bülent Aras calls a “novel geographic imagination.”[1] While Turkey’s new foreign policy cannot bring the desired results in every case, and while it frequently comes under criticism, particularly in the aftermath of the Arab uprisings, to which many deem Turkey to have failed to respond appropriately, it is an undisputed fact that Turkey is now more active and assertive in its foreign policy endeavors.

In regard to the factors influencing Turkish foreign policy and the dynamics behind the paradigm shift, at the international level structural changes in the global economic system are a determinant of how Turkey shapes its relations with the rest of the world. Turkey’s disappointment with the EU accession process and the transformation of the political scene in its neighborhood are factors shaping Turkey’s regional preferences. At the domestic level, while the strong support enjoyed by the AKP is commonly deemed the most important factor ensuring that the government can translate its foreign priorities into policies, scholars also point to the impact of changes in the domestic sphere, such as the rise of a conservative ideology based on an Islamic worldview, structural shifts in Turkey’s economy, and the personality of state leaders.

Turkey’s foreign policy activism under the AKP can be regarded as the product of both “push” and “pull” factors.[2] The new foreign policy stance has not only been a government initiative; it has also been a response to the structural developments at the global and regional level. In this respect, stalled negotiations in the EU accessions process and the growing disillusionment with the European project among both policy makers and the public, together with shifting balances in domestic politics and the emphasis on Turkey’s Muslim identity, can be thought of as “push” factors driving Turkey’s foreign policy attention away from Europe and toward the Middle East and North Africa. In the meantime, changes in the global system and the shift from polar structures and hegemonic stability to participatory global governance as the key to international political and economic well-being have been a “pull” factor drawing Turkey into multilateral coalitions and requiring it to act as a responsible global actor. These factors do not function in isolation; push and pull factors combine to determine Turkey’s foreign policy stance.

Economic considerations in the formulation of policy are a crucial defining aspect of Turkey’s evolving foreign policy. Stronger economic ties with the rest of the world constitute both an end and the means to an end for Turkish policy makers.[3] They are an end in itself in that improving economic and commercial relations with a diverse range of regions gains access to new markets for Turkish export products and attracts foreign capital for investment projects. Economics is also the means to an end with respect to foreign policy, as Turkey’s ambitions to increase its global and regional influence relies on its ability to project power abroad, which can only be accomplished through a growing economic presence in the neighborhood and beyond. At the end of the day, economic factors are shaping Turkey’s foreign policy as never before; we are witnessing, in the words of professor Kemal Kirişci, the “rise of the trading state.”[4] Under conditions in which economics play a crucial role in foreign policy, the state engages with non-state actors, particularly those with economic leverage such as large corporations and business associations, in its formulation and implementation of policy. Public-private partnerships then become a vital component of foreign policy making.

Rapidly rising figures of trade, investment, and capital flows is thus one way to move toward the objective of increasing a country’s regional and global influence. In this respect, the share of Asia in Turkey’s foreign economic relations is rapidly increasing.

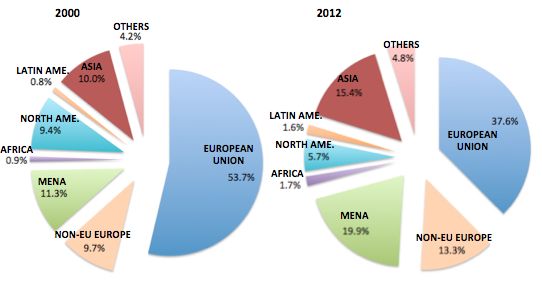

Figure 1. Turkey’s Trade Partners

Source: Prepared using data released by the Turkish Institute of Statistics (TÜİK).

As can be seen in Figure 1, changing patterns of Turkey’s foreign trade between 2000 and 2012 represent a shift away from developed economies toward developing ones. The share of Asia[5] in Turkey’s foreign trade has moved up from 10.0 percent to 15.4 percent.[6] In 2000, Turkey’s trade volume was $82.3 billion, of which $27.8 billion was exports and $54.5 billion imports. In this year, Turkey’s trade with Asia totaled $8.2 billion, of which $6.9 billion was Turkey’s imports, thus pointing to a serious deficit. In 2012, Turkey’s foreign trade amounted to $389.1 billion, with exports totaling $152.5 billion and imports $236.6 billion. In this period, trade with Asia was $60.2 billion, composed of $10.6 billion of exports and $49.6 billion of imports. In short, Asia’s share in Turkey’s trade is increasing, and so is Turkey’s deficit with Asia. In the meantime, Asia is also increasingly attracting Turkey’s outward investment and capital flows, although in nominal terms the continent is still far behind Europe, the United States, the former Soviet Union, and the MENA region. In 2000, Turkey’s official investment stock overseas was $3.8 billion, of which only $4.7 million was invested in Asia, a share of 1.2 percent.[7] In 2012, Turkey’s investment stock overseas was $29.7 billion, and by then $776.3 million was invested in Asia, meaning that Asia’s share had gone up to 2.6 percent.

