Tunisia’s July 25 hirak, or “movement,” was in the making since 2011, but perhaps we researchers were simply looking in the wrong place. This article presents a simplified account of the ideological roots of President Kais Saied’s July 25 power grab. Drawing on original and previously unused data as well as diverse sources, including a book recently withdrawn from stores,1 it offers a snapshot of the concept-map of ideas that have thus far remained hidden from the public domain.

No account of July 252 is complete without analyzing two factors. First, the two-week Facebook mobilization campaign that preceded the power grab, which I have covered elsewhere.3 Second, the ideational origins of July 25, specifically, the thought of Rida Cheheb Mekki, known as Tunisia’s “Lenin.” Obviously, this should not detract attention from the socio-political backdrop of July 25.4 Disaffection by marginalized elements has been magnified by ongoing protests across the North African country. Nondemocratic socio-economics is a mismatch for democratizing politics, while another important feature in Tunisia’s case has been the rivalry, and resulting political impasse, between the president, the chief of cabinet, and the house speaker.5

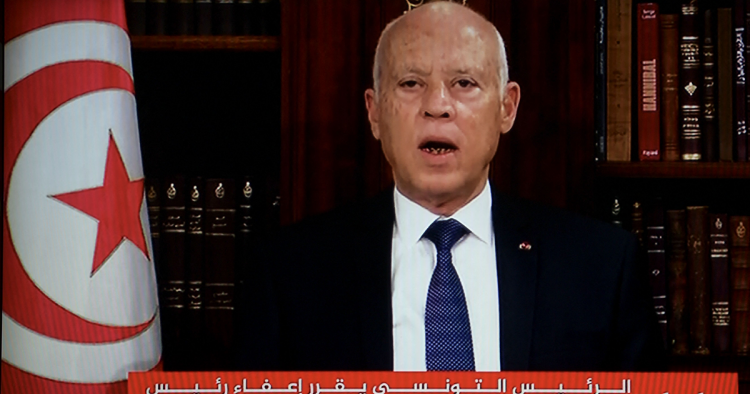

As the initial deadline of the “exceptional measures” Tunisian President Kais Saied enacted on July 25 approached, he mockingly rebuffed calls for a “roadmap” outlining his political plan. That should be self-evident, said the president, since he embodies the “people’s will.” He subsequently extended the measures indefinitely on Aug. 23, saying, “Parliament itself is a threat to the state.”6

A behind-the-scenes political adviser?

Enter Mekki, whose proclamations are an important key to understanding what makes Saied tick and what he aims to do. The leftist political activist — like Saied, not known for any resistance to Ben Ali’s dictatorship — served as “part” (he does not like to be called the “head”) of Saied’s 2019 presidential campaign. More than 22 months after the president’s landslide victory, his closeness to Saied is widely remarked upon, but Mekki insists he does not speak for the president.

With no formal or official role, Mekki nevertheless appears to be a powerful voice inside the palace. He has even said he has met with parties and civil society groups such as the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT), presumably on Saied’s behalf. He himself insists on an intense “harmony” between his and the president’s political views and outlooks. It may not be far-fetched to conclude that he is the architect of Saied’s “political project,” which the president accelerated into high gear on July 25.

Using primary sources, the major tenets of Mekki’s political vision can be pieced together. These ideas clearly correspond to Saied’s populist discourse — on behalf of “the people,” against the perpetually corrupt political class — since the fall 2019 election campaign. The two men use identical terminology, and this is no coincidence.

What’s wrong with the status quo?

So what does the president’s ideologue, “Rida Lenin,” as he is popularly known, believe? To what sort of politics does he aspire?

First, Mekki rejects the entire path Tunisia’s democratic transition has taken since 2011. This is not to say he merely faults the political class for falling short of popular expectations. He does, but so do many other political and civic actors. More than that, he has not been “on board” with the processes and institutions ushering in Tunisia’s nascent democracy. From 2011, he says, matters began to slide off-track, away from the “new politics” promised by revolutionary mobilization. For him, 2014, which is hailed as the launch of Tunisia’s democratization, was instead a definitive “deviation” from the revolution and the “people’s will.” The new constitution, election law, and presidential and parliamentary elections seven years ago set Tunisia on the wrong path.

