Kawkaba: Highlights from the Barjeel Art Foundation, a new exhibition of works by artists from across the Middle East and North Africa that opened recently at Christie’s in London, bears the name of the Arabic word for constellation. Fittingly, it shines a light on the region’s mid-century moment when art was often part of a process of post-colonial nation building. The exhibition is a star-studded journey through the region’s 20th century histories and aesthetics, showcasing lesser-known artists along with the greats. Curated by Ridha Moumni, deputy chairman of Christie’s Middle East and billed as the largest exhibition of Arab art in London to date, it features 110 works culled from the Barjeel Art Foundation’s collection, most of which have never been seen before in the city.

During a tour for the Middle East Institute, the foundation’s founder, businessman, collector, commentator, and scholar Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, explains that while there is currently great “momentum” within the world of Middle Eastern art with interest from collectors and museums in contemporary art from the region, “I always thought it was important to show that these artists have traditions that are rooted in modernity and that in spite of the popular assumption that Middle Eastern art is only a few decades old, it goes back a century or more in terms of modernity.”

Al Qassemi, who owns one of the world’s largest collections of art from the MENA region, says the exhibition is about “moving the needle back a hundred years to show that from the turn of the century until the mid-century, there were many artists creating art with similar traditions and inspirations as today — revivalists who reinvigorated traditional arts and crafts and drew inspiration from heritage.”

Celebration of women artists and the cosmopolitanism of MENA’s mid-century moment

Kawkaba is also about showcasing the work of unsung women artists — who make up 50% of the exhibition — as well as religious and ethnic minorities, with work by artists of Jewish, Christian, Druze, Amazigh (Berber), Armenian, Circassian, and Turkish descent included in the 110 paintings, sculptures, and installations.

“It was important for me to capture the cosmopolitanism of the mid-20th century in the region,” notes Al Qassemi, who founded the non-profit Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates, in 2010 as a way to manage his considerable private collection of artwork from the MENA region. The foundation, whose private collection comprises over 1,000 modern and contemporary works, has mounted two dozen exhibitions since 2013. In May 2018, the collection moved to a long-term exhibit at the Sharjah Art Museum.

“I feel an extra sense of responsibility to showcase the collection to the public,” Al Qassemi explains, citing an important educational aspect. While getting export licenses from countries like Algeria, which have strict protocols protecting their modernist cultural heritage, can take years, he says it’s much easier to negotiate with the families of artists, “who sell to me because they know I will exhibit the work widely.” Beyond its aesthetic value, the exhibition is also a device for connecting with the larger MENA diaspora and the families of the artists. “So far we have had the family members of Ibrahim el-Salahi (Sudan), Mona Saudi (Jordan), Hussein Shariffe (Sudan), Hamed Abdalla (Egypt), Jumana el-Husseini (Palestine), Mohammed Ghani Hikmat (Iraq), and Said Tahsin (Syria) visit the Kawkaba exhibition,” Al Qassemi notes.

Currently Al Qassemi is working with the family of Tahsin to track down a missing triptych of paintings, gifted to Saudi Arabia by Syrian President Fawzi Selu in 1953, depicting the battles of Qadisiyah, Zat Sawari, and Yarmouk. The family hopes to include them in a book of the artist’s memoirs being compiled by his grandson.

Al Qassemi adds to his collection via a network of buyers across the region — friends, gallerists, and scholars. “I’m keen on collecting work by women modern artists,” he notes. “I read a lot and often depend on scholarship to find names of artists who may be mentioned in some books but their works are not always seen.”

The work of under-celebrated women artists is certainly on display in Kawkaba. The mid-century moment in the MENA region was a time of optimism, progress, and nationalism, and also a time when many women artists led the way in abstract and other art forms.

The exhibition deftly captures this historical moment, opening with a “space age” series of works including Egyptian artist Abdel Hadi el-Gazzar’s early 1960s oil on canvas Two People in Space Outfits. Here two slightly androgynous figures in “space suits” — one more male and one more female in appearance — contemplate a brave new decade. The painting is accompanied by two other works of note by women artists: Lebanese painter Samia Osseiran Jumblatt’s 1970 painting Formative Radiation, depicting two planetary orbs that evoke the embryonic union of mother and child, and Egyptian artist Menhat Helmy’s 1973 oil on canvas Space Exploration/Universe celebrating the cosmos as an infinite radial grid of blues and reds. The revelation of these women artists feels like the birth of an unknown star in an often-male-dominated art world universe.

A cross-regional dialogue of women artists on the gallery walls

Indeed, the exhibition also functions as a meeting place for the work of modern women artists from the region who may have not met in person but whose paintings dialogue on the gallery walls.

