Africa is a rising “multipolar continent” where established and emerging extra-regional powers are vying for commercial gain and geopolitical influence. Turkey has figured prominently in this third surge of foreign interest in Africa.[1] Rooted in a redefinition of the country’s role in international affairs and a convergence of interests between state and business elites, Turkey has developed an increasingly dense network of ties across multiple dimensions throughout Africa.[2]

The growing business volume of Turkish companies in African construction markets is illustrative of the progress Turkey has made in securing a strong foothold on the continent. Although Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are by far Africa’s biggest builders,[3] Turkish construction companies have established themselves as capable and competitive players not just in the Maghreb but in Sub-Saharan markets as well.

The Turkish construction industry expands abroad

Turkey’s construction and contracting industry has been at the forefront of the country’s economic development. The sector accounts for about 6% of the overall gross domestic product (GDP) and employs 1.5 million people. Its share of the overall economy is nearly 30% when factoring in the direct and indirect impacts on related industries such as construction machinery, building materials, engineering, and architecture.

It has been five decades since Turkish contractors entered the global market. In 1972, Libya became the first country to which Turkish contractors exported their services.[4] Between then and April 2022, Turkish construction firms implemented 11,243 projects in 131 countries with a total project value of $435 billion.[5] With 40 firms among the top global companies, based on revenues generated from overseas projects, Turkey placed third after China (78) and the United States (41) in the Engineering News-Record (ENR) 2022 Top 250 International Contractors list.[6]

Over the years, the pursuit of business opportunities in foreign markets by Turkish companies has been both a growth and a risk mitigation strategy, spurred by stagnant domestic market conditions and fortuitous circumstances as well as by unforeseen adverse developments in the markets of operation.[7] On several occasions, severe economic contractions and resulting bottlenecks in the domestic construction sector have impelled Turkish contractors to concentrate more on business abroad. This was the case in the early 1970s, when the depressed home market coincided with the booming demand for construction services in the oil-rich MENA region. It was also the case in the wake of the 2001 economic crisis, when reduced business opportunities in Turkey forced qualified companies out of the domestic market and turned their attention to potential business opportunities abroad.[8]

The construction industry was among the worst hit by a severe economic downturn sparked by the Turkish currency crisis in 2018,[9] which sent construction costs soaring, causing builders to postpone some projects and slow the pace of others. Turkey’s economy was just beginning to recover before the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic dragged it back into troubled waters, undermining the construction sector’s recovery at home and abroad.[10]

Turkish companies have also had to contend with unforeseen challenges in markets where they had established a foothold. The Russian financial meltdown in 1998 led to the suspension of Turkish construction projects. The flattening of oil prices and the calamitous 1990-1991 Gulf War took their toll on Turkish companies working in the Gulf, some of which were forced into bankruptcy. Turkish construction activities in Russia slumped again in late 2016, due to political tensions between Moscow and Ankara. Around the same time, Turkish companies that had gained prominence in the Iraqi market were sidelined owing to strained relations between the pro-Sunni Erdoğan and Shiite-led al-Maliki administrations.[11]

Yet, Turkish companies’ opportunism, risk-taking, and resilience has nonetheless paid off. Feeding off the regional construction boom in the Middle East in the 1970s, they concentrated their activities in five oil-producing countries: Libya, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Kuwait, and Iran. When the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) came to an end, Turkish contractors increased their volume of work in Iraq.[12] Despite the collapse of the Russian economy in 1998, they remained at the forefront of the construction market, taking a leading role in many landmark projects.[13] In fact, Turkish companies have repeatedly rebounded from adverse market conditions. The most recent example was last year when, recovering from the pandemic-induced slump, the Turkish construction sector nearly doubled the volume of its overseas projects.[14] The construction industry’s international project portfolio size has kept on growing, and the Turkish labor force employed in overseas projects has risen from 35,000 to 100,000.[15]

Turkish contractors’ ability to survive during recessions and achieve steady growth despite market downturns is not simply a matter of good fortune but is attributable to their flexible strategies, comparative advantages, and growing capabilities. Turkish contractors entered the international market as low-cost bidders to win tenders. By the late 1980s, however, they had begun to capitalize on the rapid assimilation of experience derived from their partnerships with international firms and emerged as a significant force in the Middle East and North Africa.[16]

Initially having served as sub-contractors, they gradually moved into management consultancy, turnkey project implementation, and joint venture investment;[17] and graduated from labor intensive and small-scale, to technology-oriented and large-scale projects.[18] They diversified into global businesses such as banking, tourism, construction materials, and cement production. And they seized opportunities to penetrate new markets, notably Russia and Central Asia following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

