In October, the United Nations embargo on arms sales to Iran is scheduled to expire. This was a deadline specified in the 2015 Iran Nuclear Deal concluded by the Obama Administration. The Trump Administration stridently opposes the lifting of this restriction and is lobbying within the UN Security Council to have the embargo extended indefinitely.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has taken a hard line for this arms embargo to remain in place. On 23 June, he tweeted that should the embargo expire, “Iran will be able to buy new fighter aircraft like Russia’s [Sukhoi] Su-30SM and China’s [Chengdu] J-10. With these highly lethal aircraft, Europe and Asia could be in Iran’s crosshairs. The US will never let this happen.”

The cynical view is the Trump Administration opposes the lifting of the arms embargo for two reasons. One is that the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), more commonly known as the Iran Nuclear Deal, is another one of the previous Obama Administration’s policy accomplishments that today’s White House would like to see dismantled and binned. The other is that in an election year it never hurts an American president to be beating the drum against the usual cast of bogeymen – Russia, China and Iran.

The reality is that there is actually a serious narrative around why Iran acquiring the latest weapons in the Russian and Chinese arsenals could have some very serious negative ripple effects. It is a long story that begins with the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

For three decades now, one of the entities most nervous about Iran being able to purchase the latest in Russian weapons technology – specifically long-range anti-ship missiles (ASM) – has been the US Navy. The problem is a simple one, as US Naval Intelligence officials explained as early as 1992: “If the Iranians acquire some of the more long-range, supersonic [Russian] ASMs we can no longer safely deploy a carrier in the Persian Gulf.”

Lest anyone forget, the entrance to the Persian Gulf is the Strait of Hormuz, a narrow chokepoint leading to this body of water through which some 20 percent of the world’s oil passes through. If no carriers can enter the zone, then the world could be held hostage to the erratic impulses of the Iranian Islamic Republic.

More than a quarter of a century later, there are three reasons to believe that this dilemma created by Iran achieving Anti Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) against the US Navy’s carrier fleet is more of a concern than ever before.

The PRC Missile Factor

The first is that Iran has not made the purchases of ASM technology from Russia that so many in the Pentagon and Naval Intelligence had dreaded, but that is not the end of the story. Instead, since the early 2000s, the country has been in a very quiet, and thinly-reported partnership with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the development of ASMs of differing ranges and flight profiles.

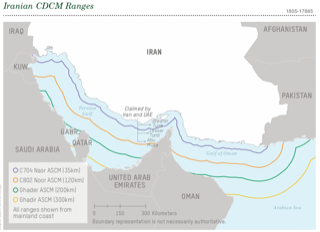

The acquisition of these missiles and their placement along the coastline by Iran mirrors deployments made by the PRC’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in the South China Sea. The purpose is to create a layered defense of multiple threats against US Navy capital ships. These missiles - which can be launched from land, sea and air - are the product of almost 20 years of defense industrial partnership between the two nations.

Although originally of Chinese design, these missile systems are produced in Iran by what has been called the “Cruise Missile Systems Industries Group,” which appears to be part of the Iranian Aerospace Industries Organisation (AIO).This entity is one of the several major industrial groupings that constitute Iran’s state-owned arms manufacturing base.

The various designs originated with the PRC’s Hongdu Aviation enterprise and were first seen in November 2002 at Air Show China, held in Zhuhai, Guangdong Province. However, they were presented without any mention of the fact that they had been designed initially not for the PLAN, but for the Iran military as the primary customer.

The obfuscation of just where these missiles have ended up and their mission combat profile has been aided by the fact that the Iranians use different designators than the original Chinese nomenclature associated with these model numbers. That association is seen here:

| Iranian Designator | Chinese Designator |

| Kosar-1 | C701T |

| Kosar-3 | C701R |

| Noor | C801/802 |

| Kosar | JJ/KJ/TL-10 (derivative of older FL-8 programme) |

| Nasr | JJ/TL-6 (identical to what was once FL-9)/C704 |

The placement of these assets - what US intelligence refers to as Coastal Defense Cruise Missiles (CDCM) - and their ability to hit targets in the Persian Gulf can be seen in a graphic presented in the US Defense Intelligence Agency’s (DIA) 2019 report, Iran Military Power.

How To Sink an Aircraft Carrier

The second factor is that in recent years Iran has been putting considerable effort into rehearsing how to attack and sink a US aircraft carrier in the Gulf. This includes Iran building a subscale replica of a US Nimitz-class carrier, which is the target platform for these exercises. The most recent of these carrier mockup models has been seen at the port of Bandar Abbas in satellite passes during the last two months.