In one section the work of Safia Farhat, a pioneering artist and activist in post-independence Tunisia, whom Al Qassemi credits with championing arts and crafts at a time when they were “relegated to the periphery,” rubs shoulders with work by Lebanese abstract artist Etel Adnan. Here, the work of Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair, who was the first artist in the MENA region to exhibit abstract work in the 1940s and showed at the Tate Modern in 2013, converses with that of Khadigah Riad, a pioneer of abstract art in Egypt.

“My goal was to expand the list of women artists from the MENA beyond the usual five or six in the public awareness,” says Al Qassemi. And so, alongside a few works by big contemporary names like Mona Hatoum and Zaha Hadid, he has.

On exhibit is the work of Iraqi-born sculptor Moazaz Rawda, a woman of Turkish parentage who started the first kindergarten in Baghdad in 1926. She later married a wealthy Lebanese doctor and went back to art school at age 50. She became the first woman in Lebanon to have a public commission, completing the famous Dubke Monument in Beirut in the 1950s.

A rare treat in a small side gallery is a 1967 oil painting by Algerian artist Djamila Bent Mohamed called Siblings depicting her sisters. Framed by traditional North African motifs, adjacent skeletal figures evoke the ghost of the independence war. As Al Qassemi notes, most online references to Bent Mohammed are not as an artist of significance but as a prisoner of the French, who arrested her for her activism. Part of the private collection of a French citizen, it took him a year to export it from Algeria.

A fusion of aesthetic and political movements intertwined in the 20th century

There are of course many works of note by male artists as well, including Algerian Mohammed Issiakhem’s work from the late 1970s, an oil on canvas depicting a Berber woman as the “mother of the nation” in a piece called Femme et Mur (“Woman and Wall”).

Also included is the work of seminal figures like Kadhim Hayder, one of Iraq’s “pioneer” artists and a founding member of the Baghdad Group of Modern Art, which explored ways to integrate Iraq's ancient art heritage with modern techniques; and Sudanese painter Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq, a foundational figure in the Sudanese modernist movement, known as the Khartoum School, who later established the Crystalist Group, a conceptual art group that challenged traditional practices in Sudanese art and countered the prevailing version of state socialism with more liberal views. The exhibition naturally fuses both the aesthetic and political movements that were so intertwined in the 20th century.

Many artists’ families, says Al Qassemi, “have come to me with stories of works.” The grandson of Said Tahsin, for example, gave important context to the painting in the exhibition of Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser. Created in 1962 at the time when Egypt and Syria merged into the United Arab Republic, his grandson said that the artist was “celebrating Nasser as a unifying leader.”

Meanwhile Iraqi artist Dia al-Azzawi’s haunting 1968 oil on canvas, A Wolf Howls: Memories of a Poet, is based on a poem by renowned Iraqi poet Muzaffar al-Nawab about a fallen comrade killed by Baathists, offering a stark reminder of the darker side of the nationalist project.

