The MENA Energy Recap is a quarterly review of key energy developments that took place in the region from July through September of 2025 and what they signal in the months ahead. The Recap views these developments through the lens of policy and strategy, energy security, and markets.

Q3-25 in Brief:

Across the Middle East and North Africa region, events in Q3 point toward geopolitical factors continuing to play a larger role in regional energy trade dynamics, with varying impacts across specific areas. Ostensibly helped by US efforts, the Iraq-Turkey Pipeline (ITP) reopened after more than two years of inactivity, reenabling oil exports from the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in northern Iraq after a long suspension. Yet in Israel, pressure by the United States has done little to move the government closer to approving a $35 billon deal that would see Egypt import more Israeli natural gas. This raises the question of whether developments in the Middle East are now testing the limits of the “Trump factor” and its ability to direct certain outcomes in the sector. With energy demand across MENA continuing to rise — and set to increase by as much as 50% over the next decade in the electricity segment, according to one estimate — energy security will be top of mind for import-dependent countries looking to avoid shortfalls.

In Q2, the MENA Energy Recap highlighted continued momentum behind Gulf national oil companies (NOCs) and their efforts to make strategic acquisitions across the global oil and gas value chain. This trajectory does not appear to have slowed in Q3, even with what would have been Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) subsidiary XRG’s largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) acquisition to date falling through. While Gulf NOCs are clearly seeking to become much larger stakeholders in the global industry, new risks will undoubtedly emerge as they continue to advance this strategy.

Energy Security, Policy and Strategy: Egypt-Israel Gas Trade Embroiled in Regional Tensions

-

On August 7, the partners operating Israel’s flagship Leviathan natural gas field announced a 15-year, $35 billion agreement to double existing exports to Egypt. Yet in early September, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu paused the export arrangement, reportedly over disputes with Cairo’s military presence in the Sinai and its position toward the conflict in Gaza.

-

Israel has been largely supportive of growth in its gas sector since it first began making significant discoveries in 2000. What makes the pause notable is that Netanyahu, who has held office for a majority of that period, had never previously taken any policy decisions that seriously hindered the industry’s growth. While shifts in the Israeli political landscape post-October 7 clearly play some role, the move marks the first time the gas trade has been caught in the political crossfire since that watershed moment.

-

November 30 is the current self-imposed deadline set by Chevron and its partners at Leviathan, which is set to provide the additional, incremental flows that Egypt would import as a part of the deal. Should this date come and go without a resolution and lead to the deal being abandoned, this would represent one of the largest politically induced setbacks to gas development in the Eastern Mediterranean in years.

Outlook: Israel’s natural gas sales to Egypt have been touted as a model of how regional energy trade can flourish in spite of tensions or disagreements on other key policy issues, and even serve as a tool to support Israel’s efforts to normalize ties with other MENA states. Mubadala Petroleum, the energy investment arm of the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund Mubadala, purchased a 22% stake in the Tamar field in 2021, eventually divesting down to 11% due to regulatory issues. The discovery of offshore gas reserves whose output far exceeds domestic demand for this fuel has been a boon for Israeli energy security, opening up commercial opportunities for the local gas sector to export excess volumes to neighboring Jordan and Egypt.

Nowhere has Israeli pipeline gas been more critical than Egypt. Cairo has taken a supply-side approach to meeting what often appears to be an insatiable appetite for more gas and electricity: demand only continues to grow while domestic output struggles. Cairo has been ramping up expensive cargoes of imported LNG, but pipeline imports represent a more cost-effective option. Egypt’s access to more affordable gas imports is thus highly dependent on its ability to increase purchases from Israel.

On the Israeli side, both foreign policy matters and domestic energy issues have emerged as major obstacles to the deal’s approval. Negotiations over the price of natural gas from Tamar, another of Israel’s key offshore fields, have led Energy Minister Eli Cohen to threaten that all applications for new gas exports will be frozen if Israeli consumers are hit with a hike in electricity prices. Whether this additional challenge is linked to Netanyahu’s initial opposition to further exports is unclear, but the ultimate result remains a deterioration in the above-ground risk outlook for international oil companies (IOCs) operating in Israel’s upstream, as well as a potential threat to Egypt’s energy security. Yet Egypt’s procurement of multiple floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) has bolstered its ability to import LNG. Combined with existing import agreements from Israeli gas producers, this significantly reduces the likelihood that Egypt will experience the kind of gas supply shortfalls it has faced in the past, even if such an arrangement is less cost-effective than importing greater volumes of Israeli gas.

