Egypt is currently the fastest-growing Arab exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG), according to a report released by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) on Aug. 16. The report showed that Egypt exported around 1.4 million tons of LNG in the second quarter of 2021, having not exported any LNG during the same period in 2020.

Egypt contributed about 5% of Arab countries’ total LNG exports, which amounted to 28.3 million tons in the second quarter of 2021. Despite Egypt’s relatively small contribution to the total, it represented the largest percentage (47%) of the growth of Arab LNG exports during the second quarter of 2021, which were up from 25.3 million tons in the same period a year earlier.

The OAPEC report follows many studies predicting that Egypt would become a major player and a prominent competitor in the global LNG market, and this article will analyze the factors supporting this assessment.

A look at the numbers

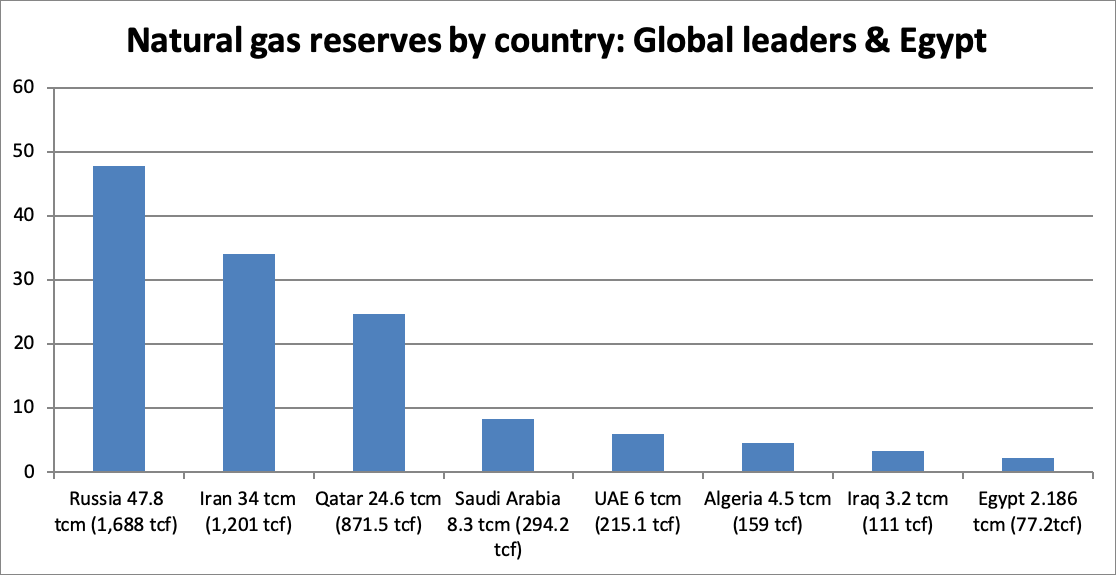

Egypt has 2.186 trillion cubic meters (tcm) or 77.2 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of proven natural gas reserves, according to BP and the U.S. Energy Information Administration, placing it 16th in the world. These reserves are equivalent to around 1.6 billion tons of LNG.

In the abstract, this figure may seem huge, but it does not put Egypt among the leading Arab countries in terms of natural gas reserves, such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Algeria, and Iraq. The Middle East also has a gas-rich non-Arab country in Iran. At the global level, Russia tops the list with reserves of 47.8 tcm or 1,688 tcf.

Limited domestic consumption is one of the characteristics of many leading natural gas producers and exporters. However, this is not true of Egypt, which consumes 158 million cubic meters (mcm) or 5.6 billion cubic feet (bcf) of gas per day, compared to Qatar and Algeria’s daily consumption of around 96 mcm and 118 mcm (3.4 bcf and 4.2 bcf), respectively.

Regional dynamics

Egypt can be considered a special case in terms of natural gas production and export. It does not derive its current position as an emerging LNG exporter or its prospective one as a major player in the gas market from its production or huge reserves, as most significant LNG-exporting countries do. Rather, its standing is a result of being surrounded by smaller exporters, its untapped gas liquefaction potential, and its close ties with the EU.

Egypt’s close geographical proximity to both Cyprus and Israel, which aspire to export their surplus gas production to Europe, encouraged the conclusion of agreements between each of them and Egypt. These agreements state that Cyprus and Israel will export their surplus to Egypt’s gas liquefaction complexes in Idku and Damietta, with Egypt then liquefying it and exporting it on to the EU. Negotiations are also taking place between Egyptian and Greek officials on how to cooperate in the field of liquefaction.