Second, Mekki repeatedly decries the “failure” of the entire post-2011 political class and political system. He describes the past decade as one of the “disruption” of revolutionary aims and the (always amorphous) “people’s will.” On every level, he argues, Tunisia’s politicians, operating through the Second Republic’s political and electoral systems, have worked against the socio-economic and political needs of “the people” — and the state. Here he taps into widespread (and often legitimate) discontent with the political failures since 2011 to revive the economy, address regional imbalances, curb unemployment, and provide other distributive goods to Tunisia’s citizenry. Regions on the periphery have been the victims of such policies.7 The Kamour protests illustrated how marginalized communities would not settle for a democracy that fails to delivers social equality.8 Long before July 25, Tunisia’s revolution was literally “under siege.”9

Third, Mekki laments the “decay” and attacks on the Tunisian state as such. The state is in decline globally, and in Tunisia the political class and the political system have brought this about. Corruption is one manifestation of the deepening “threat” to the Tunisian state, which is falling apart at the seams. Saied’s project, Mekki claims, is to “wrest back” control of the state from those who have hijacked it with their money, through their illicit networks and manipulative politics. Such tirades about protecting the deteriorating state help set the stage for the president’s justification on July 25 for his “exceptional measures.” The state and by extension Tunisians were in “imminent danger.”

Mekki sums up Tunisia’s problems as stemming from three inter-related pathologies: the electoral system, the political system, and floundering development policies.

What is the solution?

Mekki does not stop at criticizing Tunisia’s current political situation. He consistently articulates a political vision of a quasi-Peronist direct democracy, where “the people” reign supreme. Much more common in his discourse than the democratic imperative is an unmediated popular sovereignty. Despite calling for an overhaul of the 2014 constitution, he is full of praise for Article 3, which asserts that "the people are sovereign" and their "authority" is expressed via referendums and their "representatives." To him, this is the cornerstone of his desired political system. If he (and Saied) get their way, the 2014 constitution will likely be shelved for good.

The “people,” as an undifferentiated mass, are sanctified. Their “will” has been stolen from them by the post-2011 political class in a grand theft supported by the current political system. Two concepts central to this political scheme are shar'iyyah (legal legitimacy, as through elections) and mashroo'iyyah (peoplehood, reflecting popular sovereignty). The relationship between the two is skewed, with mashroo'iyyah sorely lacking. Here Saied sounds exactly like Mekki. His local municipality election/committee plan is set to remedy the shortage of peoplehood (Article 3) in the current political system.

Too many “mediators,” such as political parties and parliament, have stood between the people and governing institutions. To remedy this situation, Mekki suggests upending the legislative branch in particular and reforming it from the “bottom up.” Each of Tunisia’s 264 municipalities should vote “on individuals” rather than party lists; according to him, this would create 264 “centers of power” and reverse the overly centralized parliamentary authority.

Mekki rejects the term lijan sha’biyyah (popular committees) as it reminds people of Libya’s late dictator Moammar Gadhafi. Yet it is not difficult to see why he and Saied — the latter most clearly in his 2019 election campaign — have prompted such comparisons in the Tunisian media and public discourse.10 Municipally elected individuals can coalesce at the regional and then the national level through some sort of national popular council that replaces parliament. Importantly, the president can stay on in this new political system, Mekki has explained. Who else will declare war and peace and ensure unity among Tunisians?

Which raises the question: With such atomization of power at the local level, who will hold the president in check?

By his own account, Mekki does not believe in the procedures and processes of liberal democracy. People around the world must move on from parliaments, inventing and enacting new forms of local, popular-based rule that rise to the occasion of this “historical moment.” In fact, Mekki positions himself as being at the cusp of a new era. In Marxist-tinged rhetoric, he sees himself as recognizing, and perhaps helping create, the “historical bloc.” This movement will be “progressive” enough for the new forms of governance that go beyond liberal institutions or right/left classifications.

Convergence or coincidence?

A perfunctory “thematic analysis”11 drawing on statements, social media, and interview data helps tentatively identify areas of ideological convergence between Saied and Mekki. These themes reveal dogmatic ideas and a number of recurring meanings that help explicate the direction of politics post-July 25. This method facilitates reading the limited data available in relation to seven themes: the people, democracy, existing political elites, the political system, parliament, and political parties. Notwithstanding this caveat, more than friendship appears to tie the two men together. Attempted here only sparingly, thematic analysis aids in understanding Saied and Mekki’s positions, feedback, and political values by answering the following questions:

- What are both men’s positions on the political changes post-July 25?