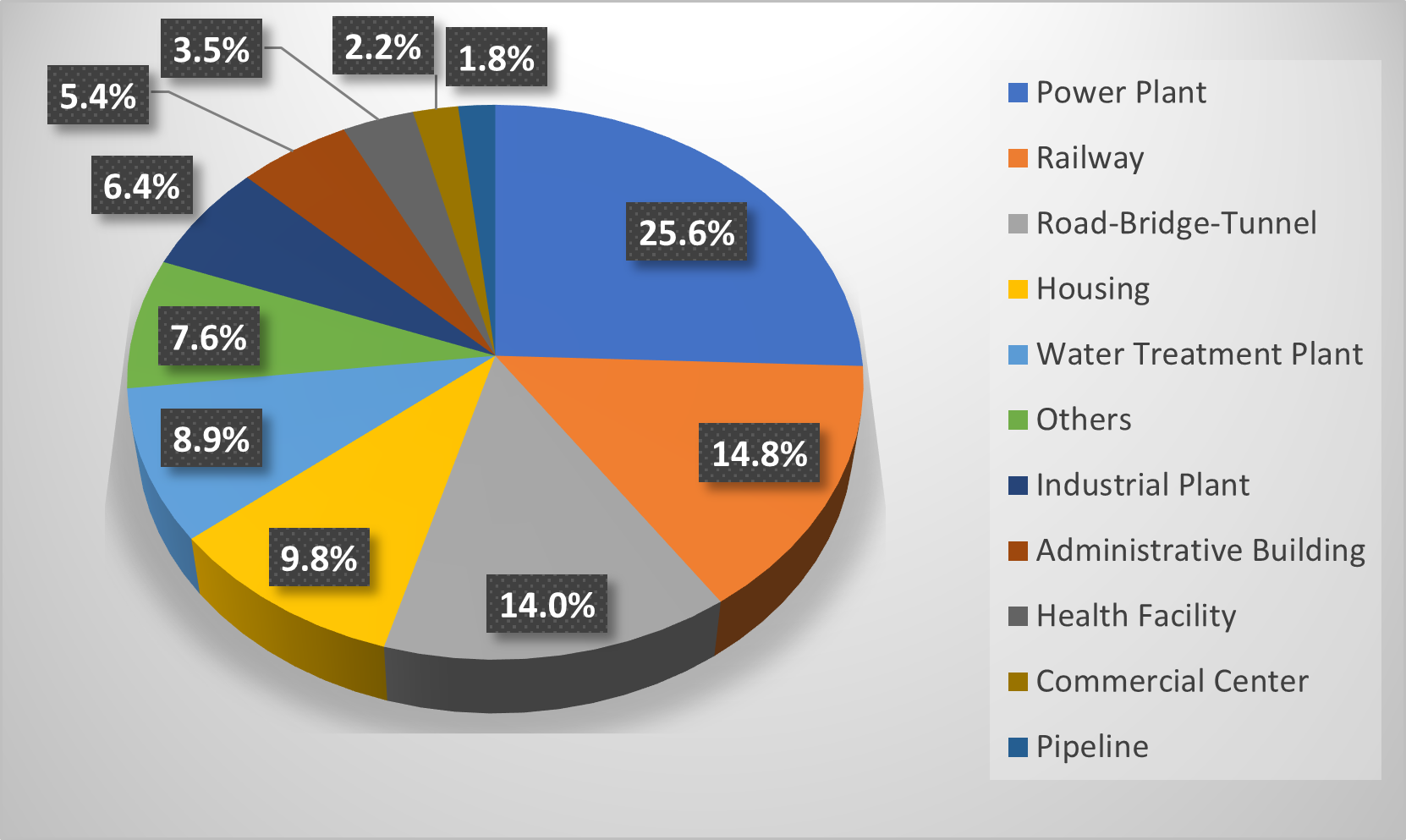

In addition to diversifying their overseas markets, Turkish contractors have differentiated the type of work they perform. [See Chart 1.] Over time, the proportion of projects they have undertaken in the housing sector, which had dominated and still constitutes a large slice of their overseas activities, has shrunk while the share of projects requiring high expertise, project management skills, and advanced technology (e.g., petrochemical facilities) has risen. Several companies have come to specialize in project types such as international airports, railways, and urban metro systems.[19]

Chart 2. International Activities by Type of Work (2021)

Source: Ministry of Trade of Turkey

The pattern of Turkish overseas contracting firms’ portfolios, too, has changed significantly. Some of the larger Turkish companies have taken on the role of investors, rather than only acting as contractors. Moreover, they are presenting more comprehensive project packages than in the past: carrying out market research and feasibility studies; preparing the financial package for the owner; and designing, constructing, and offering maintenance and repair services for the facility.

The defining role of the state

Geographical proximity and cultural affinities shaped Turkish companies’ strategic choices, facilitated their entry, and contributed to their successful penetration of Middle Eastern and Eurasian markets. Equally important has been the role of the state. To be sure, government intervention in the construction industry is not novel, nor in the case of Turkey, is it new. But in the AKP era, the state has become more directly and extensively involved in the sector.[20] In fact, the state has played a defining role in the development and internationalization of the Turkish contracting sector, especially over the past two decades — the period when nearly 90% of Turkey’s projects abroad have been undertaken.[21]

When the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AK Party) swept into office in 2002, the country’s economy was in a dire state. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, then as prime minister and later as president, has championed construction as the engine of domestic economic growth and promoted overseas construction activities as a means of projecting Turkey’s image, power, and influence abroad.[22]

Government patronage has been a crucial factor in aiding the internationalization of Turkish construction service corporations.[23] Construction firms, especially those aligned closely with the AK Party, have been among the main beneficiaries of easy access to credit in the international market, tax incentives and exemptions, and relaxed public procurement practices.[24] Erdoğan has personally presided over the building and functioning of this patronage system, actively directing investment in the housing, energy, and infrastructure sectors across Turkey. The key role that the state has played — with Erdoğan at the helm — in favoring the construction sector by rewarding companies at home has been complemented by efforts to promote overseas construction within the context of Turkey’s assertive and expansive foreign policy.

The diplomatic and business push into Africa

In keeping with his vision of making Turkey a major player on the global stage, Erdoğan has presided over a multidimensional strategy for the African continent. Developed within the framework of the “Opening to Africa Policy” adopted in 1998, the strategy is aimed at bridging the culturally and geographically “near” Maghreb and the “distant” Sub-Saharan Africa.[25]

Spearheading Ankara’s diplomatic and business drive on the African continent, President Erdoğan, who referred to Turkey as “an Afro-Eurasian state,” has personally employed and authorized the use of a variety of soft power tools.[26] Soon after Erdoğan declared 2005 the Year of Africa — incidentally, a year before China did the same —Turkey was admitted as an observer member to the African Union (AU). Three years later, the AU designated Turkey a “Strategic Partner.”