While increasing economic ties with various parts of the world significantly contributes to Turkey’s goal of expanding its regional and global influence, Turkish policy makers are also engaging in more personal efforts to expand the country’s global outreach, with senior statesmen such as President Abdullah Gül, Prime Minister Erdoğan, and Foreign Minister Davutoğlu making frequent visits abroad in the company of not only politicians and bureaucrats but also business executives and academics. Other initiatives include the opening of new diplomatic missions across the globe; Turkish Airlines launching flights to new destinations; visa requirements being mutually lifted with different countries; and establishing Turkish schools and cultural centers promoting Turkish language and culture in different geographies. Significant efforts are hence being made to increase dialogue and understanding between Turkey and Asian countries.

A good indicator of how Turkey is expanding its global outreach is official state visits. A comparison between Prime Minister Erdoğan’s visits and those by his predecessor Bülent Ecevit, who was prime minister between 1999 and 2002, clearly illustrates the change. During his three years in office Ecevit made 18 visits to 17 countries, with an average of 6.0 visits per year. Erdoğan, during his nine years in office since 2003, has made 267 visits to 88 countries, with an average of 29.7 per year. While Ecevit visited only one Asian country, Erdoğan has visited 14 of them.[8] And it is not only the prime minister who is frequently traveling; ordinary Turkish citizens are doing so too, helped by a series of agreements over the past few years that lift visa requirements with certain countries. As of August 2013, Turkish (ordinary) passport holders can travel to 69 countries without having to obtain a visa prior to their visit, including 15 Asian countries.[9]

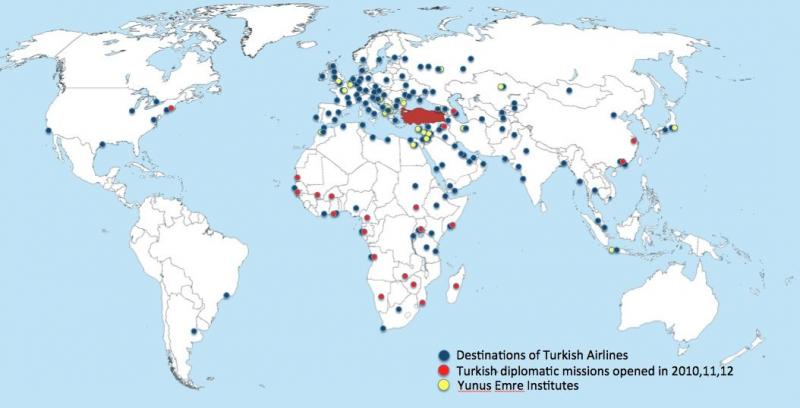

Figure 2. Turkey’s Global Outreach

Source: Prepared using data from Analist, January 2013, 28-29; Yunus Emre Foundation web site.

Figure 2 shows that while Europe and the MENA region remain the focal points of Turkey’s global outreach, there is also a rapidly growing interest in Africa and Asia. As of the end of 2012, Turkey had 204 diplomatic missions in 122 countries, 91 of which were in Europe and 53 in Asia.[10] The map shows that over the past three years most of the missions opened abroad were in Africa, totaling 29 as of this writing. In the meantime, Turkish Airlines is flying to 167 destinations in 90 countries, including 14 countries in Asia, and together with Africa, Asia is home to new destinations for the carrier. On the cultural side, Yunus Emre Cultural Institutes, which aim at “improved promotion and teaching of Turkish culture, history, language, and literature,”[11] have opened 36 branches since the organization’s establishment in 2007, and while the majority of them are in Turkey’s neighborhood, there are plans to open more institutes in Asia in addition to the two already in operation in Tokyo and Jakarta.

