The Hirak — Algeria’s recurring Friday protests asking for fundamental change — is now a year old. Neither meaningful change nor unabashed repression proceeds from the Algerian administration. Meanwhile, protestors struggle to find an authentic and compelling leadership.

The European Union (EU), its closest territory only 150 km away, has responded in measured terms. On Nov. 28, 2019, a European Parliament resolution criticized the Algerian administration’s arbitrary and unlawful arrest of protestors and called for the release of those imprisoned for exercising their right to freedom of expression. The resolution also called for a peaceful and inclusive political process.[1]

While the practical effect of this resolution is imperceptible for now, it is notable that the EU’s calls for democratic reform are framed in economic terms that emphasize the benefits of greater economic integration between the states of the Maghreb. Signaling its practical intentions for social justice, the EU is attempting to walk a fine line between upholding its democratic values, which includes respecting the will of the Algerian people, and maintaining its relationship with an Algerian administration sensitive to external criticism.

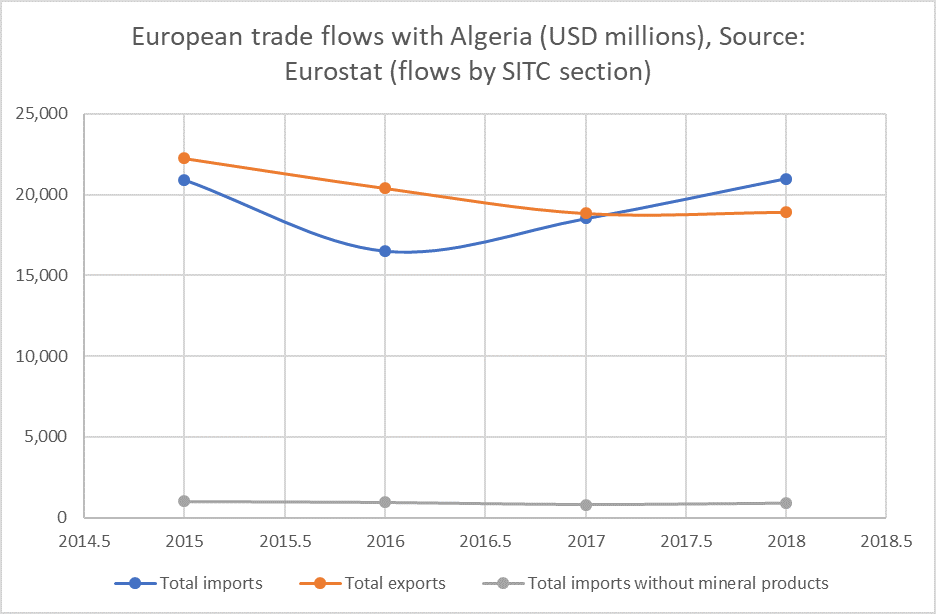

The EU has reason to be cautious. Today, trade between the EU and Algeria is worth around $50 billion,[2] the largest figure for North Africa. If meaningful economic and political change is managed in Algeria, the possibilities for enhanced trade and economic integration are enormous. However, if things go badly in its transition, the consequences are likely to be dire for Europe, in terms of both its interests at home as well as those in the Maghreb and Africa.

So, what opportunities do the ongoing changes in Algeria present for enhancing economic integration in the long term?

Algeria in Europe

To answer this question, it is useful to look first at the economic history of the Algeria-Europe relationship.

Algeria was part of the birth of a modern united Europe. Under the French colonial regime, Algeria’s territory was designated as three départements of France. As such, in 1957, despite being in the midst of a war for independence from France, Algeria automatically became part of the European Economic Community (EEC) with the signing of the Treaty of Rome. (By the same token, it also became part of NATO in 1949.)

On achieving independence in 1962, Algeria exited the EEC (and NATO) and distanced itself from Europe. The enormous trauma of the war of independence and the experience of colonialism as a whole contributed to Algeria’s deep aversion to international interference in its domestic affairs. France’s refusal to admit full culpability for its colonial past in Algeria remains a sensitive issue and a sticking point in bilateral relations, albeit one that that President Emmanuel Macron is doing more to address than any previous French leader.[3]

The first half of the 20th century saw Algeria closely entangled, often in involuntarily and challenging ways, with Europe and the birth of the European Community. Upon independence, Algeria undertook an ambitious development and industrialization agenda and, active within the Non-Aligned Movement, sought to break out of an economic order dominated by rich industrialized countries, including those of Europe.[4]

Post-independence, relations with Europe progressed modestly. In 1976, the EEC-Algerian Cooperation Agreement was signed to offer financial assistance and support in training business executives and constructing infrastructure. It is widely thought that this agreement yielded disappointing results, but it represented the beginning of something of a more equitable relationship between Algeria and Europe.

