China has become the new polarizing factor in Iranian politics. The latest issue is the 25-year deal between Iran and China, which, according to Abbas Milani of Stanford University, will make Iran a “colony” of China — a treaty even worse than the 1872 Reuter Concession, which gave a British businessman control over Iran’s roads, communications, and natural resources. Opposition to the proposed deal with China comes from politicians across the political spectrum. Former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad described it as “a suspicious, secretive deal” and Reza Pahlavi, the son of Iran’s ousted Shah, slammed it as a shameful treaty that “places foreign soldiers on our soil.” Despite rumours and speculation on social media about Iran’s intention to give control of its southern islands to China, permit China to construct a military base on its soil, and sell oil and gas to China at a discount, there are no provisions in the agreement from which to draw such conclusions.

To begin with, there is no actual deal — at least not yet. There have been ongoing negotiations between Iran and China since 2016 over a strategic cooperation framework. These talks have resulted in an 18-page document titled “Sino-Iranian Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” approved by President Hassan Rouhani’s administration in June 2020. However, the partnership document is drafted in non-binding terms and is more akin to a statement of intent.

What does it entail?

The document covers diverse areas of cooperation including energy, petrochemicals, nuclear capabilities, roads and ports, finance, tourism, science, technology, and military affairs. It comprises a four-page “Program of Comprehensive Cooperation between China and Iran,” outlining the agreement titles and terms of nine articles. Three appendixes complement it: “General Objectives,” “Main Subjects for Program of 25-Year Comprehensive Cooperation,” and “Executive Measures.” The main areas of cooperation between the two countries are listed as oil and energy, Iran’s “active participation” in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), development of the Makran coast, technology and telecommunication, and the financial, military, and political areas. One significant point that will guarantee Iran a sustainable and stable energy market for the coming decades (in the volatile and tightening competitive oil market) is an agreement over China’s investment in Iran’s upstream and downstream oil and gas industries. Regarding infrastructure, developing a South-North corridor (Chabahar-Central Asia), South-West corridor (Chabahar and Bandar Abbas-Turkey and Azerbaijan), and the Pakistan-Iran-Iraq-Syria “pilgrimage railroad,” are among the notable initiatives. Iran’s current sanction-stricken economy and its need for investments in energy and infrastructure explains the enthusiasm of the Iranian leadership to embrace the deal.

The most alarming aspect of the document relates to cooperation in the telecommunication sector, which has significant implications for civil society in Iran. Ironically, this aspect has been overlooked by observers. The document provides for cooperation in developing telecommunication infrastructure (Digital Silk Road, 5G), basic services (search engines, email, and messaging applications), communication equipment (satellite navigation, switches, servers, and data storage), and consumer products (mobile phones, tablets, and laptops). Cooperation extends to developing operating systems for computers and mobile phones, internet search engines, and anti-virus software. It seems the main purpose of this technological cooperation is to provide Iran with the know-how and equipment to enable its full decoupling from the global internet and form the dreaded National Information Network, similar to China’s Great Firewall. This network was fully deployed during the seven-day internet blackout of December 2019 amid bloody protests over the fuel price hike, which claimed more than 300 lives. However, the blackout was not sustainable as it disrupted businesses and the daily operation of the government. But with Chinese search engines, email services, messaging apps, and social media, Iran will be able to block the external internet for a long time without risking everyday online operations.

Feasibility and timing

Another intriguing point about the Sino-Iranian Comprehensive Strategic Partnership is its feasibility. Given Washington’s stringent and comprehensive sanctions on Iran, how is China going to implement these commitments? This is noteworthy given that after Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and re-instating of sanctions, most Chinese companies have reneged on agreements with their Iranian counterparts. For example, China National Petroleum Corp pulled out of the $5 billion deal to invest in Iran’s South Pars field last year due to U.S. pressure. Further, China’s import of Iranian oil had plunged by 88.9 percent in March 2020, compared to a year earlier. Chinese companies have already paid a hefty price for their violations of U.S. sanctions on Iran. In 2017, ZTE, the giant Chinese telecommunication company, was fined $1.19 billion for violating U.S. sanctions on Iran and North Korea. In 2018, Huawei Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou was detained in Canada for violating Iran sanctions. A year later, Washington blacklisted several Chinese companies for shipping Iranian oil. And the list goes on. So, the questions remain: how can the Sino-Iranian Comprehensive Strategic Partnership be realized in practice? What kind of legal, financial, or political miracle is needed to make this sweeping cooperation with Iran possible in light of Washington’s harsh sanctions?

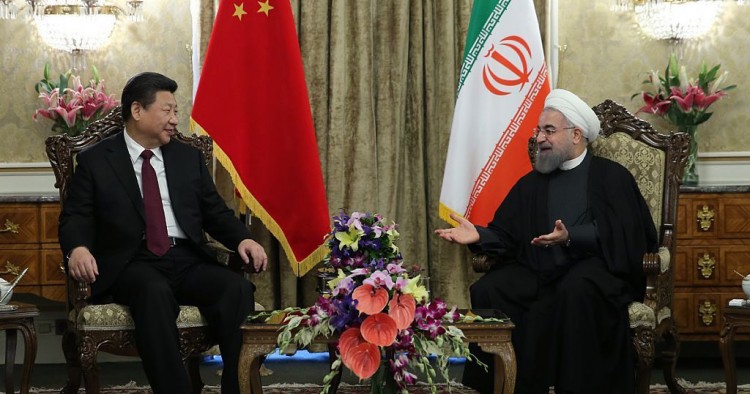

This brings us to another question, about the timing of the project, which prompts speculation about its real intention. While early steps toward this agreement were taken in 2016, during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Tehran, and led to the publication of the “Joint Statement on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” at the time, it was left dormant for almost four years and only resurfaced in June 2020. The revival of the cooperation concept coincides with heightened tensions between Washington and Beijing over a range of issues, including the mismanagement of COVID-19, territorial claims in the South China Sea, the new security law in Hong Kong, and the persecution of Muslims in Xinjiang. Given the past occasions of China using the “Iran card” as leverage against the U.S., one wonders if the re-emergence of the proposed treaty is another instance of China using Iran to challenge the U.S. If that is the case, it certainly would frustrate Trump’s administration, which has tried hard in the last few years to curb Iran’s regional influence through its “maximum pressure” policy. The U.S. reaction so far has been decisively against the China-Iran deal. A U.S. State Department spokeswoman emphasized that “the United States will continue to impose costs on Chinese companies that aid Iran.” Only time can tell if changes in Sino-U.S. relations — for good or bad — will affect the China-Iran partnership agreement.

Professor Shahram Akbarzadeh is the convener of the Middle East Studies Forum at Alfred Deakin Institute, Deakin University, Australia. Mahmoud Pargoo is a researcher at the Middle East Studies Forum at Alfred Deakin Institute, Deakin University, Australia. The views expressed in this piece are their own.

Photo by Pool/Iranian Presidency/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.