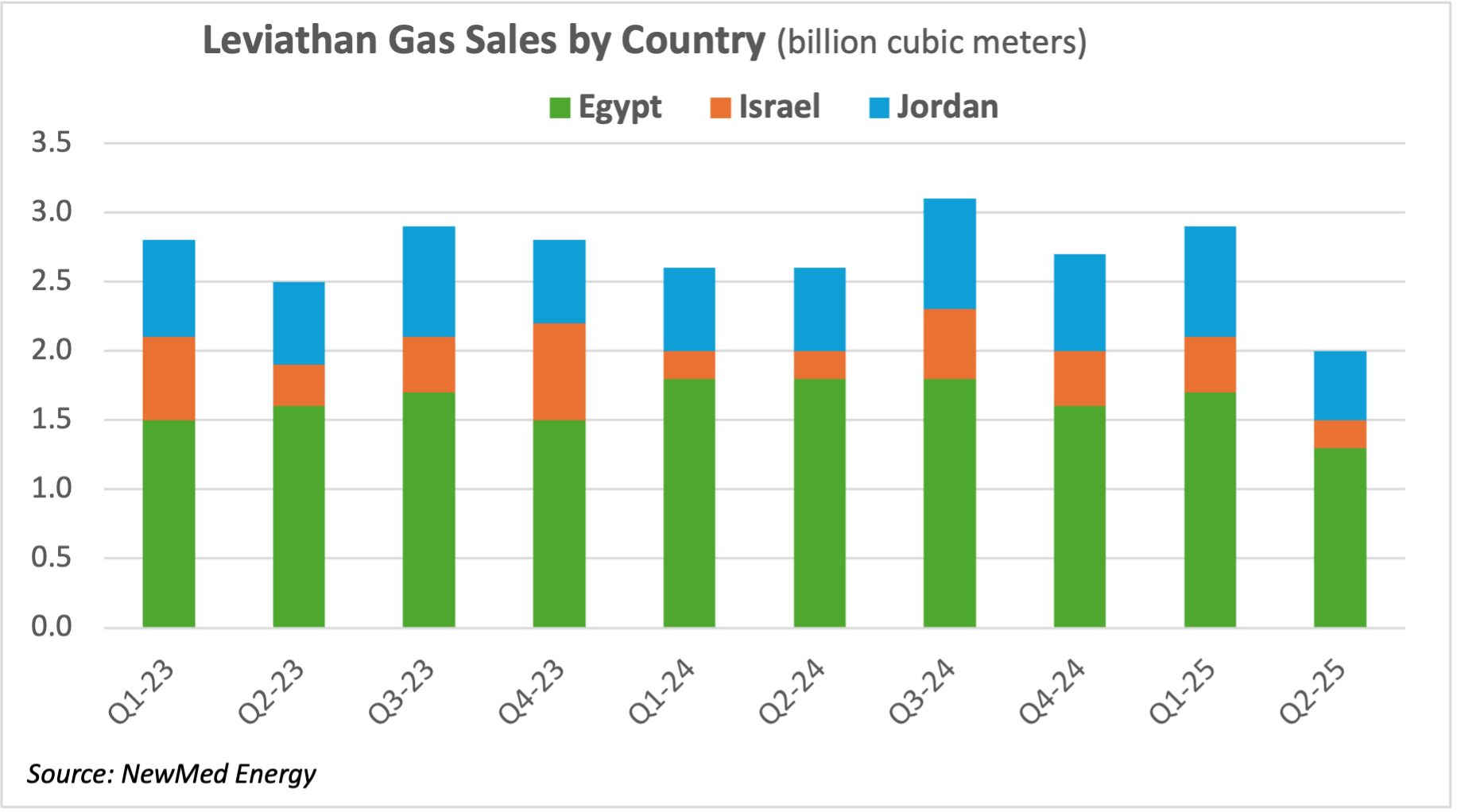

Despite uncertainty over the major new export agreement, the natural gas trade between the two countries has become an increasingly codependent relationship. The critical role of Israeli gas in shoring up Egyptian energy security is a factor that this publication has noted in the past. However, the failure to close this deal would present Israel’s gas sector with an uncomfortable reality, which is that it has become overly dependent on Egypt as a destination for its exports. In the first half of 2025, 62% of output from the Leviathan field alone was exported to Egypt. Full-year results from NewMed Energy revealed that in 2024, flows to Egypt accounted for just under 64% of output, an increase of 7% from the previous year. To be sure, expecting further demand growth in Egypt would appear to be a safe bet for those tasked with marketing incremental volumes of Israeli gas. As Israel lacks the infrastructure to export LNG and does not have working pipeline linkages to other nearby countries, the concern that it is becoming too dependent on Egypt as an outlet for its exports is not a new one. Yet the level of impact on the Israeli-Egyptian energy trade caused by current bilateral political strains is unprecedented, especially given how largely beneficial that energy trade had heretofore been for both countries.

Moving forward, an important variable to watch will be US involvement in the arrangement. Washington strongly supports the deal between Israel and Egypt and has applied diplomatic pressure on Netanyahu to provide his blessing for the transaction to move forward, likely motivated in part by American oil major Chevron’s large presence in the Israeli gas sector. Nonetheless, US involvement thus far does not appear to have brought the deal any closer to approval. If an agreement ultimately fails to materialize, it could signify the limits of US intervention in regional energy dynamics under President Donald Trump’s administration.

Policy and Strategy, Markets: Iraq-Turkey Pipeline Reopens, but Staying Power Is Questionable

-

In a late Q3 development, the ITP reopened after more than two years of inactivity, representing a boon for the oil sector in the semiautonomous area of Iraq under the control of the KRG.

-

