On May 28, the Middle East affairs working group of the Russian and Chinese Ministries of Foreign Affairs (MFA) convened in Chengdu, China. The meeting was chaired by the Russian MFA’s Middle East bureau chief, Alexander Kinshchak, and the Chinese MFA’s Asian and African Affairs department head, Wang Di. In a joint statement, the Russian and Chinese MFAs acknowledged the trend toward regional reconciliation in the Middle East and vowed to “coordinate and cooperate closely on Middle East issues.”

Even though Russia and China’s strategic partnership has strengthened in recent years, the leaderships of both countries infrequently engage on Middle East affairs. Russia views China’s growing diplomatic assertiveness in the Middle East, which was evidenced by its brokering of the Saudi Arabia-Iran normalization deal in March 2023, as a positive step toward a multipolar regional order. Nevertheless, Russia is trying to avoid being completely eclipsed by China as a prospective conflict arbiter. While the two countries concur on opposing unilateral sanctions and democratic uprisings in the Middle East, Beijing does not universally approve of Moscow’s positions on regional crises and its power projection strategy.

Russia’s cautious embrace of China’s arbitration role in the Middle East

When news broke that China had brokered the Saudi Arabia-Iran normalization, Russian officials and commentators issued words of praise. Russian Presidential Spokesman Dmitry Peskov asserted that, “We welcome any steps that can and will help reduce tensions and reinvigorate dialogue in the region, in a very unstable region. Especially when it comes to such key regional players as Saudi Arabia and Iran.” Former Kremlin advisor Sergei Markov hailed the normalization as a “huge success for China” and claimed that “Russia also wins,” as China is forming an anti-American coalition. RIA Novosti commentator Petr Akopov claimed that the Islamic world was now a “strong partner” that will help Russia and China build a new world order.

Despite this effusive rhetoric, China’s diplomatic success clearly overshadowed Russia’s arbitration ambitions in the Persian Gulf. Russia has repeatedly proposed itself as a potential mediator between Saudi Arabia and Iran, and renewed this offer as recently as November 2022. Russia also unveiled its collective security concept for the Persian Gulf in July 2019, which called for multi-format dialogue between conflicting regional powers and the eventual establishment of an “Organization for Security and Cooperation in the Persian Gulf.” Russia’s proposed Gulf security body would mirror the 1991 Madrid Conference, which was co-sponsored by the U.S. and Soviet Union, and brought Israel to the table with adversaries, such as Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan.

The notion that China infringed on Russia’s traditional turf and outmaneuvered the Kremlin features in Russian media outlets. A March 10 Kommersant article noted China’s bid to “seriously intensify political activity” in the Middle East caused it to enter a zone that was previously the exclusive purview of Russia and the United States. An April 2 Lenta article went further, stating, “Both Russia and the United States are rather losers in this story: China has filled the empty space left by countries engaged in the conflict in Ukraine.” Higher School of Economics academic Andrey Zeltyn claimed that Russia’s mediation efforts were always a non-starter, as Iran saw Russia’s 2015 military intervention in Syria as a threat to its long-term hegemonic plans and would not consider Russian mediation.

To soften the prestige blow, Russian officials have framed Moscow as an inspiration and facilitator of Beijing’s mediation efforts. State Duma International Affairs Committee Chairman Leonid Slutsky claimed on March 11 that China’s mediation efforts “corresponded to the spirit” of Russia’s Gulf security plan. Slutsky also claimed that Russia’s support for the International North-South Transport Corridor, which includes Iran and Oman, would become “the most important economic superstructure atop the strategic basis achieved in Beijing.” This project seeks to create a 7,200-km corridor that will increase trade connectivity between major cities in India, Iran, Azerbaijan, and Russia, and move freight to Central Asia and Europe. Russia’s influential role in facilitating Syria’s return to the Arab League in May 2023 was a high-profile diplomatic success, which underscored its continued relevance in the sphere of intra-regional diplomacy in the Middle East.