During his time in power, Erdoğan has paid 58 visits to 32 African countries.[27] Turkish Airlines now flies to more destinations (61) in Africa than any other airline. The number of Turkish embassies in Africa has grown from just 12 in 2002 to 43. The Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA) has set up 22 local offices, and the Maarif Foundation operates 175 schools in 26 countries.[28] In a bid to engage and further improve relations with African states, Turkey has built mosques and provided overseas development aid (ODA) as well as humanitarian assistance. Commercial counselors have been deployed across the continent to facilitate the Turkish business community’s smooth entry into African markets. Turkey has also forged security ties with African partners: establishing bases in Somalia and Libya; training and equipping troops in the Sahel; participating in multilateral peacekeeping operations; and selling arms.[29]

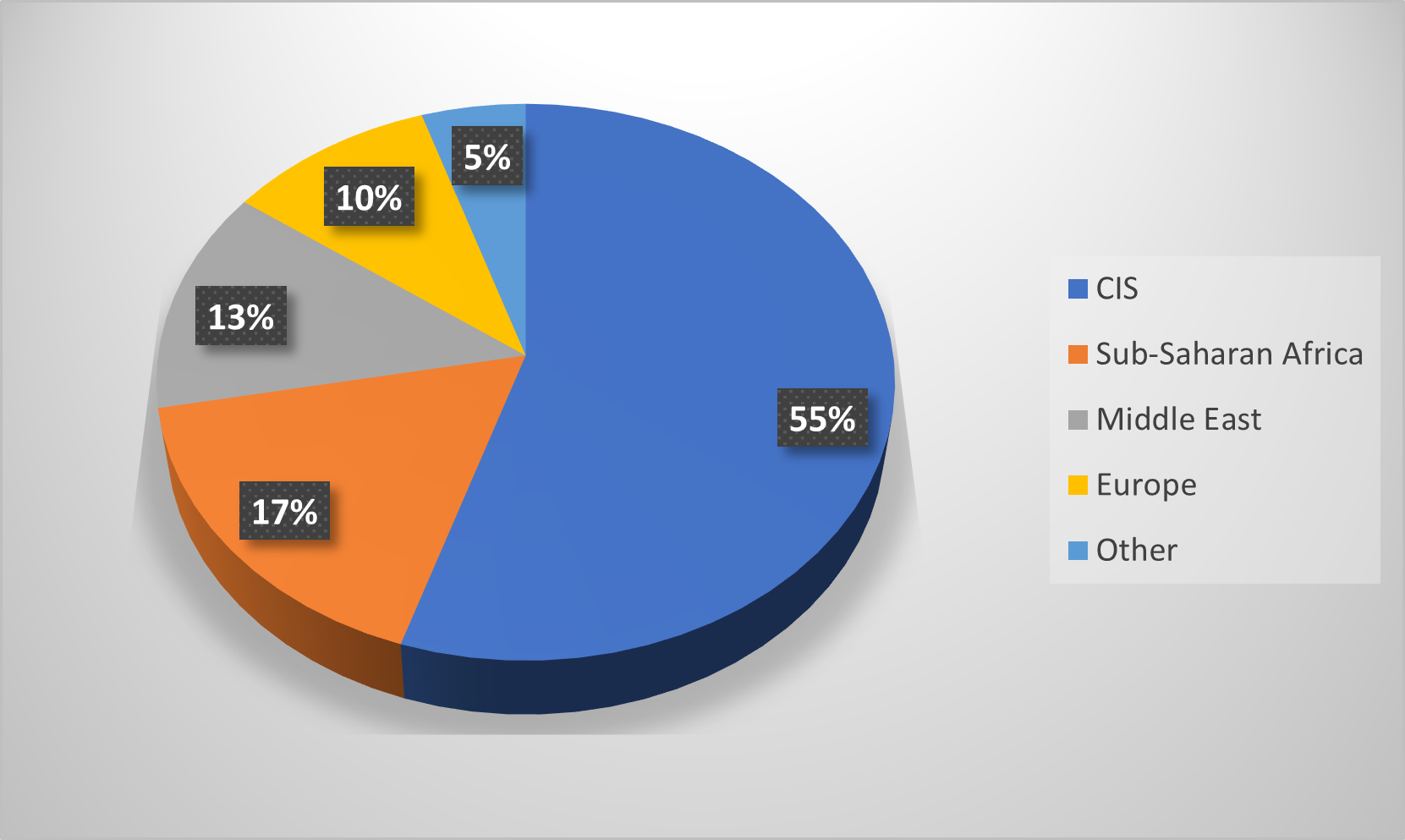

Turkey’s construction companies are agents as well as beneficiaries of this multifaceted engagement. They represent the strongest Turkish business presence in Africa.[30] Most Turkish construction activities have been in the Maghreb, with projects in Algeria and Libya comprising two-thirds of total African projects.[31] But that picture is changing. Turkish companies have become increasingly active in Sub-Saharan Africa.[32] They have fanned out across the continent, undertaking projects in Algeria, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Equatorial Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Libya, Niger, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, and Tunisia.[33] In the regional distribution of business volume, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 17% of Turkish contractors’ projects, surpassing their traditional market.[34] [See Chart 2]

Chart 2. Regional Distribution of Construction Business Volume (2021)

