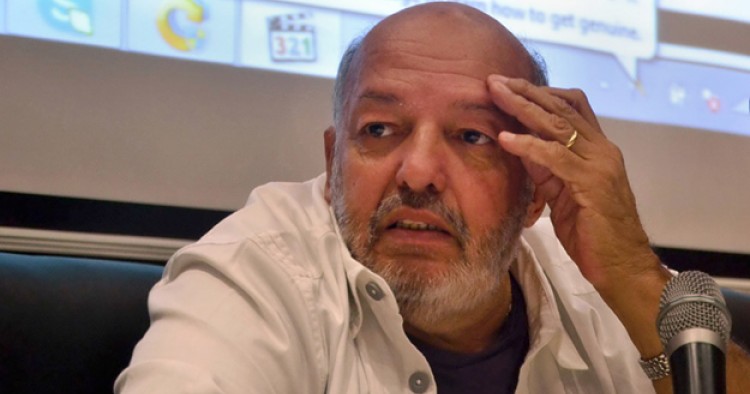

Of the numerous artists claimed by the grim reaper this year, the sudden death of veteran Egyptian filmmaker Mohamed Khan at 73 was among the most impactful. Widely considered as one of Egypt's greatest directors, the vivacious, imposing Khan had a voracious appetite for life that concealed his real age. He was a man who always seemed to be bigger than death.

Born in 1942 to a Pakistani father and Egyptian mother in the middle class Cairene neighborhood of Abdeen, Khan grew up next to an open-air cinema, which he frequented on a daily basis. He moved to England in 1956 to study engineering before dropping out after realizing that filmmaking was his true calling. He moved back to Egypt in 1963 to work as a script reader for illustrious director Salah Abou Sief—the pioneer of the first Egyptian realist wave. A year later, he relocated to Beirut where he was hired as an assistant to various Lebanese directors. The 1967 Six Day War defeat to Israel forced him to relocate to London, only to return in 1977 to Egypt and begin his filmmaking career the following year with his debut feature, Darbet Shams or Sunstroke.

An ill-fated, if fascinating, adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby came next, followed by rape thriller Al-tha'r (The Vengeance). His real breakthrough came in 1981 with Maowid ala ashaa (An Appointment over Dinner), starring the screen siren Soad Hosni, Hussein Fhamy and film icon Ahmed Zaki in the first of many collaborations with Khan.

A domestic drama about the browbeaten wife of an officious, manipulative businessman who attempts to carve out a fresh beginning for herself with an art student-turned-hairdresser, An Appointment over Dinner carried the fundamental themes that would inform the vast majority of Khan's subsequent works: the death of the middle class and the stratospheric rise of the nouveau riche; the subjugation of women; the proliferation of violence and lawlessness; the clash between desire and reality; the growing corruption of state institutions; and the demolition of traditional family values.

The themes and devices of Khan's film were shared by his cohorts from what became known as the Egyptian neo-realist wave. Khairy Bishara, Daoud Abdel-Sayed, the late Atef el-Tayeb and scriptwriter Bishir el-Deek dabbled more or less with the same subjects, with each adopting different tones and temperaments that set their narratives apart. All though emphasized on the use of natural locations—a novelty for a cinema that was born and nurtured in interior sets for nearly half-a-century.

The impact of their movies was thus quite jolting. The glorious Cairo of yore no longer persisted. The fake optimism of the pre-war years was a thing of the past.

Khan's movies were arguably the most confrontational, containing none of Abdel Sayed's whimsy, Bishara's occasional lightheadedness, or el-Tayeb's affinity for divine justice. Taer ala el tariq (Bird on the Road, 1981); Nos arnab (Half-a-Million, 1982); El harif (The Artful, 1983); Awdat mowatin (Return of a Citizen, 1986) and several other Khan films were sober portraits of emasculated men searching for an unattainable grace in a godless world.

Heaped with insurmountable praise from the local critical establishment, most of these films do not, nonetheless, hold up well today. The narratives were always overwrought and excessively melodramatic; the structures were contrived; the morally conservative politics were simplistic and preachy.

Always taken at face value and never objectively assessed, the post-infitah (economic open door policy) Egypt propagated in the neo-realist movies would prove to be a myth. In her seminal book, Popular Egyptian Cinema: Gender, Class, and Nation, film scholar Viola Shafik attests that the movies in this period "highly exaggerated the span of lower-class mobility, falsifying the fronts of social struggle by portraying the middle class caught between the new bourgeois and urban middle class," adding that "the 'ethical' reservations put forward by the old elite against the rising businessmen were the same as those displayed in committed realist films."

A comprehensive record of a transitioning Egypt, therefore, these films were not. The stories and choice of characters revealed more about the filmmakers than real life at the time.

The conventional structure Khan's movies operated under forced him to habitually deploy crime to thrust his narrative with a superfluous impetus that made them accessible to a larger audience. In the various instances when he decided to give this strategy, he ended up producing piercing character studies that rank among the finest in Arab film history.

Less confrontational, but equally ambitious, were Ahlam Hind we Kamilia (Dreams of Hind and Kamilia, 1989) and Supermarket (1990). The first is an absorbing chronicle of two maids striving to make ends meet, while the second is a low-key drama about the friendship of a failed pianist and his divorced neighbor.

The former is one of modern Egyptian cinema's finest feminist statements; a slice-of-life drama that is more authentic, more honest and more real than Khan's previous films. Naglaa Fathy assumes the role of the patriarch in her adopted family that ultimately deems men as disposable surplus. She fights, steals and uses stolen money to support her friend and daughter, and stays unrepentant throughout.

Supermarket could be regarded as Khan's most self-reflexive work: an admission of the failure of his generation to deal, or accept, the newly capitalist Egypt where status of art, culture, or even class, is no longer preserved.

In 2000, Khan scored his biggest commercial success with Ayam el-Sadat (Days of Sadat), an unbalanced, hagiographical biopic of the assassinated Egyptian president that was admired more for its production values and Ahmed Zaki's performance than for its questionable politics. The new century saw him team up with young scriptwriter, and wife, Wessam Soliman for a series of well-received romantic social dramas that were far softer than his previous films. Although he continuously struggled to find funding, he remained one of the most beloved and revered figures in the industry.

But Khan will forever be remembered for his 1980s movies; for his distinctive vision, and the passion and vigor that he instilled in the faltering local industry at the time. Khan was a man firmly attuned to the rhythm of city life—to the joys, fears, desires and uncertainties of a place and people he grew to embrace.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.