A new identity or more security

For a long time now, Iran has declared that its political identity is contrary to that of the Western world. Its leadership has articulated an interest in maintaining commercial and technological relations with Western countries, but when it comes to politics and culture, all decisions and operations are molded by local tradition and mired in inertia. Though conventional wisdom considers ideology as the root cause of this division, an alternative explanation is that it actually reflects security concerns that align with Beijing’s and Moscow’s own considerations. Political integration with the West, and particularly the United States, would undermine the state’s grasp on society, challenge the narratives of its elites, and hollow out its cultural traditions. Fear of overwhelming American and European soft power by the top echelons of such states is thus an essential factor in their decision to differentiate between commercial and non-commercial relations with Western countries. Consequently, to ensure a tighter grip on domestic control in China, Russia, and Iran, keeping the United States at bay is a priority for regime security.

Iran’s reinvigorated relations with China and Russia over the last decade are far less about identity and more a reflection of short- to medium-term security concerns. The pivot to the East is therefore politically motivated. The pivot also cultivates the distance theory about the West, resonating with the policy of absolute sovereignty and economic self-sufficiency that many Asian and African countries pursued in the aftermath of decolonization in the 1960s. In a deeply integrated international order, this attitude is an anomaly. For example, India’s membership in BRICS (a grouping of emerging economies comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is intended to expand its hedging capabilities as well as its bargaining opportunities not only in security but also in commerce, technology, foreign direct investment (FDI), and trade. This calculation may well be applied to understand the decisions by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and other developing countries to join BRICS too. Given the fractured and factionalized nature of BRICS, Iran appears to belong to the camp that fears Western dominance.

BRICS: A political temperament

BRICS, like the SCO, seems to be more of a reflection of a political temperament than a structure for building consensus and collective action. Both organizations are fundamentally shaped by Chinese and Russian political motives to project power outside of America’s global reach, however ceremonial and ineffectual that may be. Neither organization enjoys internal harmony and commonality of purpose among its members. According to one assessment, while China and Russia pushed for Iran’s BRICS membership, India and Brazil were apprehensive about the move, worrying that the grouping might appear too anti-American. The most visible standoff within both organizations is between India and China. While a member of these China-led organizations, India is also a key participant in the American-led Quad that includes Japan and Australia. India is one of the four members of the I2U2 grouping as well, alongside Israel, the UAE, and the U.S. Both the Quad and I2U2 are comprised of like-minded members. One recent indication of the disharmony within BRICS was China's issuance of a condemnation of retired Indian military officials over a visit to Taiwan, complicating an already difficult relationship that dates back to the 1962 border clashes.

It is inconceivable that BRICS could act as a counterweight to American-built institutions like the G7 and G20 given India’s and South Africa’s wide-ranging partnerships with the West and in particular with Washington. Over the years, the United States has been able to manage 52 military and political alliances in the international system. With India’s and South Africa’s overlapping commitments and vast opportunities for hedging and bargaining, the predictability of their behavior within BRICS will be opaque at a minimum. In other words, their close alignment with Europe and the United States means they do not have a free hand to converge with the anti-Western policies of Russia and China. Therefore, the heterogeneity of BRICS is sufficient proof of its political ineffectiveness. Aside from Russia, all of its members have deep interdependencies with the United States and cannot go too far in disrupting the American-led global order. Setting aside questions about its practicality, BRICS members do not have a consensus on de-dollarization. With Chinese capital controls and restrictions on currency convertibility, it is not clear that the renminbi can effectively serve as a medium for international foreign exchange transactions. One analyst even dubbed the U.S. dollar the “oxygen of the global economic system.”

BRICS membership without relations with the West

In this context, the main dilemma when it comes to Iran’s participation in these two organizations is that Tehran does not have normal relations with Western countries, particularly with the United States. Its membership underscores Tehran’s desire for political inclusion and its intention to dissuade those who argue Iran is an isolated country. Membership in the SCO and BRICS cannot alter Tehran’s economic woes as U.S. secondary sanctions place enormous limitations on Iran’s economic interactions with other states. The fact remains that Iran is not a signatory of the Foreign Action Task Force (FATF), and its international financial transactions do not and cannot operate according to global procedures and standards. Membership in BRICS will not change this. Short of normalization, Iran pursues a consistent policy of de-escalation with the United States and increasingly with its Arab neighbors. The fundamental motive for these changes is to overcome its economic malaise. Economic mismanagement compounded by U.S. sanctions results in formidable economic and social insecurity for the leadership.

The recent unwritten modus vivendi with the United States can be interpreted exclusively as a function of Tehran’s economic and financial crises. This “understanding” is also in line with a consistent policy of the Islamic Republic regarding Washington: no normalization and no confrontation. No normalization because U.S. demands cannot be met since they will disrupt the status quo and power structure in Iran, and no confrontation because it is a losing strategy. Alternatively, as the foundation of regime security doctrine dictates, Middle Eastern proxies are cultivated as a deterrent force to keep the United States at bay. While addressing members of the Experts’ Council on March 10, 2022, Iran’s supreme leader established a correlation between regional presence on the one hand, and power and solidity of the polity (nezaam) on the other. Ultimately, transactional predispositions in Iran’s foreign policy aim to boost its foreign revenues to address economic problems like the shortage of funds, budget deficits, unrelenting government spending, and runaway inflation.