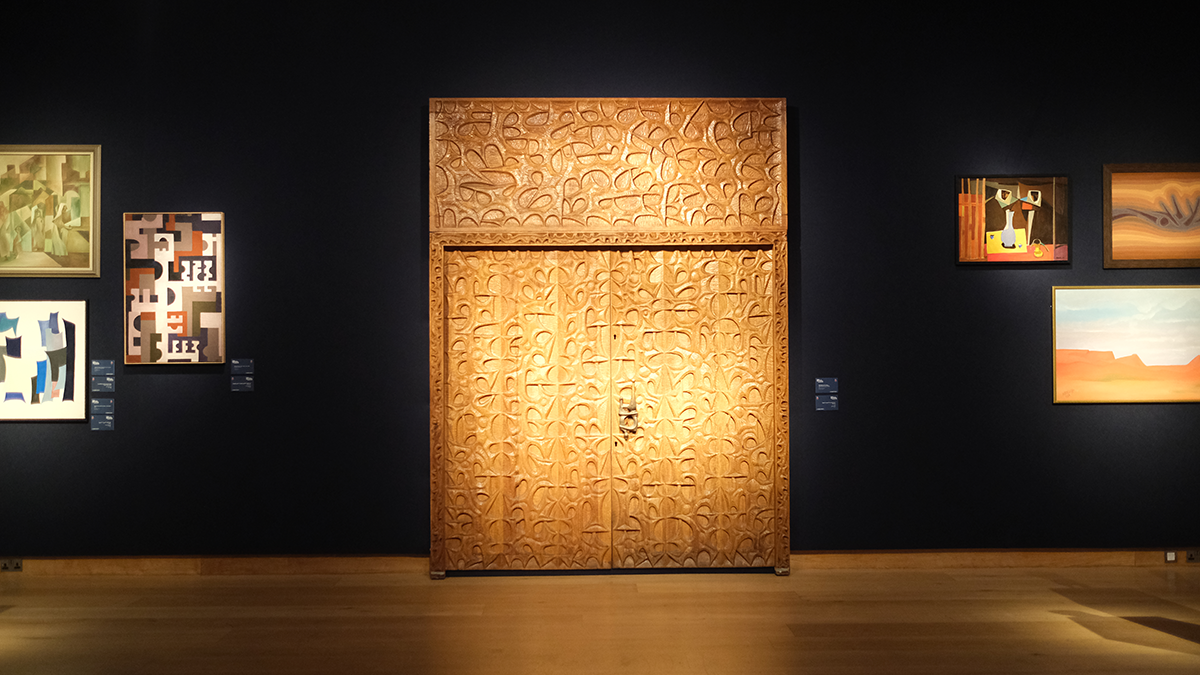

Mohammed Ghani Hikmat’s Bab El Gharbaa, billed in the catalogue as “Gateway to the West” (which one of his relatives who attended the exhibition opening corrected to “Gateway to Exile”), is situated opposite the gallery entrance, in a clever mirroring of portals. The intricately carved door offers an ambiguous evocation of both the strength and beauty of Iraqi heritage and perhaps its dissolution through emigration. The late sculptor, known for his statues of 1001 Nights characters like Scheherazade in Baghdad, fled his beloved city in the wake of the 2003 U.S. invasion, returning later to find that 150 of his works from the National Museum had been looted and his studio and many sculptures damaged.

Sudanese artist Omer Khairy’s vibrant 1975 Khartoum Market Scene offers a poignant and nostalgic look at a nation now in flames, while Egyptian Jewish artist Ezekiel Baroukh’s 1939 Portrait of Mademoiselle A.C. evokes a vanished Alexandria, once a meeting place between East and West. But it is in the juxtaposition of works by male and female contemporaries where Kawkaba finds its greatest strength.

Juxtapositions of works by male and female contemporaries

Consider two adjacent works in the gallery’s Great Room: Syrian artist Leila Nseir’s 1978 oil on canvas The Martyr/The Nation commemorating the killing of a woman aid worker by a militia in Beirut that movingly captures the anguish of the Lebanese civil war. With images evoking the Madonna and child, it challenges the traditional narrative of the male fedayeen (freedom fighter) by simultaneously mourning and celebrating her sacrifice. In contrast, Moscow-trained Iraqi modernist pioneer Mahmoud Sabri’s 1963 The Hero depicts a political martyr, but in a more masculinist style — a kind of Goya in Baghdad married to Russian expressionism.

Iraqi artist Naziha Salim’s untitled 1963 oil on canvas is a welcome addition to the exhibition, as is her older brother Jewad Selim’s 1953 work, Woman Selling Material, hung in the “arts and crafts” section. It’s interesting to see this work above a 1979 three-dimensional ceramic relief by Vera Tamari called Palestinian Women at Work and near Jewish Egyptian artist and surrealist poet Joyce Mansour’s found object sculptures of nails and screws. Selim died before his famous Monument to Freedom, commissioned by Iraqi Prime Minister Abdul Karim Qasim in 1959 to celebrate the 1958 Revolution, was finished. Still he managed to subvert Qasim’s intent to have his image included in the work by making it a paean to the people's strife against tyranny and an ode to Iraq’s rich history, incorporating Abbasid and Babylonian style wall reliefs. The juxtaposition of his 1953 work with craft and heritage focused pieces is a reminder that for Selim, like many of the artists in the exhibition, the concept of homeland was one deeply rooted in culture and indigeneity, rather than the cult of leadership.

Kawkaba is a significant show not only for the under-celebrated artists it showcases alongside the famous, but also for its evocation of a long-lost mid-century moment, when state-funded art was part of a larger nationalist project — a time when defiant anthems celebrating cultural identity and independence were not commodities to be traded while great cities burned.

Catch the exhibition in London through Aug. 23 or wait until Al Qassemi’s plans to take it around the world materialize. This constellation is guaranteed to dazzle.

Hadani Ditmars is the author of Dancing in the No-Fly Zone: A Woman’s Journey Through Iraq, a past editor at New Internationalist, and has been reporting from the Middle East on culture, society, and politics for two decades. Her book in progress, Between Two Rivers, is a travelogue of ancient and sacred sites in Iraq.

Photo by Sueraya Shaheen

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.