In sum, Turkey’s new foreign policy paradigm aims to actively engage various parts of the world to increase Turkey’s influence at both regional and global levels, and this approach is materialized through concrete efforts by the Turkish state as well as civil society. In order to better understand Asia’s place in Turkey’s foreign policy, however, we need to examine Turkey’s relations with Asia at the bilateral level.

Turkey’s Bilateral Relations with Asian Countries

During the 1980s and the 1990s, Turkey had its soundest relations in Asia with Japan, followed by Korea. During the 2000s, however, Turkey’s interaction with China came to overtake those with Japan and Korea. The most important reason for this tendency is the rise of China as a global power and Turkey’s desire to engage the new global giant on mutually beneficial terms. This change of roles can be clearly seen in trade relations.

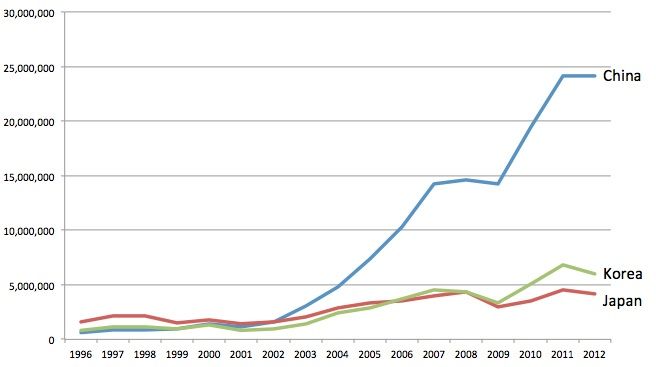

Figure 3. Turkey’s Trade with Japan, China, and Korea

Source: Prepared using data from the Turkish Institute of Statistics (TÜİK).

As shown in Figure 3, until the year 2000 Japan was the main Asian trade partner of Turkey, followed by Korea and China. After 2002, Turkey’s trade with China skyrocketed, while trade with Korea and Japan recorded only modest increases. As of 2012, for each $1 of goods Turkey has traded with China, its trade with Korea and Japan is 25 cents and 17 cents, respectively. This, however, does not necessarily mean that Turkey is turning toward China at the expense of its relations with Korea and Japan, or that that there is an overall deterioration in Turkey’s relations with these two countries. In contrast, while China has become a major economic partner for Turkey, political problems persist between the two countries, while Turkey’s relations with Japan and Korea are to a great extent politically problem-free.

Turkey’s relations with Japan, China, and Korea provide strong examples of how economic and political aspects of a bilateral relationship can reinforce each other in order to produce mutually beneficial outcomes. Turkey’s relationship with Japan dates to the late nineteenth century, and its relationship with Korea dates to the Korean War of 1950-53. In both cases favorable political relations and strong mutual understanding have always been evident, which has provided a fertile ground for improved economic relations. Turkey’s relationship with China, in contrast, has been marked by turbulent relations in the political realm since 1971, when diplomatic relations were established. However, the growth of economic relations after the early 2000s has had a positive spillover effect on these political issues.

The most striking aspect of Turkey’s relationship with China is the rapid growth of trade volume between the two countries and a similarly rapid increase in Turkey’s deficit against China. In 2012, Turkish-Chinese two-way trade totaled $24.1 billion, compared with a mere $1.1 billion dollars 12 years earlier. China’s share in Turkey’s total trade is currently 6.2 percent, up from 1.5 percent a decade earlier, and the change appears even more significant considering that the 24-fold increase in the volume of Turkish-Chinese trade between 2000 and 2012 occurred over a period when Turkey’s total trade volume increased less than five-fold, from $82 billion to $389 billion. Turkey’s imports from China are much higher than its exports to this country; this is a serious problem, particularly given Turkey’s chronic current account deficit. In 2012, Turkey exported $2.8 billion of products to China, while its imports amounted to a massive $21.3 billion, meaning that for every $1 of products Turkey buys from China, it sells only 13 cents. A reversal of this situation, or at least a gradual narrowing of the gap, seems unlikely to occur anytime soon, not only because low-cost Chinese products offer a handsome premium for Turkish importers and have a positive effect on the purchasing power of Turkish consumers, but also because a significant portion of imports from China are intermediary and investment goods that are used as inputs for final products assembled in Turkey and exported to third markets. In brief, imports from China offer certain advantages for Turkey’s economy, and they are a key variable determining the cost structure of Turkey’s exports. Nonetheless, the widening gap in bilateral trade with China also contributes to Turkey’s current account deficit, and the task faced by Turkey is to compensate for the effects of its imports from China.