The reopening should result in long-sought production increases for international firms operating in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). But several persistent risk factors, including the trajectory of government formation since Iraq’s November 11 election, may threaten the durability of the agreement.

-

Rising KRI output is also likely to hinder Iraq’s compliance with the production quota set by the grouping of Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) plus major non-OPEC producers, known as OPEC+, which had been showing signs of improvement in recent months. Should OPEC+ leadership exert significant pressure on Iraq to reduce its output, this may also set the stage for new disagreements between the KRG and Federal Iraq.

Outlook: The ITP has the capacity to pipe up to 950,000 barrels per day (bpd) of crude from northern Iraq to the Turkish port of Ceyhan, where it is then loaded onto tankers and shipped to buyers around the world. When the pipeline was shut in March 2023, due to a commercial dispute between Iraq and Turkey, the KRI lost the ability to export its oil to global markets, stymieing growth in the semiautonomous region’s critical oil and gas sector. Remarkably, IOCs that operate in Iraqi Kurdistan were able to maintain production of around 280,000 bpd during the ITP outage, but much of it was sold to local consumers at prices in the $30 per barrel (bbl) range, often less than half the price Kurdish barrels would command on the open market.

The pipeline reopening ostensibly supports an outlook of growth for Kurdistan’s energy sector, as well as the establishment of a fiscal lifeline for the KRG itself and the firms that operate in areas under its jurisdiction. The deal that allowed the pipeline to restart solidifies much of the control over the KRI’s oil sector that Baghdad has sought for some time, including the provision that Federal Iraq’s State Oil Marketing Organization (SOMO) will now oversee all exports from the region. Yet following Iraq’s nationwide elections on November 11, key questions remain that may determine whether or not the ITP remains open. The extent to which the next administration in Baghdad will seek to exert further control over the KRI’s oil sector will not be clear until the new cabinet is formed. This also applies to the incoming government’s prospective stance toward talks with Ankara, which will be essential in order to reach a new agreement on ITP terms that Turkey plans to let lapse next year.