Barcelona and beyond

During the Cold War, Algeria maintained close economic ties with the USSR, and Russia’s continuing predominance in arms sales to Algeria is a legacy of this relationship. However, with the end of the Cold War, a number of diplomatic overtures accelerated Algeria-Europe integration efforts. The 1995 Barcelona Declaration, which started the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership, initiated negotiations for an Association Agreement. This eventually came into effect in 2005 and remains the most important agreement governing EU-Algeria relations.

In 2008, the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) was formed to promote outreach and cooperation between the EU and its Mediterranean neighbors. Algeria’s engagement with the UfM has been relatively limited, given the country’s economic stature and geographic centrality in the region. Part of the reason for this is the challenges presented by Arab-Israeli relations within the UfM.

When the Association Agreement came into effect, the EU eliminated tariffs on most Algerian exports, while Algeria was allowed to keep in place temporary customs duties to protect national industries, with a phase-out period of 2005-17. However, in 2017 the deadline was extended to 2020, and to date this issue has not yet been resolved.

These agreements are aimed at deepening what is now a multi-faceted relationship. Europe and Algeria agreed upon official shared priorities for 2016-20 in the areas of economic development, integration and trade, security and strategy, energy and environment, dialogue and governance, migration and culture. It is the economic and integration field that is at the very center of Europe’s diplomatic efforts toward Algeria.

European ambitions for liberalization

The EU sees great potential in Algeria’s economy, which is the largest in the Maghreb with a total GDP of $167 billion in 2017.[5] It also sees an underdeveloped and stifled private sector and unattractive foreign direct investment prospects. Most worrisome is the heavy reliance of the economy and the Algerian state’s rentier model of governance on the hydrocarbon sector, which exposes the country’s general stability to oil price shocks. Today, the long-term impact of the 2014 shock, when oil prices fell by almost half, can be seen in the Hirak’s call for a fundamental overhaul of the social and political contract.

In broad terms, the EU’s integration efforts have a few interlocking aims and approaches. The EU finances a range of programs for various economic sectors to encourage diversification beyond hydrocarbons, to bolster economic performance, and to improve the business environment. As an incentive to make such changes, the EU offers financial assistance through the European Neighborhood Instrument (ENI) and the Emergency Trust Fund.[6]

Integration’s slow progress

When it comes to integration and market liberalization, Algeria has moved cautiously. For instance, the Association Agreement, which came into effect in 2005, requires an action plan from Algeria laying out how the country will liberalize its markets. This action plan has yet to be submitted. Algeria’s policy around hydrocarbon liberalization is emblematic of its stance. The combination of the 2005 Hydrocarbons Law and the ensuing Presidential Order 06-10 of 2006 was a mixed bag for hydrocarbon liberalization, allowing international companies to carry out exploration and exploitation, but ensuring that Algerian national oil company Sonatrach retains a minimum 51 percent share.[7]Until recently, this ownership ratio was also required for the formation of any company in Algeria, but the 2020 Finance Law has limited the scope of this measure to “strategic” activities.[8] The overall protectionist thrust of these developments in the past 15 years has contributed to the World Bank ranking Algeria 157th out of 190 countries in its 2020 Doing Business report, placing it between Guinea and Micronesia.

EU support is conditioned to a great extent on political and economic liberalization. As a result, Algeria has received little financial assistance from the EU compared to its neighbors in the Maghreb. In the 2007-17 period, Algeria received an annual average of €61.4 million in assistance compared to €698.5 million for Morocco and €454.8 million for Tunisia.[9]

The effectiveness of Europe’s efforts to help diversify the Algerian economy and support the development of the private sector is open to critique.[10] An underlying assumption of the EU’s approach is that lowering trade barriers for Algerian goods will aid the growth of private small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in non-hydrocarbon industries by allowing them access to new markets in Europe. This growth is intended to stimulate the diversification of Algerian exports away from its longstanding reliance on hydrocarbons and to encourage the expansion of the private sector. However, while Algerian exports into Europe have grown in aggregate since trade barriers were lowered, most of this growth has come from the export of mineral products, including oil and gas. Such commodities are sold by large state companies rather than private SMEs. On this basis, EU integration efforts are accused of doing more to solidify Algeria’s economic composition than to diversify it.[11]

Compared to its North African neighbors, Algeria has not benefitted from as strong a growth in exports to Europe since the Association Agreement came into effect, even while European exports have done relatively well in Algeria. This disparity in trade performance contributes to the lukewarm attitude on the part of the Algerian administration toward integration, as does its aversion to the loss of import tariff revenue. Moreover, the Algerian administration appears unlikely to relinquish majority control over the hydrocarbon industry, which is its primary source of income. Right now, during the current period of mass mobilization, the administration feels especially sharply the need for control over income streams.