While trade figures may not paint a rosy picture for Turkey, the other part of the story is that Turkey is experiencing a paradigm shift with regard to how best to approach and engage with China—a shift that is gradually taking its focus from short-sighted calculations to the establishment of a longer-term, sustainable, and mutually beneficial economic relationship.[12] During the 1980s, when both countries had begun to integrate with world markets, Turkey saw China as a single huge market with enormous untapped opportunities. The idea then was “sell a single orange to every Chinese person and become rich;” however, both bureaucrats and businessmen found out very soon that penetration of the Chinese market was not that easy. Businessmen going to China to export their products mostly failed to do so, not only because of the complexities of developing business deals in an unknown environment, but also because their products did not adequately match Chinese demand and preferences. Instead, they saw opportunity in low-cost Chinese products and thus returned home as importers. As a result, from the mid-1990s, Turkey’s economic approach to China has been marked by short-term, individual profits. Though some Turkish companies invested in China and commenced production there during this period, they numbered no more than a handful.

The paradigm shift began around the mid-2000s, when Turkey’s foreign economic policy makers adopted a two-sided approach to economic relations with China—an approach that resonated with the business community. Efforts were made to diversify export products and increase market penetration in order to find larger shares for Turkish products and, more importantly, to minimize the negative impact of Chinese trade on Turkey’s current account deficit. The emphasis also shifted to establishing longer-term investment relations, with the aim of attracting more Chinese capital and investment to Turkey—a wise aim, given that China’s capital accumulation and investment potential, rather than cheap imports, promise greater, more effective, and sustainable benefits for the Turkish economy. There is reason to believe that the paradigm shift from short-term trade calculations to long-term investment relations will produce concrete results in the near future, because Chinese companies, primarily the state-owned enterprises, have already become involved or at least registered their interest in large-scale industrial and infrastructure projects in Turkey. These projects include hydropower and mining projects, telecommunications, railroads, contracting projects, and nuclear energy.

Turkey is also increasingly interested in the technology component of investment from China, with communication software standing out as particularly significant. The Chinese firm Huawei has been a main source of research and development in this field. Active in the Turkish market since 2002, Huawei equips Turkey with 3G technology that is in step with the fast growth in the telecom market, and through its R&D center in Istanbul it operates a technology center serving Turkey and its regional neighbors. Another strategically important technological cooperation concerns Turkey’s space satellites. The first satellite (of three) that will soon be completed and launched was manufactured in Turkey with indigenous software programming and hardware but launched from the Gobi desert in China. The satellites are significant in that they will aid the Turkish government in obtaining intelligence and enhance its capacity to monitor and observe. Finally, a decision made by the Turkish government in September 2013 to co-produce a long-range air and missile defense system with a Chinese firm is a clear indicator that the two countries intend to expand their technological cooperation in this particular field of industry as well.

Hence, as strategic partners, Turkey and China are focusing on developing their economic relations on a long-term, sustainable, value-added and mutually beneficial basis, a trend that has effects on the political realm. Such effects can be seen in the Uighur issue, that is, the Turkic-Muslim minority living in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Until the mid-1990s, Ankara gave an almost free hand to Uighur diaspora associations in Turkey demanding the liberation of Xinjiang from Chinese rule. However, the Turkish government eventually adopted a more balanced approach, permitting the associations to operate within the boundaries of Turkey but not allowing their activities to jeopardize relations with Beijing.[13] Thus, maintaining cooperation with the Chinese government while at the same time defending the economic and cultural rights of Uighurs as citizens of China appears to be Ankara’s preferred option. This stance enables Turkey to defend the rights of the ethnic Turks in the Xinjiang Region without confronting Beijing.

Further, recent events reveal the development of a mutual understanding between the two governments with respect to Xinjiang. In June 2009, President Abdullah Gül made an official visit to China accompanied by a delegation of businessmen with an itinerary including Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang. Only a few weeks after this visit, riots broke out in the region, and more than 200 individuals lost their lives. Turkey reacted strongly against the violence in Xinjiang, with Prime Minister Erdoğan explicitly stating that what happened was “almost genocide.”[14] Although these remarks briefly strained Turkish-Chinese relations, the two sides soon reached reconciliation, and within a few months new trade agreements were signed, paving the way to the announcement of a “strategic partnership” between Turkey and China in November 2010. In February 2012, the new leader of China (then in his capacity as the Vice President) Xi Jinping visited Turkey, followed by a visit by Erdoğan to China two months later.