Projects to link natural gas producing and exporting countries in the Mediterranean have become common in recent years. The most prominent of these is the EastMed gas pipeline project. EastMed is expected to link the gas fields in Israel and Cyprus with Greece, which will transport it to European markets through its two pipelines: the Gas Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IGB), linking Greece with Bulgaria, and Poseidon, which connects Greece with Italy.

However, EastMed has been a source of controversy regarding its prospects for success compared to the gas linkage projects in which Egypt participates. Local and international observers have questioned its feasibility, given the lack of gas liquefaction plants in the participating countries — Israel, Cyprus, Greece, Bulgaria, and Italy — and the fact that most European markets, the main destination for exports, currently prefer LNG as an alternative to pipelined gas, in line with the European Commission's LNG and gas storage strategy.

According to the strategy, LNG allows EU countries to diversify their mix of suppliers and reduce their reliance on a handful of producers that export gas through pipelines, most notably Russia, which covers 39% of the EU's imported gas needs. In addition, unlike compressed pipeline gas, LNG can be stockpiled, helping the EU to protect itself against any possible supply interruptions that may occur due to political or economic disputes with suppliers.

Analysts also note that connecting Europe to more suppliers through pipelines, like EastMed, can be both costly — in terms of initial construction as well as ongoing safety and maintenance — and time-consuming compared to importing LNG.

By contrast to the EastMed countries, Egypt still has unutilized gas liquefaction capacity to produce 12 million tons of LNG annually through the Idku and Damietta liquefaction complexes, which are able to fully operate again in 2021 after remaining idle for eight years.

A lack of substantial liquefaction capacity is the reason why Iraq is not competing in terms of gas exports to Europe; despite its significant reserves, it can only produce 6,000 tons of LNG per day, or 2.19 million tons per year, according to an April statement from the Iraqi Ministry of Petroleum.

The availability of unutilized liquefaction capacity does not distinguish Egypt only from the EastMed countries and Iraq though. It could also be one of Egypt’s competitive edges over countries such as Russia and Algeria, especially if the focus is on exports to European countries, which currently prefer LNG.

Russia's exports of LNG indicate that it is currently utilizing 100% of its gas liquefaction capacity, while Algeria is expected to expand its utilization to compensate for losing the ability to export part of its gas to Spain via the Maghreb-Europe Gas Pipeline, which passes from Algeria to Spain through Morocco and the Strait of Gibraltar, after it cut diplomatic relations with Morocco in August 2021.

According to Statista, LNG constituted only 17% of Russia’s total exports of natural gas, which depend heavily on gas pipelining, and made up just 37% of Algeria’s total gas exports in 2020.

Moreover, Egypt has a long history of stable relations with the EU, unlike Russia, which has been economically sanctioned by the bloc since 2014 due to its military intervention in Ukraine.

As for Iran, despite its abundant gas reserves, the sanctions imposed by the U.S. on any country or entity dealing with it marginalized its role as an exporter of oil and gas to Europe. This looks to remain the case, at least for now, as negotiations in Vienna between the country and the U.S. to restart the 2015 nuclear deal — which could free Tehran from these sanctions — have faltered.

Sanctions against Iran may also weaken Qatar’s position as one of the leading regional LNG exporters to Europe. Qatar’s plans to increase its yearly production of LNG to 126 million tons by 2027, up from 77 million tons at present, largely depends on output from the South Pars/North Dome gas-condensate field, which it operates jointly with Iran. In this case, this field is expected to contribute around 39% of Qatar’s total LNG production.

Outlook

In light of the above factors, Egypt seems likely to play a key and growing role in meeting the EU’s LNG needs, especially given that the country’s surplus natural gas production could reach 1.6 bcf per day in 2021, on production capacity of 7.2 bcf compared to consumption of 5.6 bcf.

If maintained, this would translate into an annual surplus of 16 bcm or 584 bcf, enough to produce 12.2 million tons of LNG based on current liquefaction capacity, even without partnerships with Cyprus, Greece, or Israel. This represents around 15% of the needs of the EU, which imported 108 bcm of LNG — about 80 million ton — in 2019, according to the latest figures published by the European Commission.

Ahmed Fouad is an Egyptian journalist and analyst. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Dana Smillie/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.