In Federal Iraq, the incumbent government of Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani has taken actions in early Q4 that tacitly confirm this uncertain outlook. Western supermajors have recently displayed renewed interest in Iraq on the heels of TotalEnergies’ landmark mega-project that was finalized in 2023. Baghdad has activated a new agreement with BP to develop the northern Kirkuk field and sought to reach terms with US firms Chevron and ExxonMobil, the latter of which exited Iraq less than two years ago. Iraq’s oil sector has suffered from an exodus of IOCs in recent years, and Sudani’s government is keen to preserve the progress it has made in winning back international investors. Early assessments of the November 11 elections suggest Sudani’s coalition won a plurality of seats, putting him in a strong position to renegotiate the ITP deal, should he head the next government. The energy sectors of both Federal Iraq and the KRI may be well positioned for further progress, but political factors will significantly cloud this outlook until the dust from the elections has settled.

Energy Security, Policy and Strategy: IEA Electricity Outlook Confirms Regional Growth Trends

-

A Q3 report from the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that electricity demand across MENA will grow an additional 50% by 2035, highlighting that while energy markets are a key determinant of the region’s economic outlook, local demand is a factor whose importance will only increase alongside regional economic growth.

-

Although the report identifies which countries in the region drove most demand growth over the past 23 years, it provides little insight on country-specific growth for the next decade, focusing instead on sectoral drivers of demand.

-

As noted in previous editions of the MENA Energy Recap, there is a continually widening disparity between those regional consumers well positioned to meet this growing demand and those that are likely to be increasingly constrained by it.

Outlook: Electricity demand in the MENA region tripled from 2000 to 2023 to reach 1,440 terawatt-hours (TWh), according to an IEA report released during Q3. The overwhelming majority of this was accounted for by just four countries, with Saudi Arabia and Iran each representing 25% of the region’s demand growth, and the United Arab Emirates and Egypt each contributing an additional 10%. The report goes on to detail a number of initiatives on a country-by-country basis that are expected to continue driving power demand growth, touching on the need to satisfy greater requirements around cooling and water desalination. Elsewhere, demand will be further supported by strategic economic initiatives that are highly energy intensive, such as the development of data centers in Saudi Arabia and the UAE along with selective buildouts of electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

Those dynamics aside, subsidized energy pricing will remain a key factor stimulating regional demand growth over the next decade. A recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) publication exploring this issue notes that subsidies on both natural gas and electricity have kept prices at levels that are around half of the global average — and that is despite the fact that a number of MENA countries had moved toward subsidy reforms in recent years. Notably, most of these reforms were undertaken in oil- and gas-exporting countries like Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, and the UAE.

Subsidy reforms are often a politically sensitive issue that must be managed carefully. Rolling back government price assistance too fast typically results in a sharp increase in energy costs, which is in turn felt most acutely by low-income households if the reform legislation is not tailored to protect them. Most MENA countries that have advanced subsidy reforms have sought to avoid a haphazard rollout, yet mismanagement of this process can have dire consequences: in 2020, an Iranian measure that cut fuel subsidies resulted in prices spiking as high as 200%, leading to protests and a forceful government response that left more than 200 dead.

The IMF notes that when it comes to subsidy reform, laggards include a number of oil and gas exporters, such as Algeria, Libya, and Kuwait, the latter of which experienced power outages this past summer, partly brought about by overconsumption that exceeded the limits of domestic power-generation capacity. While the IEA’s report highlights demand growth brought about by advances in economic diversification in more energy-secure parts of the region, many of which are in the Gulf, the IMF points out that many other MENA countries may face energy security and fiscal challenges so long as demand continues to grow on the basis of artificially low prices that weigh heavily on national budgets.

Policy and Strategy: Gulf NOC Acquisition Push Brushes Up Against Ownership Concerns

-

In September, ADNOC subsidiary XRG’s efforts to acquire Australian LNG heavyweight Santos fell through — a deal that would have been its most significant international LNG acquisition to date.

-

At around the same time, Saudi Aramco increased its LNG exposure by raising its stake in MidOcean Energy to 49%, highlighting the differentiated approach that Gulf NOCs are taking to become more competitive players in the global LNG landscape, in which Aramco’s presence was previously limited to trading activity.

-

Notably, XRG’s interest in Santos revealed that new political risk factors may emerge as Gulf NOCs continue to seek out major new investment opportunities overseas.