While these developments point to progress in relations between the two countries, threats exist as well. The most significant of these threats arises from the shifting geopolitics and geoeconomics of the Middle East, which may bring about larger areas of conflicting interests between Turkey and China. In February 2012, when China vetoed a UN Security Council resolution that would have imposed sanctions on Syria’s leadership, Turkey’s reaction was a strong one. In a clear criticism of China, Erdoğan stated, “No matter what benefits they expect, it is unacceptable that countries are providing the tyrant with a license to kill.”[15] Though the Syrian veto did not snowball into a major controversy between the two countries, the increasingly complicated situation in the Middle East may make it more difficult for Turkey and China to resolve their differences. Undoubtedly, Turkey will not want to be sidelined and will demand to have its own position—one that does not necessarily accord with that of the Chinese.

It is important to note that China’s motivation for closer relations with Turkey is due to Beijing’s understanding that the connection aids its domestic problem of Uighur activism. Indeed, the Turkish government supports the territorial integrity of the People’s Republic and opposes separatist activity within its borders. However, the development of relations based on this issue is not necessarily attractive to Turkey in terms of business concerns. While Turkish companies are interested in Xinjiang, the ultimate goal is to be in the same market as European and U.S. firms. As such, even if China urges Turkey to invest in Xinjiang’s industrial zone, Turkey still desires access to the A grade industrial zones along China’s east coast.

Japan is Turkey’s oldest partner in Asia, and relations between the two countries have always been close. As Japan developed economically in the post-war period, and particularly after Turkey began to liberalize its economy in the 1980s, economic relations between the two flourished. There was not only trade between Turkey and Japan, but also several Japanese corporations invested in the Turkish market and established production facilities there. In brief, favorable political relations provided the background for growing economic relations.

These relations are currently stronger than ever, as evidenced in 2010, when Turkey celebrated the Year of Japan through a series of cultural activities. There has been, however, a significant slowing down in economic relations, which can be partly explained by the overall slowdown of the Japanese economy. In 2000, Turkey’s trade with Japan was greater than its trade with China. In that year, Turkey exported $149.5 million of products to Japan, importing $1.62 billion in return, which made for a total trade volume of $1.77 billion. In 2012, Turkey’s exports to and imports from Japan amounted to $528 million and $3.6 billion, respectively, with a total trade volume of $4.13 billion. Between 2000 and 2012, when Turkey increased its trade with China 24-fold as discussed above, its trade with Japan only increased 2.4 times.

However, in the field of investments, we find a different situation.[16] Japanese companies have entered the Turkish market through joint ventures with local partners, and according to data released by the Turkish Ministry of Economy, there are 166 companies with Japanese capital in Turkey as of June 2013.[17] These companies operate production facilities in Turkey, and they export a large portion of their output to third countries, particularly to the EU, with which Turkey has had a customs union since 1996. The union enables companies in Turkey to export to European markets, including those in Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, and Israel, without facing tariff barriers. Thus, while Turkey is running a widening deficit with Japan in terms of direct trade, Japanese investment contributes indirectly to Turkish exports through the foreign sales made by Turkish-Japanese joint ventures. It should also be noted that Turkey has a long-standing interest in acquiring technology from Japan, and while trade figures are important, Japanese technology and know-how matter more for Turkey in the long run.

Yet it must be noted that the slowdown in the economic exchange between the two countries has affected investments as well. Companies with Japanese capital have been operating in Turkey since 1987, and several Japanese household names, such as Toyota, Honda, Isuzu, Bridgestone, Mitsui, Sumimoto, and Marubeni, have established themselves in the Turkish market. Starting in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the flow of investment capital from Japan to Turkey lost its pace. While the adverse economic conditions Japan has been experiencing are one reason for this downturn, another is that the business environment in Turkey has, at least until recently, failed to offer Japanese decision makers favorable and attractive conditions. The Turkish-Japanese Business Council argues that Turkey’s failure to achieve a certain level of economic political stability, transparency, quality of product, and infrastructure, as well as the complexity of Turkish bureaucratic procedures, have been the major reasons that have discouraged Japanese companies from investing more in Turkey in recent years.[18]

The top priority of the Turkish government in its relations with Japan is to reverse this situation. In November 2008, when Gül visited Tokyo, his first remarks to the Japanese press were that he came “not for a leisure trip, but to ensure that Turkey’s relations with Japan, which are very good in friendship and politics, also reach the same level in economy-related matters.”[19] During this visit Gül met in person with the heads of Japanese corporations, particularly those from the automotive sector, and informed them about incentives the Turkish government would offer.

