This article first appeared in Foreign Policy.

In April, Egyptian graphic novelist Magdy el-Shafee went to Abdel Moneim Riad Square in downtown Cairo to protest a draft law put forth by the Muslim Brotherhood's political arm, the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP). It would only be two months until the Brotherhood president, Mohamed Morsi, would be ousted by the Egyptian military.

The law in question aimed to "purge" the Egyptian judiciary of more than 3,000 judges, most of whom were appointed during the regime of Hosni Mubarak. Many in Egypt, including el-Shafee, saw the Brothers' proposed law as just another attempt to ensure themselves sweeping powers, à la Mubarak. One aspect of these powers that alarmed much of the Egyptian public was the repression of journalists, authors, and artists for critiquing the state, which has carried across regimes.

"I went peacefully," el-Shafee recalls. "Police surrounded us, and they caught me and beat me." He was arrested with 39 other activists and spent four days in Tora Prison before being released on bail. El-Shafee's case is still pending; overblown charges against him include carrying a weapon, the attempted murder of three police officers, and destroying public facilities.

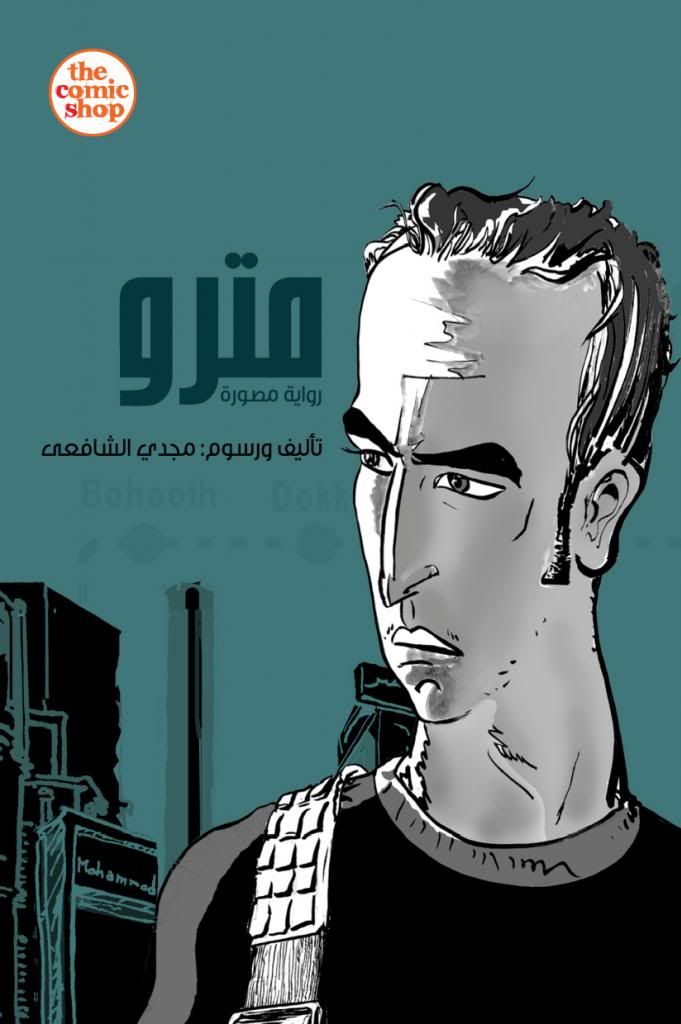

It was the not the first time that el-Shafee had been taken by police, however. In 2008, Mubarak's regime detained and questioned him about his first and most famous work, the graphic novel Metro, whose critical depictions of the authoritarian state did not endear him to those in power. The book was banned and el-Shafee fined around $700.

While the circumstances surrounding the two arrests are rather different, they are indicative of the culture of fear and repression that has prevailed in Egypt both before and after the fall of Mubarak. The calls for "bread, freedom, and social justice," including freedom of expression, that were chanted in Tahrir Square in 2011 have not been met. And with the military now in power, a different and perhaps more sinister kind of repression is permeating Egyptian society -- one due to a fervent nationalism in which the intelligentsia and the media punish those who dare to publicly criticize the generals.