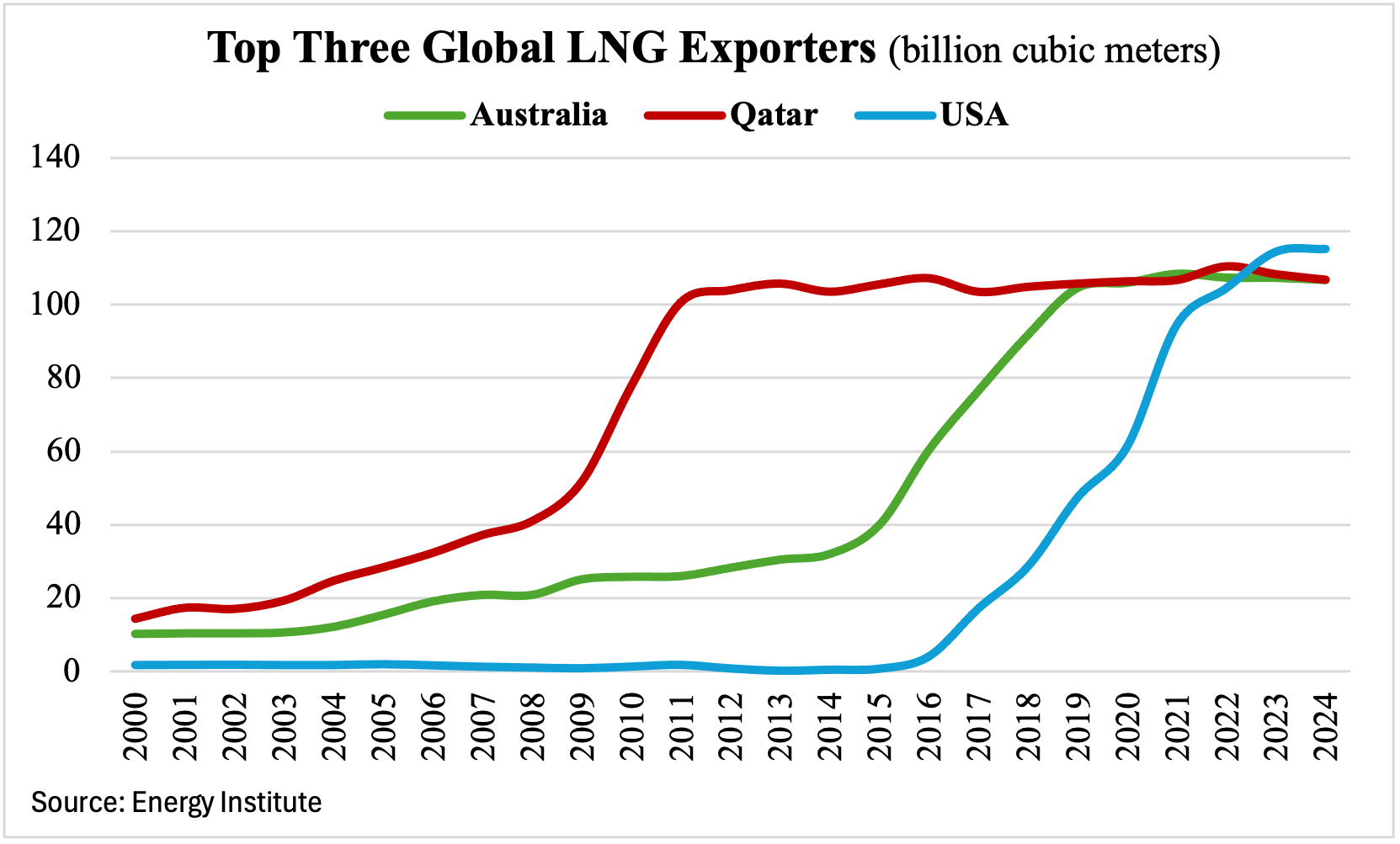

Outlook: XRG’s acquisition of Santos would have turned parent company ADNOC into a much more significant player in global LNG markets with the stroke of a pen. Its portfolio includes 23.8 million tons per annum (mtpa) in LNG capacity across Australia and Papua New Guinea, an equity stake that would have made a major contribution to XRG’s target of building its own LNG capacity out to 20-25 mtpa by 2035. XRG would not have been the first Gulf NOC to enter Australia; Saudi Aramco already controls a 49% share in MidOcean, and the Kuwait Petroleum Corp.’s global upstream arm KUFPEC has held a 13.4% stake in Chevron’s Wheatstone LNG project since 2009. Still, XRG’s acquisition of Santos would have been the largest such entry to date, making the firm a significant player in one of the three largest LNG-producing countries worldwide, which exported just slightly less than Gulf LNG heavyweight Qatar in 2024.