Depending on developments in the Japanese and Turkish economies, it is possible that Japanese investment in Turkey could return to a growth trajectory in the near future. For example, the Turkish government’s May 2013 decision to hire a Japanese-French consortium to build the second nuclear plant in Turkey (in Sinop) represents a new surge in relations. Despite controversy due to anti-nuclear groups in Turkey as well as strong anti-nuclear public opinion in Japan fueled by the Fukushima disaster, the Turkish government has pursued nuclear energy due to its plans for growth in the next decade that will necessitate high energy use. The establishment of a Turkish-Japanese Technology University that will include a nuclear physics program to train staff for the plant, as well as a Japanese bid to construct a bridge on the Dardanelles, are also on the agenda.

Japan’s place in the Turkish government’s long-term foreign policy vision is not limited to economics. Remarks by Davutoğlu in a meeting with his counterpart, Koichiro Gemba, in January 2012 show that Turkey is willing to translate its good relations with Japan into a strategic partnership. Davutoğlu said,

[Turkey] deems Japan as an important partner in all regional issues, as a strategic partner. It is especially important for us to develop a joint Asia strategy with Japan. Strategies to be developed by two countries at both ends of Asia who are also G-20 members and have dynamic economies will open up new horizons for the content. Furthermore we place a special emphasis on joint work to be undertaken in regions like the Middle East, Central Asia, and Africa. Finally, in the global arena we are the founders of a joint platform on nuclear non-proliferation. We work together in G20. We are determined to actively assume roles in other international economic and political initiatives. In this field, too, we are going to increase our cooperation with Japan.[20]

It remains to be seen to what extent the goals mentioned by Davutoğlu can and will be achieved, but it is nonetheless striking how Turkey’s vision of China and Japan differ in issues that are not related to economics.

Turkey’s relations with Korea exhibit a similar pattern to those with Japan in the sense that political relations are marked by congeniality, whereas economic relations are defined by an increasing trade deficit for Turkey. In 2012, Turkey’s trade with Korea amounted to $6.0 billion, with $332 million of exports and $5.7 billion of imports. Over the period 2000 to 2012, Turkey’s trade with Korea increased 4.6 times. In the meantime, similar to Japanese corporations, starting in the late 1980s and early 1990s Korean corporations like Hyundai, LG, and Daewoo established joint ventures with local partners and commenced production in Turkey. These ventures export most of their production; for instance, it is said that 75 percent of Hyundai’s output in Turkey is destined for exports. However, similar to the Japanese case there has been a slowdown in investment flows from Korea to Turkey.

An important step taken in Turkish-Korean relations is the signing of a free trade agreement in August 2012. This agreement is the first of its kind that Turkey has signed with an East Asian country, and it is expected to lead to a relative narrowing of Turkey’s deficit vis-à-vis Korea by providing Turkish exporters with rights and opportunities equal to American and European contributors. Similarly, thanks to initiatives supported at the level of the president and prime minister, it is possible that Korean companies will increase their investment in Turkey. It must be noted that while Turkey desires more trade with and more investment from Korea, at the political level the Turkish government has so far expressed little interest in aligning its policies with those of Korea in regard to issues of global governance. In this field, Turkey’s foreign policy is more in line with that of Japan.

Southeast Asia is one of the regions on which Turkey’s “new” foreign policy paradigm focuses. The tsunami disaster in 2004 marked a kind of turning point in terms of this focus, as Turkish leaders made visits to the region and brought aid and supplies, and Turkish NGOs poured into the disaster-stricken countries to contribute to relief efforts. As the main pillar of Turkey’s changing foreign policy, economic relations are at the forefront of Ankara’s initiatives toward the region. However, recent developments in Turkey’s relations with the region show two important themes. One is the emphasis on humanitarian assistance and mediation efforts, and the other is the Islamic connection.

Turkey’s humanitarian assistance and relief efforts, aimed at increasing regional and global influence, are undertaken through several channels, including public institutions such as the Turkish Red Crescent and NGOs. A recent example is the assistance provided to Myanmar to help the victims of sectarian violence in Rakhine State. Erdoğan and Davutoğlu personally visited Rakhine to supervise the efforts. Moreover, Turkey has also taken initiatives with the UN and the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC) to increase the world’s attention on Myanmar.