Such events have affected el-Shafee deeply. "I am not producing work," he tells me. "I feel paralyzed."

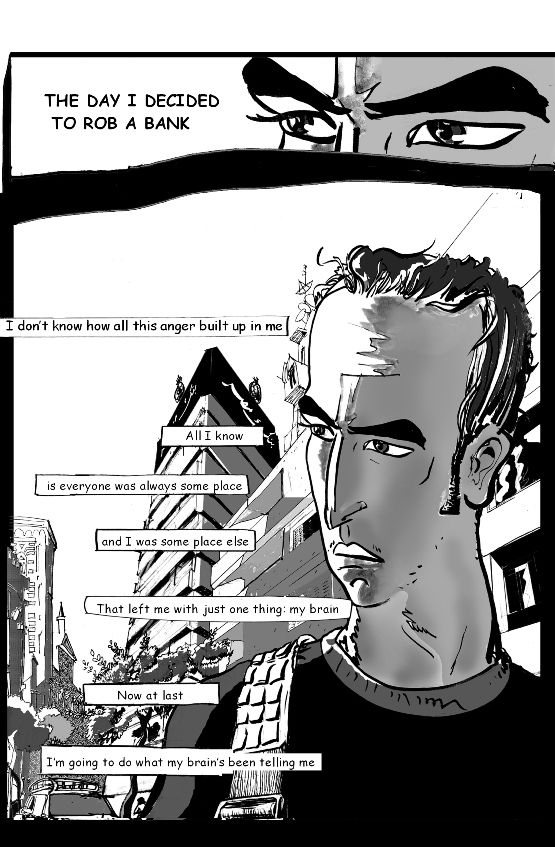

El-Shafee's Metro is considered Egypt's first graphic novel, and el-Shafee is often referred to as the Egyptian godfather of the genre. Metro tells the story of two young men trying to outsmart a corrupt and violent Mubarak-era Cairo by robbing a bank. It chronicles police crackdowns on antigovernment protesters, including sexual harassment, as well as shady dealings among government officials and businessmen. The novel's moody, dark atmosphere -- both in written content and artistic style -- show a Cairo on the verge of explosion. "We're all living in one big cage," Shehab, the protagonist, observes. "The cage is open, but nobody leaves...We all have to leave the cage together."

El-Shafee's Metro is considered Egypt's first graphic novel, and el-Shafee is often referred to as the Egyptian godfather of the genre. Metro tells the story of two young men trying to outsmart a corrupt and violent Mubarak-era Cairo by robbing a bank. It chronicles police crackdowns on antigovernment protesters, including sexual harassment, as well as shady dealings among government officials and businessmen. The novel's moody, dark atmosphere -- both in written content and artistic style -- show a Cairo on the verge of explosion. "We're all living in one big cage," Shehab, the protagonist, observes. "The cage is open, but nobody leaves...We all have to leave the cage together."

Under Mubarak's ban Metro was only available in Italian and English, but in August 2012 -- under the Brotherhood -- it reappeared in bookstores in its original Arabic. While it's possible that the Morsi regime allowed the return of the book, being all too happy to support negative depictions of its former opponent, it's more likely that the chaotic, less regulated atmosphere of publishing post-Mubarak had more to do with it. At the time, a rumor of banning a book would be met with a firestorm of criticism and a surge in demand. "Though a lengthy list of banned titles still existed," says Egyptian-Canadian media scholar Adel Iskandar, "bans were easy to circumvent."

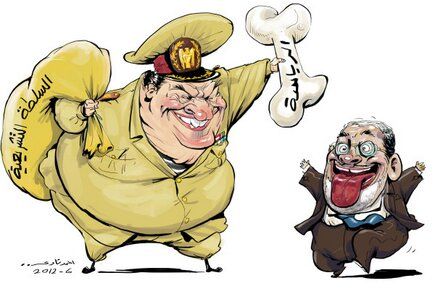

And in realms beyond book publishing, Egyptians saw and read things that they never would have -- at least publicly -- before 2011. Jonathan Guyer, a Fulbright scholar studying Egyptian political cartoons, sent me a number of examples, such as one by Ahmad Nady from 2012's election period. It shows the military holding a bone named "presidency" over Morsi, who is rendered in an undignified, dog-like paroxysm of excitement at being granted the chance to rule. Other Nady works show more grotesque illustrations of the president, such as Morsi tweeting while on the toilet. "You would never have seen that five years ago," Guyer says.