- How is the whole question of national politics constructed in relation to reforming the system?

|

THEME |

SAIED |

MEKKI12 |

MEANING |

|

CORRUPTION |

Has declared war on corruption, from monopolies and price fixing to individuals and parties |

Fighting corruption at the “heart” of Saied’s project |

Anti-corruption serves as a departure point to garner public support, re-engineer political system |

|

“THE PEOPLE” |

“The people want”: 2019 campaign slogan |

Identifies himself as part of “the people want” team Can wrest back power through new forms of political organization |

Populist discourse President claims to single-handedly represent the people’s will |

|

DEMOCRACY |

Advocate of measures such as “voting on individuals,” local-level governance |

Against liberal democracy “Parliamentary democracy … chains” people Stresses public referendums (Article 3 of constitution)

|

Common thrust toward implementation of direct democracy |

|

POLITICAL ELITES |

Frequently uses terms like al-fasidun (the corrupt type)

|

Corrupt class who hijacked the revolution

|

At odds with the “people’s will” |

|

CURRENT POLITICAL SYSTEM (2014 CONSTITUTION) |

Should be rebuilt “bottom-up”: local-regional-national power |

One of Tunisia’s 3 major problems; should be changed

|

Agreement on overhaul |

|

PARLIAMENT |

Presents “imminent” and/or “lurking danger”: justification for parliamentary freeze on July 25 |

Parliamentarism has expired everywhere; better alternatives needed Legislature’s hierarchy should be reversed: political power from the local level up

|

Obstacle that must be removed |

|

POLITICAL PARTIES |

Political independent; kept parties at arm’s length since assuming presidency Move to prosecute parties based on Audit Court’s findings |

Problematic “mediators” between people and government Political jockeying, coalitions of parties not representative of “people’s will” |

Antithetical to vision of bottom-up politics |

Political partnership?

Drawing on the above, the broad political themes and the meanings attached to them by both figures, an ideologue and a head of state, point to a strong convergence in terms of political preferences for Tunisia’s future direction. Based on a limited thematic analysis, there is some ground to state, even if only tentatively, that the two men’s partnership has enough shared ideological resonance to suggest it is contrived rather than merely fortuitous. For Mekki, Saied seems to have been the man to help achieve this vision. Thus, his enthusiasm for the current president’s candidacy, the idea for which he and others, likely “comrades” in the post-2011 movement Qiwa Tounes al-Hurrah (Free Tunisia Forces), floated in 2014. The year 2019 was a watershed, a turning point when the new could begin to replace the old. What remains to be seen, however, is Saied’s genuine willingness to walk in lockstep with an unelected, unofficial adviser who seemingly repudiates the notion of representative democracy. Saied owes his own position to the primacy of the ballot box rather than any exercise of unmediated sovereignty by the masses. For the moment, Saied may be finding it expedient to seize on leftist justifications against the post-transitional state, only to later change course in the opposite direction.

And yet it turns out the president, who has had no “political project” for over a year and a half, does indeed have one: dismantling the country’s democratic institutions, bit by bit. The “exceptional measures” enacted on the back of staged protests and on the pretext of maintaining social peace, confronting socio-economic underperformance, widespread public discontent, and political dysfunction have provided just such an opportunity. It remains to be seen how much of the ideas and ideals of Tunisia’s own “Lenin” will form the basis for the so-called “Third Republic,” if or when it sees the light of day. Rumors have been swirling and speculation mounting as to whether the president’s next move will be to incorporate Mekki and his group’s vision.13 He has laid low since July 25, with his son even denying the Facebook page with his name belongs to his father.14 Will a new party form to help carry out this vision? Do “Rida Lenin” the ideologue and Saied the commander-in-chief represent a “precarious” meeting of ideas for Tunisia’s fledgling democracy or a historical “corrective”? Saied has not given much direction as to what he plans to do, but the above must be understood as a first attempt to map out some possible preferences and priorities.

Pressure on Saied, both internal and external, is mounting. Even some of those who initially expressed support for his “exceptional measures,” such as Mohammad and Samia Abbo and her party al-Tayyar al-Dimuqrati (the Democratic Current), have publicly drawn the line at dispensing with the 2014 constitution. It may be that Mekki/Saied’s joint message of overhauling the entire political system is alarming to more actors political and civil society. They may be realizing that social capital, political acumen and performance, and trenchant problems such as corruption are to blame for Tunisia’s manifold socio-political challenges — rather than the constitution itself and the political system it promulgated. Perhaps the constitution may be simply amended and not done away with altogether. This may be a way to save face against persistent accusations and growing criticism that he has since July 25 instituted a “constitutional coup.” More than a month and a half later, Saied has failed to present Tunisians with a new political vision and a path forward. Socio-economic problems are not, in fact, disappearing since the president imposed exceptional measures. Speculation and discomfort abound.