Source: Ministry of Trade of Turkey

Yapı Merkezi, which has implemented 62 railway projects on three continents, has completed or has projects ongoing in Algeria, Ethiopia, Morocco, Senegal, Sudan, and Tanzania.[35] Summa İnşaat built the Dakar Arena, Dakar International Conference Center, the Blaise Diagne International Airport (jointly with Limak), and the airport in Diamey, Niger’s capital. The Albayrak Group built and runs operations at Mogadishu port in Somalia, where it has also constructed roads, a hospital, and the Turkish Embassy. The handiwork of Turkish companies is visible across the continent, in the form of residential and business complexes, hotels, convention centers, sports stadiums, shopping malls, hospitals, and transportation infrastructure.[36] And since the late 2000s, a new wave of smaller-sized entrepreneurs has joined major Turkish firms in targeting Sub-Saharan African markets.[37]

Turkey’s “Third Way”

The successful penetration of African markets by Turkish construction companies, while a mostly private-led enterprise, is embedded in a broader effort initiated, shaped, and shepherded by the state during the AKP era, with President Erdoğan as its chief architect. Although Turkish construction projects in Africa are discrete business activities, they are nonetheless intertwined with and complement other strands of Ankara’s comprehensive engagement strategy.[38] The deployment of that strategy has not occurred in a vacuum. On the contrary, it has taken place in the context of intensifying rivalries involving established and emerging extra-regional powers. Turkey’s efforts to pursue markets, project power, and elevate the country’s status and prestige on the African continent reflect these competitive dynamics — and the activities of Turkish construction companies in Africa are inseparable from them.

In making its diplomatic and corporate push into Africa, Turkey is operating in a crowded field that, besides the Western powers and Russia, includes China, Japan, and India, not to mention the Arab Gulf states. Given this scramble for a presence and influence on the continent, it is not surprising that Turkey has sought to position itself as an emerging global power committed to and capable of challenging established patterns of engagement there. Nor is it surprising that, in doing so, Turkey has presented itself as a viable alternative to both the Western and Chinese models.

Turkey’s “third way” combines business with development and peace-building; displays a preference to deliver aid through bilateral rather than multilateral channels; rejects political conditionality; and emphasizes national ownership.[39] It is cloaked in a narrative that depicts the Ottoman period favorably as a “consent-based” arrangement[40] and portrays Turkey as a “rising but virtuous power” and a “natural partner.”[41] It is a narrative that, with its emphasis on “shared prosperity,” a “partnership of equals,” and “win-win,”[42] deploys language mirroring that of China — Turkey’s biggest competitor in African construction markets.

Neither Turkish nor Chinese officials appear eager to acknowledge publicly their intense head-to-head competition for business in the African construction sector. It is a competition to which China, with much deeper pockets and having gotten an earlier start, has committed far greater resources than has Turkey, especially since the launching of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. Yet, there have been cases where Turkish companies have underbid Chinese rivals.[43] Moreover, in settings where they have operated, Turkish firms for the most part have been well received, gained greater visibility, and enhanced their reputation[44] — thereby arguably improving their competitiveness.

Still, there is no denying the massive financial capabilities that the Chinese state has brought to bear and remains capable of deploying in support of SOEs in African construction markets. It is precisely this element — financing — that has been the major factor disadvantage for Turkish companies. As improbable as it is that they can close the financing gap, Turkish construction firms have taken steps to narrow it: opting for build-operate-transfer (BOT) and project funding models (for which Chinese companies recently are showing less appetite); entering joint venture partnerships with foreign companies that have access to private resources; and securing funds from financial institutions such as the African Development Bank (AfB) and the World Bank.[45]

The Türk Eximbank, despite its own limited financial capacity, has collaborated with institutions such as the Islamic Corporation for the Insurance of Investment and Export Credit (ICIEC) and Japan’s Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI) to provide valuable support to Turkish companies in managing their exposure, overcoming risk concentration, and obtaining cover against project non-payment.[46] Furthermore, where they have competed and won projects against China, such as in Rwanda, Tanzania and Senegal, Turkish contractors have utilized funds from international institutions.

The emergence of Turkey-Japan cooperation in third-country construction services is a potentially significant development in this respect.[47] The Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), together with the Türk Eximbank, have been exploring ways to enhance cooperation between Japanese and Turkish companies in infrastructure construction in Africa.[48] Apart from the potential tangible benefits that such cooperation between Turkey and Japan might yield for their companies and African partners is the interesting question of whether such efforts are indicative of a shared interest in countering China and not simply in expanding their own business activities in Africa.[49]

There are other intriguing possibilities for third-country collaboration as well. Progress in Turkey’s rapprochement with some of its Gulf Arab neighbors as part of the broader regional realignment underway could serve as a catalyst not only for a revival of Turkey’s construction business in the Middle East and the attraction of Gulf funds to domestic projects but also for a shift from proxy political-military conflicts to third-country cooperation in the Horn of Africa and elsewhere on the continent.

There is also scope for third-country collaboration between Turkey and the European Union (EU). Combining Turkey’s high-quality and cost-effective skills in the construction sector with the EU’s technical and financial capacity could pave the way for undertaking climate-resilient public infrastructure projects in North Africa.[50]

Conclusion

Under the AK Party and spearheaded by President Erdoğan, Turkey has sought to present its form of engagement in Africa as a viable alternative to the creation of new relations of dependence with Africa associated with Western or Chinese models of development. Turkey’s construction companies have figured prominently as agents and beneficiaries of Turkey’s ambitious, multidimensional Africa strategy.

Chinese state-owned and private enterprises dominate the financing and development of infrastructure and capital projects in Africa. However, Turkish contractors, as part of their expanding overseas activities, have succeeded in capturing a sizable share and increasing business volume in African construction markets.