In addition to the historical structural malfunctioning of Iran’s economic system, the country currently suffers from two acute difficulties: a shortage of foreign reserves and the almost non-existence of foreign investment. Both problems are exacerbated by U.S. sanctions. Given the current personalities and policy agenda, there are no prospects of a paradigm shift in the country’s foreign policy. Transactional approaches to problems have repeatedly been the solution to somewhat ease financial crises in the short to medium term. BRICS is no panacea for the underlying conundrums in Iran’s economy. Recent arrangements with Washington serve interests on both sides: Iran’s access to petrodollars expands, additional oil is supplied to global energy markets (through expanded Iranian and Venezuelan oil production), American prisoners are released, U.S. military forces in the region remain safe, Tehran’s nuclear program slows down with greater International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) digital surveillance, Arab-Iranian tensions are de-escalated, and Iran can be removed momentarily from the radar of American domestic politics. Of all of Iran’s regional sources of asymmetric leverage, Yemen is the least strategic. It is no wonder that Iran was willing to swap its influence in Yemen in return for reduced Saudi financial and logistical support for Iranian opposition groups. This is yet another example of Tehran’s transactional dealings. At this time, both sides are testing intentions and are involved in a process of verification, cascading implications, and potential positive spillover effects.

A foreign policy without strategic partners

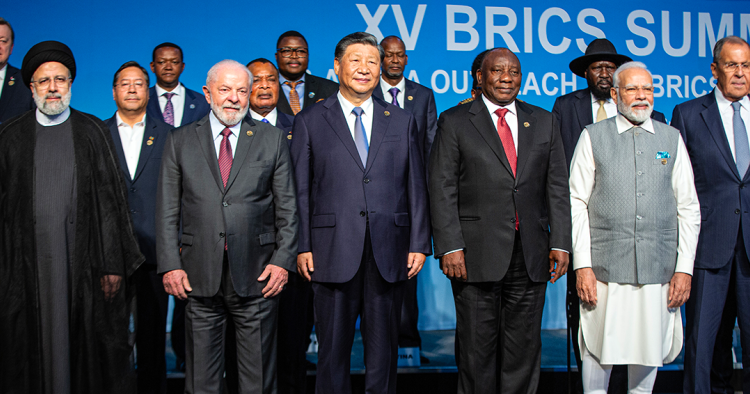

Iran’s recent understanding with Saudi Arabia and the United States embodies an essential feature of the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy — that it is a lonely state and for the moment is incapable of cementing strategic relations and alliances with other countries. This feature is both intentional and methodically framed and managed. Any type of strategic alliance, it is thought, will only result in dependencies that may eventually rein in the deep state’s ability to maneuver. Unless and until Tehran decides to engage in a foreign policy shift, the current complications and instabilities will endure. The causal relationship between Iran’s foreign policy and its economic crises is barely debated in the country. In neighboring Iraq, it took some 13 years for the United States to remove sanctions. In this context, membership in BRICS provides only psychological satisfaction for Iran’s leadership by enabling it to rub shoulders with great powers, providing photo-ops with leaders of other countries, and giving it a platform to project visibility and public relations in foreign policy.

Iran may be under the delusion that through BRICS membership, it is contributing to a different world order that will disrupt Western hegemony. Furthermore, Iran may also think that Moscow and Beijing are somehow promoting “new thinking.” In reality, China, whose share of BRICS’ GDP is about 70%, is seeking an enlarged domain to exercise power and influence and a greater share of decision-making. Power prevails over ideas and ideology. If Beijing reaches its ambitious target of adding 18 members to BRICS, its share of the group’s output would be a hefty 47%, compared to America’s 58% in the G7. All members of BRICS can only prosper within the corridors of the contemporary international system. As The Economist put it recently, “It would mean [then] that although the BRICS could criticize the Western-led international order with a louder voice, they would struggle even more to articulate an alternative.” It is noteworthy that neither Moscow nor Beijing supports the other party’s proposals for reforms in the United Nations, implying that they prefer to preserve the current global hierarchy. One issue that Iran fails to pay attention to and can be understood as a form of cognitive dissonance is the reality that China operates within the international capitalist system and its second ranking in the global economy is indebted to the capitalist order. Iran’s membership in the SCO and BRICS resembles a football player who is always benched and never gets a chance to play. In this political context, Iran will have to watch from the sidelines how China, Russia, and the United States operate in the field.

The accuracy of Iran’s claim that its membership in BRICS is a “historic achievement” can be gauged by how much FDI it receives from other members of the organization. Given massive European and American sanctions on Iran’s banking and economic institutions, it is unlikely that private or state enterprises would be willing to risk their operations in the Western world. Perhaps, Iran’s ultimate aim is to seek a supporting global political alternative like BRICS not to succumb to American power and the U.S. dollar. Yet, these ostentatious manifestations of its search for alternative sources of power and security provide no foundation for tangible economic benefits. Without normal relations with the West, Iran’s membership in BRICS cannot deliver benefits in the form of trade, FDI, higher economic growth rates, or technology transfer in key areas like artificial intelligence. As long as Iran’s foreign policy prioritizes security over national economic development, participation in organizations under an exclusive Russian and Chinese umbrella will only uphold the status quo in the country.

Mahmood Sariolghalam is a non-resident scholar with the Middle East Institute’s Iran Program.

Photo by Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.