In a speech on 23 May 2013, President Obama declared the war on terror over. “We must define our effort not as a boundless ‘global war on terror,’” he said, “but rather as a series of persistent, targeted efforts to dismantle specific networks of violent extremists that threaten America.”[1] He argued that al-Qa`ida is on the run in Afghanistan and Pakistan and no longer threatens the U.S. homeland. Though he didn’t mention Yemen, Obama could well have added that he believes that al-Qa`ida in Yemen is also on the defensive and that the new government in Yemen is sufficiently stable to return the large number of Yemeni prisoners cleared for release from Guantanamo to their homeland.

With such a declaration, it would seem that Obama is pushing for a redefinition of the basis on which the United States conducts its counterterrorism efforts. After 9/11, those who saw counterterrorism as a military effort against a foreign enemy triumphed over those who saw counterterrorism as law enforcement. The Bush administration favored the war model, or at least a modified version of the military model. Congress’ Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) of 14 September 2001 allowed the United States to use military force against al-Qa`ida, the Taliban, and its affiliates. By declaring victory in his recent speech, Obama signaled that these hostilities are over and that it is time to move away from the use of AUMF as the basis of U.S. counterterrorism efforts and toward the law enforcement model.

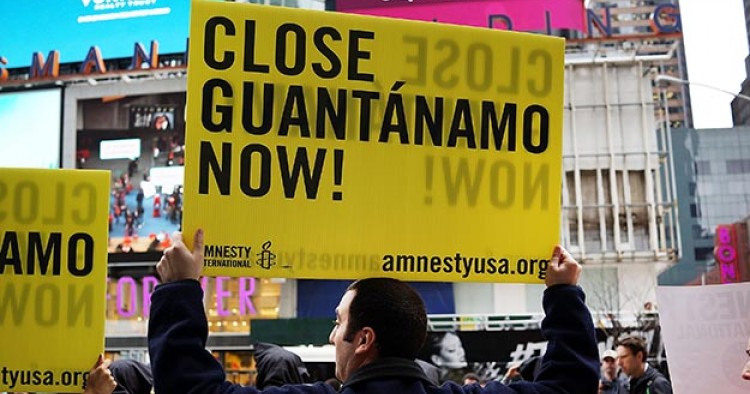

Despite these words of championing change, the reality of Obama’s quest to rethink U.S. counterterrorism, which includes closing Guantanamo and reviewing the practice of drone strikes, is mired in established policies put forward during the Bush administration that are difficult to alter. As Senator John McCain (R-AZ) commented in regard to Obama’s plan of closing Guantanamo, “[T]he devil is in the details.”[2]

Contrary to much of what one reads in the press, at issue is not the choice between the use of the military or the use of the police and civilian courts. While Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and others argue that the military must direct counterterrorism efforts and that moving prisoners from Guantanamo to U.S. soil is a non-starter unless they are in military detention, what they are really arguing for are procedures that sidestep military, criminal, and international law. “[W]e’ve got to have a legal system that recognizes the difference between fighting terrorism and fighting traditional crime,” said Graham.[3]

Both Guantanamo and the policy of targeted assassinations using drones blur the traditional division between military operations and law enforcement and create new quasi-legal precedents that circumvent many of the protections of domestic and international law. Obama’s speech signals that the president is hoping to overcome these ambiguities and set a path based in law for the future of U.S. counterterrorism efforts. Such a path would mean that drone assassinations would be run by the military rather than the CIA, that an independent review would determine which suspects to target, and that Guantanamo would close.

However, the legal ambiguities of the war on terror are not going to be easily resolved. The initial policies of the Bush administration selected or rejected the features of both international law and domestic law that best suited the administration’s objectives. The administration used the military to kill or capture suspected terrorists, detain and interrogate them as long as the “war” continued, and prosecute them as criminals but deny them the protections afforded enemy soldiers in international law or criminals in domestic law. It also argued that the United States needed to use torture (“enhanced interrogation techniques”) to extract information, hold suspects without independent review, and convict suspects in courts that did not adhere to normal standards of evidence and procedure, all of which violated U.S. military law. Thus while Graham and others argue for the use of the military, they are really arguing for special (reduced) standards of treatment for those deemed terrorism suspects.

The clearest example of this “special treatment” that is still in place is the military commissions that the Obama administration initially abandoned but restarted and is now arguing should take place on U.S. soil. Military commissions are not military courts. Military courts are subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which differs little in the key areas of standards of evidence and due process from U.S. domestic law. Instead, military commissions are courts that are run by the military but are subject to the Military Commissions Act of 2006, a Bush era revamp of the initial military tribunals the administration tried to impose in 2003 but were ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. While the military commissions have been modified to appear to adhere better to the standards used in regular military or civilian courts, they differ in standards of evidence and procedure, allowing, for example, coerced evidence, hearsay testimony, and, in some cases, secret evidence. Methods used to obtain secret evidence may not be challenged by the defendant.