The Turkish economy has lately encountered stiff economic headwinds. While growth topped 11% last year, annual inflation skyrocketed to 73.5% in May.[51] The war in Ukraine has increased challenges for the Turkish economy, sending the costs of food, energy, and construction materials soaring. But it is worth mentioning that Turkish contractors have weathered previous periods of economic turbulence, performing well in overseas markets even as they grappled with domestic challenges, and recovering from slack demand or other adversities in their markets of operation.

Turkey’s construction giants are poised to remain a significant force in Africa. By pursuing collaborative third-country construction projects with multiple extra-regional partners, Turkey is unlikely to supplant China as Africa’s master builder. However, this approach could help narrow Turkish contractors’ financing gap, thereby improving their growth prospects. It could also expand the range of choices for African partners in developing the sustainable and resilient infrastructure they desperately need — and in so doing, fulfill Ankara’s promise of a “third way.”

[1] “The new scramble for Africa,” The Economist, March 7, 2019.

[2] Hürcan Aslı Aksoy, Salim Çevik, and Nebahat Tanrıverdi Yaşar, “Visualizing Turkey’s Activism in Africa,” Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS), May 30, 2022, https://www.cats-network.eu/topics/visualizing-turkeys-activism-in-africa.

[3] Kang-Chun Chen, “China is delivering over 30% of Africa’s big construction projects. Here’s why.” The Africa Report, March 22, 2022, https://www.theafricareport.com/183370/china-is-delivering-over-30-of-africas-big-construction-projects-heres-why/; Charles Kenney, “Why Is China Building So Much in Africa?” Center for Global Development, February 24, 2022, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/why-china-building-so-much-africa; Frangton Chiyemura, “Chinese firms — and African labor — are building Africa’s infrastructure,” The Washington Post, April 2, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/04/02/chinese-firms-african-labor-are-building-africas-infrastructure/.

[4] Amir Tavakoli and Sevket Can Tulumen, “Construction industry in Turkey,” Construction Management and Economics 8, 1 (1990): 77-87; Heyecan Giritli et al., “International contracting: a Turkish perspective,” Construction management and economics 8, 4 (1990): 415-430.

[5] Turkish Contractors Association (Türkiye Müteahhitler Birliği, TMB), Turkish International Contracting Services (1972-2021), https://www.tmb.org.tr/files/doc/1623914018902-ydmh-en.pdf; and “Turkish contractors granted contracts worth $3.8 bln abroad in 4 months,” Hürriyet Daily News, May 10, 2022, https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-contractors-granted-contracts-worth-3-8-bln-abroad-in-4-months-173647.

[6] The Turkish contractors in the top 250 list: Rönesans, Limak, Ant Yapı, Yapı Merkezi, Enka, Tekfen, Onur, TAV, Nurol, Esta, Gülermak, Aslan, Sembol, Kuzu, Kolin, Yüksel, Eser, IC İçtaş, Çalık, İlk, GAP, Polat Yol, Alarko, Dekinsan, Gürbaş, Tepe, Makyol, Metag, Üstay, Yenigün, Summa İnşaat, Gama, NATA, Cengiz, MBD, Feka, IRIS, SMK, STFA, and Doğuş. See “40 Turkish firms among top 250 global contractors,” Hürriyet Daily News, August 21, 2021, https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/40-turkish-firms-among-top-250-global-contractors-167350.

[7] M. Talat Birgönül and İrem (Dikmen) Özdoğan, “Competitiveness of Turkish Contractors in International Markets,” in A. Akintoye (ed.), 16th Annual ARCOM Conference, September 6-8, 2000, Glasgow Caledonian University. Association of Researchers in Construction Management, Vol. 1: 95-104.

[8] Heyecan Giritli et al., “International Contracting: A Turkish Perspective,” Construction management and economics 8, 4 (1990): 415-430; Ilknur Akiner and M. Ernur Akiner, “Evaluation of Turkish Construction Industry through the Challenges and Globalization,” Organization, Technology & Management in Construction 1, 2 (2009): 12.

[9] Dorian Jones, “Turkey’s Construction Sector in Crisis,” VOA News, November 28, 2018, https://www.voanews.com/a/turkey-s-construction-sector-in-crisis/4677992.html ; Georgi Kantchev, “Building Boom Unravels, Deepening Turkey’s Economic Crisis,” The Wall Street Journal, September 11, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/dreams-turn-sour-as-turkeys-building-boom-sags-1536658200.

[10] Mahmut Tekçe, “Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic on Turkish Construction Sector,” Korea Institute for International Economic Policy (KIEP), Part 2, No. 6 (2021), https://www.kiep.go.kr/galleryExtraDownload.es?bid=0026&list_no=9312&seq=6.

[11] Zulfikar Dogan, “Foreign policy mishaps prove costly for Turkish contractors,” Al-Monitor, September 26, 2016, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2016/09/turkey-contractors-pay-for-foreign-policy-mistakes.html#ixzz7UiLZE02o.

[12] Beliz Özorhon and Sevilay Demirkesen, “International Competitiveness of the Turkish Contractors.” Paper presented at the 11th International Congress on Advances in Civil Engineering. Istanbul, Turkey. October 21-25, 2014, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267332838_International_Competitiveness_of_the_Turkish_Contractors.

[13] Gilles Valentin, Yaz Yazicioglu, and Emmanuelle Berthemet, “Spreading the word: the Turkish construction sector makes a name abroad,” Arabian Business, June 1, 2007, https://www.arabianbusiness.com/industries/construction/spreading-word-turkish-construction-sector-makes-name-abroad-144219.