This new foreign policy approach positions Turkey as a mediator between parties in issues of conflict. A statement on the Turkish Foreign Ministry’s website states that mediation is the most efficient way of solving international problems, noting that it can reduce the likelihood of conflict and strengthen the base for peace and stability, thus “facilitating the environment of cooperation based on mutual benefits that Turkey wants to establish.” So far Turkey has assumed a mediation role in several regions, though all have been in the country’s near neighborhood or are a specific foreign policy priority.[21] A recent case, however, shows that Turkey’s mediation efforts are now reaching Southeast Asia. Turkey has taken part in the UN’s International Contact Group for the Philippines, which facilitated the negotiations between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. These negotiations helped to bring about a preliminary agreement that is likely to pave the way for an end to the decades-long militant insurgency in the country.

In addition, in both Myanmar and the Philippines, Turkey’s interventions have had an Islamic connection, that is, both were in regard to an Islamic minority in each country. While it would be unfair to assert that Turkey only provides assistance to Muslims around the world, and while it would also be incorrect to argue that Islam has become a defining factor of Turkey’s foreign policy, shared faith can and does build connections between peoples, thus facilitating relations between countries. While Turkey does not see Southeast Asia through the prism of Islamic solidarity only, Islam provides a crucial way in which to engage some of the countries more effectively. It is therefore no surprise that the Southeast Asian country with which Turkey has so far the strongest relations is Indonesia, that is, the country with the world’s largest Muslim population. Recent overtures made by Ankara have also been directed toward another Muslim majority state, Brunei.

Greater influence in the international arena cannot be achieved through bilateral relations only; hence one of the defining features of Turkey’s changing foreign policy is greater activism in multilateral platforms.

Turkey’s Activism in Asia at the Multilateral Level

Turkey is a member of NATO and a candidate for EU accession. In the meantime, the country is increasingly active in other platforms to increase its global standing. These platforms also enable Turkey to cooperate with Asian countries on common regional and global issues. The G20, which brings together the world’s major economies to work on global governance, as well as organizations such as the OIC and the Developing-Eight (D8), which bring together Muslim-majority countries, offer venues for Turkey to collaborate with Asia. Two other regional organizations with which Turkey has recently been associated, however, underline its interest in institutional involvement in regional issues concerning Asia.

Turkey became party to ASEAN’s (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in July 2010, and is now targeted to become a dialogue partner of ASEAN. The organization is the most comprehensive structure covering Southeast Asian nations, and it also engages Asian economic powerhouses like Japan, China, and Korea through such offshoots as the ASEAN+3.

Turkey’s involvement in Asia’s multilateral platforms in the political/security sphere is realized through the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA), an intergovernmental organization aimed at enhancing cooperation in order to promote peace, security, and stability in Asia. Turkey held the chairmanship of the organization between 2010 and 2012.

It should be noted that this strengthening of relations with Asian countries is acting as an incentive for the increase in academic programs on Asian languages and Asian studies in Turkey, which in turn help to further improve relations. For instance, Japanese language programs are now found at eight universities, including Ankara University and Boğazici University. Since 2007, Confucius Institutes have been established at Middle East Technical University, Boğazici University, and more recently, Okan University. These institutes complement the establishment of graduate programs in Asian Studies, such as the most recent one, founded in 2012 at Boğazici University. Whereas Japanese language study has been more popular than Chinese or Korean language study, Chinese and Korean are catching up, with Chinese somewhat more popular.[22]

In brief, Turkey is now more involved in Asia than ever before, and it continues to pursue and improve this involvement through both bilateral and multilateral channels. Once only looking toward the West, Turkey is now heading in several directions, with Asia a major area of interest. Does this development mean that, having lost its faith in being a part of the European community, Turkey is now becoming a part of the Asian community?

Turkey as a Bridge

It is clear that as Turkey’s foreign policy paradigm is evolving into a more dynamic, assertive, and multidimensional form, Asia’s place in Ankara’s foreign policy vision is growing substantially. Yet this does not necessarily indicate that Turkey is turning its back on the West. The EU accession remains the main axis of Turkey’s foreign policy and relations with the West, and Western ideas are embedded not only in the country’s institutions, but also in people’s minds and their ways of living. This was what Erdoğan meant when he said in 2010 that “from the geographical point of view Turkey is placed on both Europe and Asia, but there is no doubt that from the cultural perspective Turkey is European.”[23] While full membership in the EU does not appear in sight, this absence of institutional belonging does not necessarily imply the absence of ideational belonging.