Photo interpreters looking at satellite images of the latest Iranian mockup estimate the target vessel to be 200 meters (650 feet) long and 50 meters (160 feet) wide. This is slightly smaller than a full-size Nimitz-class carrier, which is over 300 meters (980 feet) long and 75 meters (245 feet) wide.

On 28 July, Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the entity that has been actively engaged in training deployments to simulate attacking and sinking a US carrier, launched underground ballistic missiles at this model of a Nimitz-class carrier. Using the ballistic missiles in conjunction with their other assets creates a new dimension that Iran’s military would bring to bear against a US Navy task force.

The Iranian state TV network, IRIB, carried coverage of this exercise on its website, stating “An important achievement of the IRGC’s aerospace [forces] at this stage of the exercise, the successful firing of ballistic missiles from the depths of the ground was completely camouflaged, which could pose serious challenges to the enemy intelligence agencies.”

Moreover, this is not the first time for this exercise. A previous set of A2/AD manoeuvres conducted by the IRGC called Prophet 9 against the same type of carrier mockup took place in February 2015. At the time, the exercise was interpreted by some to be a bit of theatre to strengthen Tehran’s hand in the negotiations in the Nuclear Deal negotiations.

The DIA, however, assessed that this was the Iranian armed forces genuinely building an anti-carrier set of operational capabilities. The 2019 report reads:

Iran emphasizes asymmetric tactics, such as small boat attacks, to saturate a ship’s defenses. The full range of Iran’s A2/AD capabilities include ship- and shore-launched antiship cruise missiles (ASCMs), fast attack craft (FAC) and fast inshore attack craft (FIAC), naval mines, submarines, UAVs, antiship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), and air defense systems.

Iran’s maritime A2/AD strategy employs a combination of surface combatants, undersea warfare, and antiship missiles to deter naval aggression and hold maritime traffic at risk. Particularly with its large fleet of small surface vessels—high-speed FAC and FIAC equipped with machine guns, unguided rockets, torpedoes, ASCMs, and mines—Iran has developed a maritime guerrilla-warfare strategy intended to exploit the perceived weaknesses of traditional naval forces that rely on large vessels.

What troubles intelligence analysts looking at possible hostilities in the Gulf is that the lifting of the UN embargo potentially takes away the one option the US has to neutralise Iran’s mix of A2/AD assets.

Russian and Chinese Airpower and Oilpower

This third factor that could significantly change the threat profile in Persian Gulf is the prospect of Iran acquiring the latest Russian and Chinese combat aircraft. The possibilities are very real and both nations have spared no effort in wooing Iran as a strategic defence industrial partner.

Russia has long looked at Iran as the next big “Klondike” in weapons sales, since the major exports it made to the PRC and India in the 1990s and 2000s time period have petered out and are not likely to return to their previous levels. Up until now there has not been much enthusiasm for this idea among Iran’s military-industrial complex. Many of its personnel remain enamoured of their US-made equipment.

Iran’s military remains largely equipped with military hardware purchased from the US and European nations during the reign of the Shahanshah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi (1941-79). This includes a large number of US-made Northrop F-5, McDonnell-Douglas F-4 and the Grumman F-14. Iran was the only export customer ever for the F-14 – the top fighter aircraft flown by the US Navy at the time – and required the direct initiative of the White House in order to be allowed to purchase this design.

The 1979 Islamic Revolution and the taking of hostages in the US Embassy in Tehran prompted Washington to clamp an embargo on the shipment of any spare parts to support Iran’s US-made equipment. This forced Iran’s military to set up a virtual spiderweb of networks to surreptitiously acquire the needed parts and components and reverse-engineer and fabricate other spares from scratch

The effects on the availability of these aircrafts and the attrition impact on force levels was significant. By the beginning of the 21st century, only about a third of the 76 F-14s originally purchased in the 1970s remained operational. However, in spite of any resentment the Iranians might have felt due to the hardships caused by the US denying them these spares and other assistance, the respect and admiration for US weaponry was still very strong among their military and industrial officialdom.

In late 2002 Iran held its first ever international air show in order to showcase the Islamic Republic’s aerospace industrial capability, as well as their desire to acquire new aircraft. When asked which aeroplane he wished could be the next fighter aircraft for the regular air force (IRIAF), one Iranian engineer answered, “that’s easy – the F-15.”