The Obama administration initially wanted to abandon these special courts and transfer, for instance, Khaled Sheikh Mohammed, who was identified as “the principal architect” behind 9/11, to civilian court in Manhattan for trial. Congress forced Obama to abandon his plans, and after long delays the Obama administration opted to restart military commissions for the five 9/11 defendants as well as Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, a Yemeni national accused of being behind the attack on the USS Cole. Obama may want to close Guantanamo, but Obama is not doing away with the controversial legal innovations developed there. He is simply moving the Guantanamo courts to U.S. soil.

The Obama administration similarly argues that there are prisoners that the United States can hold without any conviction in court, or even after an acquittal in the special military commissions. In Guantanamo today there are 166 prisoners, 86 of whom the Obama administration wants to release. Of the remaining 80, it plans to try approximately a dozen of them in the special military commissions and hold the rest indefinitely—without a day in court. Were the United States adhering to the law of war and were the suspects deemed to be soldiers, the suspects could be held under international law for the duration of the conflict. Nothing in humanitarian law requires a state to return enemy soldiers to the battlefield to fight again. However, the United States denied the prisoners in Guantanamo prisoner of war status because, it argued, they are affiliated with al-Qa`ida and the Taliban—civilian organizations. Yet the terrorism suspects are also not considered civilians, and thus are not afforded the protections of Geneva or domestic law. Instead, via the Military Commissions Act, they have been labeled “enemy combatants,” a new category that does not exist in domestic or international law and therefore allows the United States to operate outside of established rules.

As a result, the United States argues that it can hold suspects without trial based solely on its determination that the suspects represent a threat to U.S. security. In a statement seemingly contradicting the detention logic, Secretary of State John Kerry argued, “Our fidelity to the rule of law likewise compels us…to end the long, uncertain detention of the detainees at Guantanamo.”[4] However, as McCain argued, the devil is in the details. Kerry is actually arguing that the United States will end the uncertain detentions in Guantanamo by moving the uncertain detentions to U.S. soil, much as Obama wants to close Guantanamo but bring the controversial military commissions to U.S. soil. As a result, nothing changes but location.

The policy of targeted assassinations follows a similar logic. The drone attacks in Yemen are far from any battle zone, as the United States is not at war with Yemen. Yet the Obama administration argues, based on the existence of AUMF or sometimes simply the right of national self defense, that it has the right to kill people in Yemen who it determines are a threat. As in Pakistan, the civilian CIA is largely directing the attacks in Yemen, not the U.S. military, so even the argument that AUMF authorizes targeted assassinations is weak. In order to bolster the legal basis of targeted assassinations, Obama called for transferring control of the operations to the military. But if Obama is ending the use of AUMF, to which he alluded in his May speech, transferring responsibility of targeted assassinations to the military only means that, again, the status quo remains, as AUMF is the legal basis for the use of the military against “terrorists.”

Likewise, the determination of targets for assassination is problematic. For years the White House has made lists of targets based on unspecified criteria and evidence, while the laws of war have very specific criteria for determining who is a target and who is not. Criminal law also determines clearly who is subject to state violence and who is immune. The White House has issued various statements justifying its determinations, but none seems to dispel the notion that the American president is creating death lists in Tuesday morning meetings. Though Obama called for greater transparency and an independent review of the targeting, any such review is still going to remain outside the framework of international or domestic law.

Thus while Obama declared in last month’s speech that he wants to end the war on terror and put U.S. policies on a stronger legal footing, in practice he remains committed to many of the quasi-legal innovations of the Bush administration that were designed to circumvent domestic and international law. Obama may achieve the symbolic closure of the prison in Guantanamo, but the legal quagmire created in Guantanamo appears to be simply changing venue rather than resolving. There are certainly some devils in these details.

[1] Peter Baker, “Pivoting from a War Footing, Obama Acts to Curtail Drones,” New York Times, 23 May 2013.

[2] Jeremy Herb, “Obama, Lawmakers Ready to Renew Push to Shutter Guantanamo Bay Prison,” The Hill, 22 May 2013, http://thehill.com/homenews/administration/301203-obama-lawmakers-ready-to-renew-push-to-shutter-guantanamo-bay#ixzz2WN5BtJcH.

[3] Herb, “Obama, Lawmakers Ready to Renew Push to Shutter Guantanamo.”

[4] Charlies Savage, “Kerry Associate Chosen for Post on Closing Guantanamo Prison,” New York Times, 16 June 2013.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.