Mass mobilization creates uncertainty for integration

Overall, the process of Algerian-European integration has been deliberate if somewhat sluggish in comparison to neighboring states. The process has been slowed by the current period of massive mobilization, which has provoked very generally a strategic response of caution from the administration.

Movement on integration has not stopped them completely, however, and indeed has thrown one development into sharp relief. As 2019 became 2020, the Algerian administration passed new hydrocarbon legislation intended to improve opportunities for foreign investment in the hydrocarbon industry.[12] This move proved unpopular with sections of the Hirak, which criticized the new law as an attempt by the administration to secure foreign backing. The law has also been criticized as illegitimate on the basis that it was passed by an interim president who arguably lacks the authority to do so.[13] Although these criticisms appeared to have had little effect for now, the EU may well expect popular voices to be another variable in negotiations around integration.

For now, it appears that the Hirak’s opposition to the hydrocarbon law is based on political circumstances, rather than economic principles. It would be rash to attempt to generalize the Hirak’s economic ideology or attitude toward economic integration with Europe. What can be said with confidence is that many Algerians are looking for a significant change that will address the current difficult economic conditions, where youth employment has reached 30 percent and living costs have outstripped the wages of those who have work.[14]

Risks and opportunities

From a short-term point of view, the Hirak is a headache for economic integration. However the discontent and demand for better economic performance is actually a very important opportunity for EU-Algeria integration. While its demands and ideological outlook are certainly not homogenous, the Hirak is demanding an economic transformation and the end of grand and petty corruption.[15] This could well open the way further for market reform and anti-corruption measures supported by the EU. Such potential responses could well be supported technically by the EU and would also represent avenues for furthering economic integration efforts.

In an Algerian transition, there are certain pitfalls to be avoided, well illustrated by examples in the region. The first is the danger of one-size-fits all liberalization programs led by international financial institutions. In the case of Egypt, by reducing social welfare in various forms, including fuel and food subsidies, such programs contributed to the yawing wealth gap and undermined stability in the medium and long term.[16] For its part, in the mode of tailored liberalization, Europe might take the opportunity of Algeria’s ongoing transition to reflect inwards. The Common Agricultural Policy has deleterious effects on the competitiveness of African agricultural goods in Europe and elsewhere.[17]

The second risk is that the continuing programming actually solidifies the reliance on hydrocarbons rather than helping to diversifying production.

In addition to the opportunities presented by the market overall, other, more specific opportunities can be envisaged. The development of Algeria’s green energy industry is both an opportunity for integration and an energy security imperative. While Algeria struggles to maintain energy exports and supply growing domestic demand, Europe’s need for green energy will also increase. A flourishing green industry would provide new private sector jobs that will be needed to compensate for a possible contraction of the Algerian public sector.

Support for the green energy sector is already being pursued through such projects as the German Algerian-Energy Partnership.[18] However, there are two distinct challenges to overcome: the weakness of green financing in Algeria, and the administration’s tendency to favor non-renewables. If the more environmentally-conscious Algerian youth can help bring green energy concerns to the fore, Europe may have more room to maneuver. In addition, Algeria could leverage its particular vulnerability to climate change as part of an effort to garner more international support in this area.

A successful transition in Algeria may also create an opportunity for greater economic integration within the Maghreb. Despite the early hopes for the Arab Maghreb Union, Algeria’s integration with its neighbors is very limited. This is in part the result of the poor diplomatic relations between Algeria and Morocco. Anecdotal evidence suggests a popular sense of solidarity within the Maghreb that points to rivalries between ruling elites as the major stumbling block. A sense of renewed political identity in Algeria could produce fresh momentum to pursue intra-Maghreb integration, a project in which Europe could play a supporting role.

Indirect, or non-economic, routes to improved economic integration are also available for development. One is education and the political culture influence it brings. Europe enjoys a relatively high level of popular support in Algeria: a 2017 public survey put Europe as the favorite foreign policy partner for the country.[19] According to this survey, when it comes to the relationship with the EU, Algerians are interested most of all in cooperation in the spheres of education, culture, and science. Already pursued by the EU and Algeria, such forums of interaction facilitate relationships that will be useful in the long term for trade and integration. Algeria is entering a period of popular political renewal and as such has a new need for political organization and governance skills, as well as international political networks. Now would be an opportune moment to expand Europe’s educational engagement with Algeria. As Beijing increases its soft diplomacy in the field of education by offering academic scholarships for study in China, the moment to compete for Algeria’s political culture and the sympathies of its youth is now.

Uncertainty and a future in the making

For the time being, Algeria’s transition offers more uncertainty for the process of integration than anything else. The stalemate between the Hirak and the administration continues. Indeed, with the current political situation, Europe’s space for directly engaging with the Hirak’s cause or on its own integration goals is very limited. Explicit European support for a revolution may do something to progress the Hirak’s cause but would critically narrow the relationship with the Algerian administration and thus endanger the threads of support to democratic transition that Europe does provide.