At the same air show in 2018, another Iranian engineer who had been involved in the early attempts to copy and manufacture an Iranian version of the F-5 stated that “the most perfect fighter engine ever designed and built is the [General Electric] F110.” On rare occasions, he continued, “everything in the engineering world comes together in a design just right so that the end result is nearly-perfect.” (The F110 is one of the most widely-used US fighter aircraft engines and is installed in several F-15 and F-16 models and also in the last of the US Navy-operated F-14D model aircraft.)

From all appearances, the days when Iran could keep overhauling ad infinitum and finding other options to keep its aging fleets of aircraft operational are coming to an end. Even those models which are still flightworthy are equipped with radars, electronic systems and weaponry that is more than two generations obsolete in some instances – creating very low survivability numbers for the pilots who fly them.

Iran has also seen the operations of some the latest Russian combat aircraft up close during operations conducted in Syria, which has been a live-fire advert for what Tehran’s military could be capable of if it acquired the same pieces of hardware. This process could well be underway at this point.

Reports earlier in July were that Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has agreed to a major foreign trade deal involving Russia and the PRC. This is a supposedly secret 25-year strategic agreement reached with Beijing - calling for some USD 280 billion to be invested by the Chinese into Iran’s oil and gas sector, most of it within the first five years.

There is also a parallel agreement that “will involve complete aerial and naval military co-operation between Iran and China, with Russia also taking a key role,” according to Iranian sources who spoke about the agreement to the energy publication OilPrice.com.

“There is a meeting scheduled in the second week of August between the same Iranian group, and their Chinese and Russian counterparts, that will agree the remaining details but, provided that goes as planned, then as of 9 November, Sino-Russian bombers, fighters, and transport planes will have unrestricted access to Iranian air bases,” according to the same source.

“This process will begin with purpose-built dual-use facilities next to the existing airports at Hamedan, Bandar Abbas, Chabhar, and Abadan,” he said. There are other reports that the bombers to be deployed will be “China-modified versions” of the long-range Russian Tupolev Tu-22M3s, and the fighters will be the medium-range Su-34 fighter-bomber, plus the newer single-seat stealthy, 5th-generation Su-57.

Chinese and Russian military vessels will be able to use newly built dual-use facilities at Iran’s ports of Chabahar, Bandar-e-Bushehr, and Bandar Abbas, all of which were constructed by Chinese companies.

These developments will reportedly be taking place in tandem with Iran’s acquisition of the same Russian Su-30SM and Chinese fighter aircraft that Pompeo had warned of in his Twitter broadcast. Both nations need export sales at a time when a combination of the economic downturn from the COVID-19 pandemic is starting to cause measurable difficulties.

Up until now, the US could argue that its superior airpower gave it the capability to knockout any of these Iranian missile emplacements and other assets that are deployed in the Gulf. However, should Iran acquire advanced platforms from Russia and China and a parallel set of air defense batteries as well, this would no longer be a given. Trying to prevent the UN from permitting these arms sales from happening is not just election-year grandstanding. It has some severe implications for the future of the US military and its presence in the Middle East.

Reuben F. Johnson is a defense technology analyst and political affairs correspondent based in Kiev and has reported on Iranian defense technology developments for more than two decades. He writes for numerous publications, including the journal European Security and Defence and the public affairs news service, the Washington FreeBeacon. The views expressed here are his own.

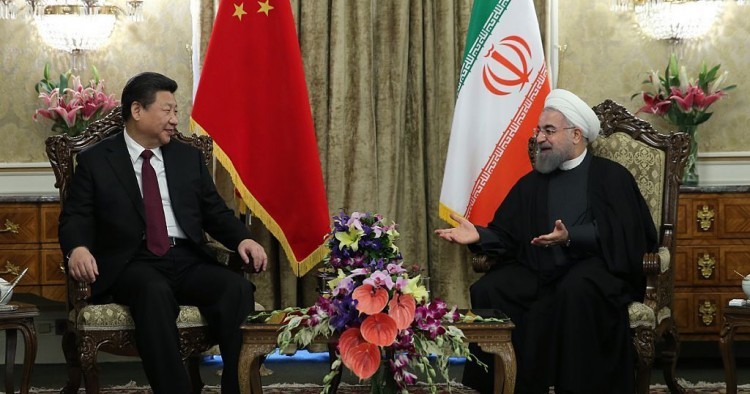

Photo by Pool/Iranian Presidency/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.