[14] “Turkish builders’ projects abroad worth $29.3B in 2021,” Daily Sabah, January 4, 2022, https://www.dailysabah.com/business/economy/turkish-builders-projects-abroad-worth-293b-in-2021; and Deniz Çiçek Palabıyık and Erhan Cihan Ünal, “Turkish construction firms’ overseas projects total $29.3B in 2021: Official,” Anadolu Agency (AA), April 1, 2022, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/turkish-construction-firms-overseas-projects-total-293b-in-2021-official/2465163.

[15] “Turkish contractors take up $30bn projects in 67 countries,” Azernews, January 12, 2022, https://www.azernews.az/region/188113.html.

[16] Guzin Aydogan, “Internationalization of Turkish Contractors: A review of five years.” Paper presented at the 4th Eurasian Conference on Civil and Environmental Engineering (ECOCEE). Istanbul, Turkey. June 17-18, 2019.

[17] Erdener Kaynak and Tevfik Dalgic, “Internationalization of Turkish construction companies: a lesson for third world countries?” Columbia Journal of World Business 26, 4 (1992); M. Talat Birgönül, Irem Dikmen, and Beliz Özorhon, “The impact of reverse knowledge transfer on competitiveness: The Case of Turkish Contractors in Economics for the Modern Built Environment,” in Les Ruddock (ed.), Economics for the Modern Built Environment (London: Routledge, 2008): 212-228; and Marvin Howe, “Turkish Contractors Thrive on Foreign Building Projects,” The New York Times, March 20, 1982, https://www.nytimes.com/1982/03/20/business/turkish-contractors-thrive-on-foreign-building-projects.html.

[18] Aytaç Gökmen and Dilek Temiz, “Construction Business as a means to Internationalize and Develop: A Critical Analysis of the Turkish Construction Sector and Reflections on the Economy,” Journal of Business, Economics & Political Science 1, 2 (2012): 31-51.

[19] Ilknur Akiner and Ibrahim Yitmen, “International Strategic Alliances in Construction: Performances of Turkish Contracting Firms.” Management and Innovation for a Sustainable Built Environment, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. June 20-23, 2011, https://www.academia.edu/9686631/INTERNATIONAL_STRATEGIC_ALLIANCES_IN_CONSTRUCTION_PERFORMANCES_OF_TURKISH_CONTRACTING_FIRMS.

[20] Ismail Doga Karatepe, Chapter 2, “Turkey as an Intriguing Case: Placing Turkey in an International Context, in The Cultural Political Economy of the Construction Industry in Turkey (Brill, 2020): 17-32.

[21] “Turkish contractors granted contracts worth $3.8 bln abroad in 4 months,” Hürriyet Daily News, May 10, 2022, https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-contractors-granted-contracts-worth-3-8-bln-abroad-in-4-months-173647.

[22] It is important to note here that the construction-based, finance-led growth regime helped usher in a long period of economic expansion. However, over-reliance on the construction sector loans denominated in foreign currency, heavy dependence on imported construction materials, and sensitivity to global downturns. Some megaprojects costly and controversial, propelled by easy foreign credit, questionable tendering procedures, lack of public scrutiny, adverse environmental impacts, collateral damage to the country’s cultural heritage, and neglect of the manufacturing sector. See: Andrew Wilks, “For Erdogan’s Istanbul Canal project, critics see few winners,” Aljazeera, April 16, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/4/16/for-erodgans-istanbul-canal-project-critics-see-few-winners; Jonathan Gorvett, “Erdogan Is Digging a Hole He Can’t Escape,” Foreign Policy, April 28, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/04/28/canal-kanal-istanbul-erdogan-channel-trench-protest/; Piotr Zalewski, “Turkey’s construction boom appears to be over,” Financial Times, November 27, 2014, https://www.ft.com/content/910a4a32-5093-11e4-8645-00144feab7de; Carlotta Gall, “A Canal Through Turkey? Presidential Vote Is a Test of Erdogan’s Building Spree,” The New York Times, June 21, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/21/world/europe/turkey-election-ergodan-canal-megaprojects.html; Alexander Sekhniashvili, “Authoritarian Infrastructure Complex: The Turkish Tale,” CSIS New Perspectives in Foreign Policy, Issue 14 (December 20, 2017): 34-38, https://www.csis.org/npfp/authoritarian-infrastructure-complex-turkish-tale; Levent Kenez, “Turkey sets conditions in international agreements in favor of businessmen close to Erdoğan,” Nordic Monitor, July 6, 2021, https://nordicmonitor.com/2021/07/turkey-sets-conditions-to-international-agreements-in-favor-of-businessmen-close-to-erdogan/; Dryad Global, “Erdogan’s Sinister Game in Libya: Construction Corruption,” The Investigative Journal, January 28, 2021, https://channel16.dryadglobal.com/erdogans-sinister-game-in-libya-construction-corruption.

[23] Özlem Öz, “The Competitive Advantage of Turkey,” chapter 2, The Competitive Advantage of Nations: The Case of Turkey (London: Routledge, 1999).

[24] Berk Esen and Sebnem Gumuscu, “Building a Competitive Authoritarian Regime: State–Business Relations in the AKP’s Turkey,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 20, 4 (2018), 349-372, DOI: 10.1080/19448953.2018.1385924; Sultan Tepe and Ayça Alemdaroğlu, “How Authoritarians Win When They Lose,” Journal of Democracy 32, 4 (2021): 87-101; Daron Acemoğlu and Murat Üçer, “High-Quality Versus Low-Quality Growth in Turkey - Causes and Consequences,” CEPR Discussion Papers 14070 (2019), http://www.cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=14070; “Five pro-gov’t construction companies granted tax incentives 128 times in last decade,” duvaR.com, December 24, 2020, https://www.duvarenglish.com/five-turkish-pro-govt-construction-companies-granted-tax-incentives-128-times-in-last-decade-news-55618.