As such, Europe will need to continue balancing its rhetoric and policy toward Algeria in a way that upholds its values but remains realistic about its economic ties and remains politic in terms of the balance of power in the country. The Algerian administration is focused inwards, and in the meantime, integration is on hold. However, some sort of change, and with it, opportunity of one type or another, will come. This article’s suggestions work largely from the known and established parameters of the Europe-Algeria relationship. However, this outlook must be augmented by an avowal of the potential the current period uncertainty. The best use of the EU’s efforts during this period of charged limbo would be to work on scenarios and prepare for them, using a forward-looking approach that brings together Algerians and Europeans of different disciplines to think creatively about the future of the bilateral relationship. If the EU and Algeria can be creative and act with foresight, then when it comes to writing future history, the Hirak era will outshine the Barcelona period.

Alex Walsh is an independent researcher and consultant in governance and security in the Middle East North Africa region. He has worked in security sector reform and peace building programs in Tunisia, Lebanon, and Jordan. He is a coordinator on the Algerian Futures Initiative, a foresight project looking at scenarios for 2030. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Kay Nietfeld/picture alliance via Getty Images

Endnotes

[1] European Parliament resolution of November 28, 2019 on the situation of freedoms in Algeria (2019/2927(RSP) http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2019-0072_EN.html.

[2] In 2017, the total value of trade stood at $44.6bn, per OEC figures.

[3] Yasmeen Serhan, "Emmanuel Macron Tries – Slowly – To Reckon with France’s Past," The Atlantic, September 14, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/09/emmanuel-macr….

[4]Hamza Hamouchen, "Algeria, an Immense Bazaar: The Politics and Economic Consequences of Infitah," Jadaliyya, January 30, 2013, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/27927.

[6] European Commission, "European Neighbourhood Policy And Enlargement Negotiations: Algeria," https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/neighbourhood/countries/algeria_en.

[7] "The Algerian Hydrocarbons Regulations - Energy and Natural Resources - Algeria," accessed February 28, 2020, https://www.mondaq.com/Energy-and-Natural-Resources/86988/The-Algerian-….

[8] Baker McKenzie-Richard Mugni et al., "Algeria 2020 Finance Law | Lexology," accessed February 28, 2020, https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=aeeab803-c161-45f8-97a7-….

[9] These amounts are for the period 2007-2017 and an average for this period is given, figures provided by EU Aid Explorer.

[10] Daniela Caruso and Joanna Geneve, "Trade and History: The Case of EU-Algeria Relations," February 17, 2015, https://www.bu.edu/ilj/2015/02/17/trade-and-history-the-case-of-eu-alge….

[11] Daniela Caruso and Joanna Geneve.

[12] “Under the new legislation, the tax burden on state-owned Sonatrach and its international partners will be cut from 85% to around 60%-65%.” "Algeria’s New Hydrocarbon Law Comes into Force amid Output Slump | S&P Global Platts," January 6, 2020, https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-….

[13] Simon Speakman Cordall, "Algeria’s hydrocarbon reform adds fuel to protest movement," November 7, 2019, Al Monitor, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/11/algeria-protests-hyd…

[14] “Living costs have become prohibitively high for the middle classes in recent years. The average monthly wage is around 30,000 dinars (€225), but it costs 50,000 dinars (€373) to rent a three-bedroom flat in Algiers.” Khelaf Benhadda, "Social and economic woes weigh heavily on Algeria’s future," November 6, 2019, https://www.equaltimes.org/social-and-economic-woes-weigh?lang=en#.XhOH….

[15] The prevalence of corruption works at grand and quotidian levels, permeating everyday life for Algerians. The Arab Barometer’s 2019 public survey found that 56% of Algerians consider it necessary or highly necessary to pay a bribe to access healthcare, while 45% felt the same way about education. Arab Barometer V, “Algeria Country Report,” August 26, 2019. https://www.arabbarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/ABV_Algeria_Report_Pub…

[16] Mohammed Mossallam, "The IMF in the Arab World: Lessons Unlearnt," SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, November 1, 2015), https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2705927.

[17] Ian Mitchell and Arthur Baker, "New Estimates of EU Agricultural Support: An “Un-Common” Agricultural Policy," Center for Global Development, November 21, 2019, https://www.cgdev.org/publication/new-estimates-eu-agricultural-support….

[19] Abdennour Benantar, "Algeria and the European Union: Uncertainties of a Dense Relationship," Euromed Survey, Euromesco Paper, October 2017, https://www.euromesco.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/200610-EuroMeSCo-P….

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.