Despite these openings, the Brotherhood regularly suppressed artists, writers, media personalities, and others for creating "offensive" content. One such crackdown occurred in March at Media Production City, where Brotherhood members and sympathizers blocked journalists who they saw as critical of Morsi from entering the complex of television studios. Another much talked-about case was that of Bassem Youssef, in which the television satirist (often compared to the American Jon Stewart) who frequently poked fun at the president on his show al-Bernameg was questioned by Egypt's general prosecutor for insulting Morsi and Islam.

Soon before Morsi's demise, more repressive book publishing cases were appearing as well, signaling the Brotherhood's tightening reins on printed content. In June, author Karam Saber, who had published a book of short stories titled Where is God? two years prior, was sentenced to five years in prison by a court in Beni Suef for "insulting religion." And the May appointment by the Brotherhood of culture minister Alaa Abdel-Aziz signaled to many a suppression of freedom of expression on a broader scale. After the appointment, dozens of artists, writers, and filmmakers staged a sit-in at the Ministry of Culture to protest the new minister's policies, which they said sought to censor creative work and included the firing of the heads of the Cairo opera house and Egypt's general book authority, ostensibly to bring in more Brotherhood-friendly figures.

Now, with Morsi and other Brotherhood leaders under arrest and the continuation of military crackdowns on Brotherhood protests, much of Egypt seems enamored of and thankful to the army. Widespread adoration for the head of the armed forces, General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, harkens back to the regard shown for pan-Arab nationalist and former president General Gamal Abdel Nasser in the 1950s, who also heavily suppressed the Brotherhood.

Aside from the violent deaths of hundreds of Brotherhood protesters (who, it must be said, have also displayed violence post-Morsi, notably against Coptic Christians), the military has taken swift measures to repress Islamists by, for instance, shutting down television stations and newspapers affiliated with or sympathetic to the Brotherhood, in a move eerily reminiscent of the siege on Media Production City by Brotherhood members and supporters six months ago.

"Unfortunately, Metro is still relevant," says el-Shafee. "And what we face now is a bigger problem than the Muslim Brotherhood. There is an encouragement of something like military fascism."

El-Shafee explains that the many intellectuals and public figures who support the military coup and its aftermath are publicly attacking or shaming those who criticize the army's ideology or tactics. "They will call you an agent of the West or claim that you are not nationalistic enough," he says.

One such figure under scrutiny is professor and politician Amr Hamzawy, who has taken the army to task for its use of violence to disperse Brotherhood sit-ins. He wrote in a recent op-ed, "[The media] accuse of treason anyone who opposes...the intervention of the army in politics or anyone who refuses to be silent about human rights violations...All of this is happening to me."

While the military may only be enjoying a honeymoon period among the citizenry that will end soon enough -- after all, Egyptians called en masse for the removal of the military from its 18-month rule after Mubarak's ouster, in 2012 -- the current atmosphere in Egypt is one that propagates fear of speaking out against the new status quo. Yet what makes the situation more disturbing than what occurred under Mubarak and Morsi is that citizens are more apt to police each other in addition to being policed by a central power and its security services -- creating an atmosphere in which el-Shafee understandably feels creatively paralyzed.

El-Shafee and others who place themselves outside powerful groups can only hope that dissent against any power, whether the Brotherhood, the military, or the remnants of the Mubarak regime, will be tolerated and, indeed, celebrated in the near future.

"The transition [to greater freedom of expression] will take awhile," he says. "The country and I are in a transition state," he adds, joking, "so maybe if I move faster and find momentum in my work, the country will follow."

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.