[25] Mehmet Özkan and Birol Akgün, “Turkey’s Opening to Africa,” The Journal of Modern African Studies 48, 4 (2010): 525-546. doi:10.1017/S0022278X10000595; Federico Donelli, “Turkey’s involvement in Sub-Saharan Africa: an empirical analysis of multitrack approach,” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 40, 1 (2022): 18-33. DOI: 10.1080/02589001.2021.1900551; Mehmet Özkan, “A New Actor or Passer-By? The Political Economy of Turkey’s Engagement with Africa,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 14, 1 (2012): 113-133, https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2012.656968; Abdinor Dahir, “The Turkey-Africa Bromance: Key Drivers, Agency, and Prospects,” Insight Turkey 23, 4 (2021): 27-38, https://www.insightturkey.com/file/1414/the-turkey-africa-bromance-key-drivers-agency-and-prospects; Chigoze Enwere and Mesut Yilmaz, “Turkey’s Strategic Relations with Africa: Trends and Challenges,” Journal of Economics and Political Economy 1, 2 (2014): 216-230.

[26] Aysa Akca, “Neo-Ottomanism: Turkey’s Foreign Policy Approach to Africa,” CSIS New Perspectives in Foreign Policy 17 (April 8, 2019), https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/190409_NewPerspectives_Akca.pdf.

[27] Ibrahim Kalin, “Turkey’s win-win policy in Africa,” Daily Sabah, January 28, 2017, https://www.dailysabah.com/columns/ibrahim-kalin/2017/01/28/turkeys-win-win-policy-in-africa.

[28] Burhanettan Duran, “From initiative to partnership: Turkey-Africa ties,” Daily Sabah, December 20, 2021, https://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/columns/from-initiative-to-partnership-turkey-africa-ties.

[29] Brandon J. Cannon, “Turkey’s Defense Industry and Military Sales in Sub-Saharan Africa: Trends, Rationale, and Results,” TRENDS Research and Advisory, December 20, 2021, https://trendsresearch.org/insight/turkeys-defense-industry-and-military-sales-in-sub-saharan-africa-trends-rationale-and-results/; Elif Selin Calik, “Turkey’s drones diplomacy in Africa,” Al-Monitor, January 7, 2022, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20220107-turkeys-drones-diplomacy-in-africa/; Ash Rossiter and Brendan J. Cannon, “Re-Examining the ‘Base’: The Political and Security Dimensions of Turkey’s Military Presence in Somalia,” Insight Turkey 21, 1 (2019): 167-188, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26776053.

[30] Charlie Mitchell, “Erdogan’s ambition drives Turkey’s Africa surge,” African Business, March 17, 2021, https://african.business/2021/03/trade-investment/erdogans-ambition-drives-turkeys-africa-surge/.

[31] Michaël Tanchum, “Turkey’s Maghreb–West Africa Economic Architecture: Challenges and Opportunities for the European Union,” SWP Working Paper No. 3, June 2021, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/arbeitspapiere/CATS_Working_Paper_Nr_3_Michael_Tanchum_Turkeys_Maghreb_West_Africa_Economic_Architecture.pdf.

[32] “Turkish contractors assume projects worth $20 billion this year,” Hürriyet Daily News, November 3, 2021, https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-contractors-assume-projects-worth-20-billion-this-year-169079.

[33] “Turkish builders are thriving in Africa,” The Economist, May 7, 2022; and “Logements sociaux dorés sur tranche pour les turcs Atlas, Ozgur et Doruk,” Africa Intelligence, January 27, 2021, https://www.africaintelligence.fr/afrique-du-nord_business/2021/01/27/logements-sociaux-dores-sur-tranche-pour-les-turcs-atlas-ozgur-et-doruk,109637717-art.

[34] Palabıyık and Ünal, “Turkish construction firms’ overseas projects total $29.3B in 2021: Official”; and Turkish Contractors Association (Türkiye Müteahhitler Birliği, TMB), Turkish International Contracting Services (1972-2021), https://www.tmb.org.tr/files/doc/1623914018902-ydmh-en.pdf.

[35] Andrea Ayemoba, “Turkish builder signs $1.9b railway construction deal with Tanzania,” Africa Business Communities, December 29, 2021, https://africabusinesscommunities.com/news/turkish-builder-signs-$1.9b-railway-construction-deal-with-tanzania/.

[36] N.J. Ayuk, “Turkish construction companies help to move Africa forward,” African Business, March 15, 2020, https://african.business/2020/03/economy/turkish-construction-companies-help-to-move-africa-forward/.

[37] Aain Vicky, “Turkey Moves into Africa,” Le Monde Diplomatique, May 2011, https://mondediplo.com/2011/05/08turkey.

[38] David Shinn, “Turkey’s Engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa Shifting Alliances and Strategic Diversification,” Chatham House (September 2015): 4, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/field/field_document/20150909TurkeySubSaharanAfricaShinn.pdf.

[39] Alican Tekingunduz, “From building schools to wells: Ordinary Turks lend a hand in Africa,” TRTWorld, November 20, 2020, https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/from-building-schools-to-wells-ordinary-turks-lend-a-hand-in-africa-41620.

[40] Lerna K. Yanık, “Constructing Turkish ‘exceptionalism’: Discourses of Liminality and Hybridity in post-Cold War Turkish Foreign Policy,” Political Geography 30, 2 (2011): 80-89.

[41] Mark Langan, “Virtuous Power Turkey in sub-Saharan Africa: The “Neo-Ottoman” Challenge to the European Union,” Third World Quarterly 38, 6 (2017): 1400; and Julia Harte, “Turkey Shocks Africa,” World Policy Journal 29, 4 (2012): 27-38.