Why a Sino-Russian alliance in the Middle East is an unlikely prospect

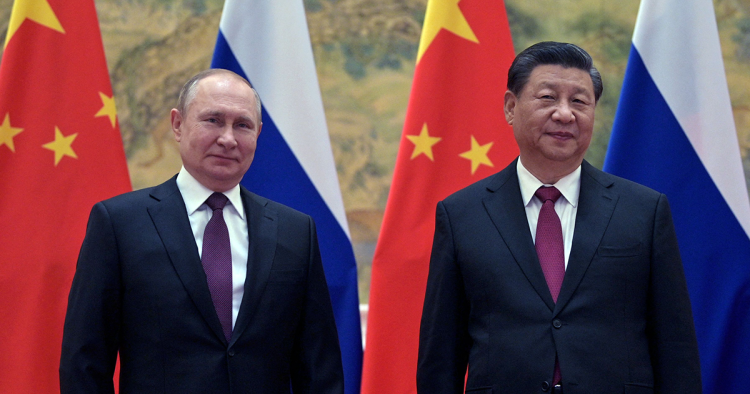

Even though Russia has a mixed view of China’s growing diplomatic influence in the Middle East, Russian officials routinely highlight the convergent views of both countries on regional affairs. On March 13, State Duma Deputy Vyacheslav Nikonov claimed that the “bankruptcy” of U.S. foreign policy helped create a “Russia-China alliance in the Middle East.” On March 21, President Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping signed a joint statement supporting “peace and stability in the Middle East” and in opposition to interference in the domestic affairs of Middle Eastern countries.

Despite this optimistic rhetoric, the scope of Sino-Russian cooperation in the Middle East is relatively narrow. In the U.N. Security Council, Russia and China have jointly opposed sanctioning Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s government for using chemical weapons and thwarted U.S. attempts to extend the arms embargo on Iran in 2020. Russia and China viewed the Arab Spring revolutions of 2011 with deep suspicion and stridently opposed the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military intervention that overthrew Libyan dictator Moammar al-Gadhafi. In June 2022, Russia and China defended Iran against the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) criticisms of Tehran’s explanations of its pre-2003 nuclear program.

These displays of solidarity mask Russia and China’s divergent perspectives on regional crises. China’s tendency to present itself as a status quo power and skeptical view of militant non-state actors reflect its stability-centric approach to Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) expansion. This contrasts with Russia’s multi-vector balancing strategy and willingness to leverage anti-systemic figures to establish geopolitical footholds. China acquiesced to the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen, which contrasted with Russia’s more critical stance and abstention from U.N. Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2216 in April 2015. China has embraced a non-aligned approach to the Libyan conflict, while Russia deployed Wagner Group private military contractors to support Khalifa Hifter’s Libya National Army. The Wagner Group’s support for Hifter’s ill-fated April 2019 offensive on Tripoli and seizure of major oil facilities in eastern Libya threatened China’s commercial interests with the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord. Despite their shared pro-Assad position, China did not join Russia in vetoing a July 2022 UNSC resolution authorizing aid deliveries across the Syria-Turkey border at Bab al-Hawa.

China also has serious reservations about the opportunistic and polarizing nature of Russia’s Middle East strategy. Andrea Ghiselli, an assistant professor at Fudan University, contends that in Beijing, “Russia is seen as an opportunistic actor whose behavior is only partially consistent with Chinese interests.” These concerns have sharpened since the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. In a July 2022 Peking University Center for Middle East studies report, Wang Lincong, a Middle East expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, admitted that the Ukraine War sharpened U.S.-China competition in the Middle East and “created uncertainties” for China’s regional influence. This view was broadly shared by the report’s co-authors, who also expressed skepticism about the potential for Sino-Russian coordination against U.S. containment strategies.

Even if Russia and China could work around these disagreements, Chinese experts are skeptical of Russia’s utility as a potential regional partner. An August 2022 Tsinghua University report authored by Degang Sun and Li Diandian declared that, “Russia is a regional power in Eurasia and has only four informal partnerships in the Middle East.” The article lists Syria and Iran as partners that “morally support” Russia, Algeria as a “passive follower,” and Sudan as a “weak informal partner.” Chinese academic Yang Cheng presents a complementary argument. In July 2022, Cheng opined that, “It is not impossible for Russia’s influence in the Middle East to decline or even decline rapidly” and argued that Russia’s push for the expansion of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a Eurasian political, economic, and security organization, and BRICS, a grouping of leading regional economies (including Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), in the Middle East will not reverse this downward trend.

Although Russia and China superficially share a common vision of the Middle Eastern regional order, Moscow’s resistance to a junior partner role and conflicting objectives impede Sino-Russian cooperation. As strategic autonomy remains a guiding principle for Middle Eastern regional diplomacy, Russia and China will likely advance their interests in a parallel but not necessarily complementary fashion.

Samuel Ramani is a tutor of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford, where he received his doctorate in March 2021, and an associate fellow at RUSI. His first book, Russia in Africa: Resurgent Great Power or Bellicose Pretender?, was published by Oxford University Press and Hurst and Co. in 2023. Follow Samuel on Twitter @samramani2.

Photo by ALEXEI DRUZHININ/Sputnik/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.