After both XRG and Aramco signed up for investments in US LNG projects in 2024, it seems only rational that Australia might be the next destination for Gulf firms looking to build out a truly global, competitive LNG portfolio.

XRG ultimately decided to walk away from the Santos acquisition. The firm encountered a new risk factor in Australia that it had not faced when buying sizeable stakes in US LNG projects: local concerns and potential opposition to foreign state-owned entities acquiring key domestic players. In a notable precedent for this in Australia, Shell was blocked from acquiring Woodside, another major local energy firm, in 2001. XRG notably faced similar (although not identical) concerns in its bid to acquire German petrochemicals giant Covestro, although recent reports suggest a European Union probe of the transaction is likely to conclude in XRG’s favor. Nonetheless, as Gulf NOCs continue to seek out new investment destinations around the world, events in Q3 point to the potential need to navigate risks stemming from these concerns.

Outlook for Q4-25

While above-ground risk factors ultimately led to the reopening of the Iraq-Turkey oil pipeline, they also appear to be a major hindrance to growth in natural gas flows between Israel and Egypt. As discussed in the previous section, relations between Baghdad and Ankara will prove key to the two countries’ ability to keep crude flowing through the ITP. A new government in Baghdad will only further obscure the outlook for Iraqi-Turkish relations, as well as relations between Federal Iraq and the KRG, both of which are critical to ensuring the ITP remains operational. Since the ITP’s reopening, oil exports from the KRG-controlled territory have risen steadily, and IOCs operating in the area have disclosed plans to devote new focus to the region due to significant improvements in the operating environment.

However, while it would seem that this latest development brings plenty of ostensible benefits for both the KRG and Federal Iraq, the uncertainty over the fate of the Egyptian-Israeli gas deal suggests that this is not always enough to ensure a favorable outcome. US efforts to back the ITP reopening were likely to have played a role in the agreement, but Israel may serve as a test case for the limits of Washington’s ability to use its regional influence to secure positive outcomes in the energy sector.

Looking ahead to Q4, it is clear that Washington’s efforts to maintain influence across the region will encompass US actions in the energy sphere. The courting of American oil and gas majors by Iraq, Libya, Algeria, and potentially Syria is a sign that policymakers in the MENA region see the energy sector as a viable path to securing warmer ties with Washington, even if this is currently limited to fossil fuels. Chevron would doubtlessly benefit from the approval of more natural gas to Egypt, while US oil firms in Iraqi Kurdistan will receive a lifeline from the reopening of the ITP. In turn, Baghdad stands to gain from rising gas output in the KRI that can help reduce Iraq’s high levels of dependence on Iranian imports. What these developments have in common is that the need for greater volumes of gas is linked to electricity demand growth across the region.

While current US energy policy is largely defined by the pursuit of “energy dominance” in the realm of hydrocarbons, policymakers should not forget that building out renewable power generation capacity and other low-carbon technologies remain strategic priorities for a range of MENA countries, most of which see renewable energy as an overwhelmingly affordable and sensible option to meet rising demand. Washington, US-based firms, and, most importantly, energy consumers across the region could gain numerous mutually beneficial outcomes from such a “beyond-hydrocarbons” approach. Ignoring this sector, and other areas in which the United States can be supportive, will risk American regional energy security assistance ending up as a half-measure. Platforms to bolster forms of bilateral and multilateral cooperation already exist, but the US must not be self-limiting in the ways that it seeks to engage with the region’s energy needs.

Colby Connelly is a Senior Fellow at MEI. He is also Head of Middle East Content at Energy Intelligence, where he works with the firm’s research and editorial teams.

Top photo: A view of a Leviathan natural gas field drilling platform in the Mediterranean Sea, as seen from the Israeli northern coastal beach of Nasholim, on August 29, 2022. Source: Jack Guez/AFP via Getty images.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.