[42] Ibrahim Kalin, “Turkey’s win-win policy in Africa,” Daily Sabah, January 28, 2017, https://www.dailysabah.com/columns/ibrahim-kalin/2017/01/28/turkeys-win-win-policy-in-africa.

[43] Yunnan Chen, “Laying the Tracks: The political economy of railway development in Ethiopia’s railway sector and implications for technology transfer,” Boston University Global Development Policy Center, GCI Working Paper 14 (January 2021), https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2021/01/GCI_WP_014_Yunnan_Chen.pdf; “Tanzania courts Turkey for its rail megaproject, casting doubt on China’s role,” Global Construction Review, January 24, 2017, https://www.globalconstructionreview.com/tanzania-courts-turkey-its-rail-megaproject-castin/; and “Turkish firm wins contract to finish building Kigali centre,” The East African, April 25, 2015, https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/turkish-firm-wins-contract-to-finish-building-kigali-centre--1335240.

[44] These actors include: Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA), The Foreign Economic Relations Board of Turkey (DEIK), Maarif Foundation Schools, Yunus Emre Institute, Red Crescent, Anadolu Agency, and Diyanet Foundation. See Chen, “Laying the Tracks: The political economy of railway development in Ethiopia’s railway sector and implications for technology transfer”; “Turkish Construction Companies Help to Move Africa Forward, Real Estate Monitor Worldwide, March 16, 2020; Sinan Tavsan, “Turkey’s push into Africa has China looking over its shoulder,” Nikkei Asia, September 15, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Indo-Pacific/Turkey-s-push-into-Africa-has-China-looking-over-its-shoulder; Özlem Öz, “Sources of competitive advantage of Turkish construction companies in international markets,” Construction Management and Economics 19, 2 (2001): 135-144. DOI: 10.1080/01446190010009988; and Altay Atli, “Businessmen as Diplomats: The Role of Business Associations in Turkey’s Foreign Economic Policy,” Insight Turkey 13, 1 (2011): 108-128.

[45] Andrea Ayemoba, “Turkish builder signs $1.9b railway construction deal with Tanzania,” Africa Business Communities, December 29, 2021, https://africabusinesscommunities.com/news/turkish-builder-signs-$1.9b-railway-construction-deal-with-tanzania/; and Mehmet Özkan and Birol Akgün, “Turkey’s opening to Africa,” The Journal of Modern African Studies 48, 4 (2010): 525-546. DOI:10.1017/S0022278X10000595.

[46] For details regarding the ICIEC, which is a member of the Islamic Development Bank Group, see: https://iciec.isdb.org/. See also: Islamic Development Bank Group, “THE POWER OF PARTNERSHIPS: The ICIEC-Turkey Story,” December 2020, https://iciec.isdb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Turkey-Strategic-Business-Partnership-Eng-2019.pdf; Berne Union, “Türk Eximbank’s Experience in Sub-Saharan Africa,” The Bulletin, June 15, 2021, https://www.berneunion.org/Articles/Details/582/Turk-Eximbanks-Experience-in-Sub-Saharan-Africa; Orhan Yavuz Mavioglu et al., “Construction and Projects in Turkey: Overview,” Thomson Reuters, September 1, 2021, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/w-019-2661?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&firstPage=true; and Andrea Ayemoba, “Turkish builder signs $1.9b railway construction deal with Tanzania,” Africa Business Communities, December 29, 2021, https://africabusinesscommunities.com/news/turkish-builder-signs-$1.9b-railway-construction-deal-with-tanzania/.

[47] “Turkey, Japan deal for construction services in third countries,” Daily Sabah, March 13, 2018, https://www.dailysabah.com/business/2018/03/13/turkey-japan-deal-for-construction-services-in-third-countries-1520895337.

[48] “Turkish, Japanese business circles eye further cooperation in Africa,” Daily Sabah, June 20, 2019, https://www.dailysabah.com/business/2019/06/20/turkish-japanese-business-circles-eye-further-cooperation-in-africa; Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), “JBIC Holds Business Matching Seminar with Türk Eximbank to Promote Cooperation between Japanese and Turkish Companies in Africa,” Press Release, March 18, 2018, https://www.jbic.go.jp/en/information/topics/topics-2019/0731-012388.html.

[49] “Will Turkey steal competitive advantage from China in Africa,” Nikkei Asia, March 16, 2021, in Vestnik Kavkaza, https://en.vestikavkaza.ru/analysis/Will-Turkey-steal-competitive-advantage-from-China-in-Africa.html; Semiha Karaoğlu, “Power Struggle in the Rising Continent of Africa,” Institute for International Strategy and Information Analysis (IISIA), May 13, 2022, https://asiapowerwatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Turkey-role-in-China-Japan-competition-in-Africa-S-Karaoglu.pdf; and Cobus van Staden, “Japan and Turkey Targeting China in Africa,” China Global South Project, May 19, 2022, https://chinaglobalsouth.com/2022/05/19/japan-and-turkey-targeting-china-in-africa/.

[50] Pınar Akpınar et al., “A new formula for collaboration: Turkey, the EU & North Africa,” Sabancı and Clingendael Report (March 2022): 26-31, https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/Report_New_formula_for_collaboration_Turkey_EU_NorthAfrica.pdf.

[51] Ezgi Erkoyun and Nevzat Devranoglu, “Turkey inflation soars to 73%, highest since 1998,” Reuters, June 3, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/turkeys-annual-inflation-soars-24-year-high-73-2022-06-03/.

Photo by Murat Kula/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.