What we can state for the moment is that Turkey is becoming a good and reliable partner for Asian countries. Turkey is not part of the European community nor is it part of the Asian community, but Turkey is becoming an increasingly influential member of the global community. With its evolving foreign policy approach, Turkey has given up its overemphasis on the West and has begun to form close links with all parts of the world, Asia being high on the priority list. For decades Turkey has claimed to be a bridge between the West and the East, between Europe and Asia; at last Turkey is turning the bridge analogy from rhetoric into reality.

This contribution is part of the Middle East-Asia Project at the Middle East Institute.

[1] Bülent Aras, “Davutoğlu Era in Turkish Foreign Policy,” SETA Policy Brief 32, SETA Foundation (Ankara), May 2009.

[2] Philip Robins, Suits and Uniforms: Turkish Foreign Policy Since the Cold War (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2003).

[3] Altay Atlı, “Businessmen and Turkey's Foreign Policy,” International Policy and Leadership Institute (Paris), 2011.

[4] Kemal Kirişci, “The Transformation of Turkish Foreign Policy: The Rise of the Trading State,” New Perspectives on Turkey 40 (2009): 29-57.

[5] In this essay, the terms “Asia” and “Asian countries” are used to denote East, Southeast, and South Asian countries unless stated otherwise.

[6] All of the bilateral trade figures used in this essay are obtained from the Turkish Institute of Statistics (TÜİK).

[7] All of the investment figures used in this essay are obtained from the Turkish Undersecretariat of the Treasury.

[8] Figures are obtained from various statements released by the Prime Minister’s office.

[9] Turkish citizens (holders of ordinary passport) can travel to Japan, Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, Macau, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Maldives without a visa. Travellers to Indonesia and Cambodia can obtain visa stamps at entry points. See the Turkish Foreign Ministry website at http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turk-vatandaslarinin-tabi-oldugu-vize-uygulamalar….

[10] Turkey has recently opened an embassy in Naypyidaw (Myanmar) and a consulate general in Guangzhou (China). In the meantime, Singapore and Sri Lanka opened embassies in Ankara.

[11] Yunus Emre Foundation web site, http://www.yunusemrevakfi.com.tr/turkiye.

[12] Altay Atlı, “The Future of Turkey’s Relations with China,” Turkish Review 2, 6 (2012): 96-101.

[13] Atlı, “The Future of Turkey’s Relations with China.” For example, when then Vice President of China, Xi Jinping, visited Ankara in February 2012, a group of Uighur activists attempted to demonstrate in front of his hotel. Turkish police dispersed the group and before Xi left the hotel.

[14] “Erdoğan: Adeta Bir Soykırım,” Milliyet, 11 July 2009.

[15] “Erdoğan, Esad’a Arapça Yüklendi,” Milliyet, 7 February 2012.

[16] As stated in a recent report by the Turkish-Japanese Business Council, “The most important aspect of economic and commercial relations between Turkey and Japan is the Japanese investment in Turkey. This is because the activity of Japanese companies in our country in their respective fields of activity do not matter only in terms of investment, but they also and directly influence trade relations with our country and the variety of products and commodities that are subject to trade.” “Japonya Ülke Bülteni,” DEİK, March 2012.

[17] “30.06.2013 Tarihi İtibariyle Türkiye'de Faaliyette Bulunan Yabancı Sermayeli Firmalar Listesi,” database accessible through the Ministry of Economy website, http://www.ekonomi.gov.tr.

[18] “Japonya Ülke Bülteni.”

[19] Altay Atlı, “Cumhurbaşkanı Gül’ün Japonya ziyareti ardından,” Referans (Küresel Supplement), 3 April 2008.

[20] Transcript of the press conference held by Davutoğlu and Gemba on 6 January 2012 is available on the website of the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs: http://www.mfa.gov.tr/japonya-disisleri-bakani-gemba-ulkemizi-ziyaret-e….

[21] Turkey has undertaken mediation efforts, with varying degrees of success, in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, Bosnia, and Somalia.

[22] University students who study Japanese can be estimated to number around one thousand.

[23] “Erdoğan’ı Bıktıran Türkiye Yorumu,” Milliyet, 1 July 2010.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.