The G-7, the EU, the U.S., and others have exerted their own versions of pressure. Many voices, including Saied supporters and Mekki himself, have decried “external intervention” in the wake of statements stressing the need to restore Tunisia’s democratic institutions. This is a legitimate, principled stance. However, it fails to take into account the intertwinement of political and economic realities and Tunisia’s dependencies within the global capitalist economy. As a heavily indebted state, Tunisia is bound to chafe under diplomatic pressure as it seeks to negotiate new loans with the IMF, for instance. The one who pays the piper dictates the tune, so to speak.

Saied’s position as president leaves little room for ideological rashness in the manner of Mekki’s political vision. There is talk in Tunis of an attempt by parliamentarians opposed to the July 25 power grab to impeach President Saied. In the absence of concrete and extensive political support, he may not be able to institute the new system on which he and Mekki appear to converge. The ideological affinities between Mekki and Saied, and the bond between the two, may not extend to forming a party on behalf of Saied’s supporters (the rumored Tunis Tureed). Implementing Mekki’s radical ideas could prove catastrophic for the country, the system, and the people. Such risks may be dawning on the president, who has most recently suggested he will amend, and not rescind, the constitution.15

For now, Tunisia, along with the international political community, waits to see what will happen next.

Larbi Sadiki is Professor of Arab Democratization at Qatar University. He is editor of the Routledge Series (UK): Routledge Studies of Middle Eastern Democratization and Government. He is Editor-in-Chief of the new Brill Journal, PROTEST. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by FETHI BELAID/AFP via Getty Images

Endnotes

- My Friend Ridha Lenin: Notes from the Biography of a Damaged Generation, by Fethi Ennesri (Tunis: Maskilyani lil-Nashr, 2020).

- Larbi Sadiki & Layla Saleh, “Tunisia’s Power grab is a Test for its Democracy.” OpenDemocracy, July 28, 2021, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/tunisias-presidential-power-grab-is-a-test-for-its-democracy/ [Retrieved: August 26, 2021].

- Larbi Sadiki, “‘Cyber Protest’: The Hidden Face-book of Tunisia’s July 25.” Sharq Forum, August 24, 2021, https://research.sharqforum.org/2021/08/24/cyber-protest-the-hidden-face-book-of-tunisias-july-25/ [Retrieved: August 26, 2021].

- Larbi Sadiki, “The 25th of July: Tunisia’s Revolution, Part 2?” AJE, July 30, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/7/30/the-25th-of-july-tunisias-revolution-part [Retrieved: August 26, 2021].

- Larbi Sadiki, “The Failure of Bargain Politics and Tunisia’s Crisis of Democratization.” Sharq Forum, August 26, 2020, https://research.sharqforum.org/2020/08/26/the-failure-of-bargain-politics-and-tunisias-crisis-of-democratization/ [Retrieved: August 26, 2021].

- Erin Clare Brown, “‘A parade of red flags’: what next for Tunisia after Kais Saied’s extension of power?,” The National News, August 25, 2021, https://www.thenationalnews.com/mena/2021/08/25/a-parade-of-red-flags-what-next-for-tunisia-after-kais-saieds-extension-of-power/ [Retrieved: September 8, 2021].

- “Tunisia’s Peripheral Cities: Marginalization and Protest Politics in a Democratizing Country.” 2021. Middle East Journal 75(1): 77-98.

- Larbi Sadiki, “For Tunisian Protests Democracy is not enough.” OpenDemocracy, July 8, 2020, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/tunisian-protesters-democracy-not-enough/ [Retrieved: August 26, 2021].

- Larbi Sadiki, “Tunisia’s Revolution under siege: When the IMF calls the shots.” OpenDemocracy, March 31, 2021, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/tunisias-revolution-under-siege-when-the-imf-calls-the-shots/ [Retrieved: August 26, 2021].

- See for example, “Interview with Rida Mekki, Ideologue and Strategist: Rediscovering President Kais Saeid,” in Elmashad, January, 11 2020: https://www.elmashhad.online/Post/details/118873/%D8%AD%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D9%85%D8%B9-%D8%B1%D8%B6%D8%A7-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%83%D9%8A-, [Accessed: 2 1 September 2021].

- Anthony G. Tuckett, “Applying thematic Analysis Theory to Practice: A Researcher’s Experience.” In Contemporary Nurse, (2005), Volume 19, No. 1-2, pp. 75–87. [DOI:10.5172/conu.19.1-2.75].

- Rida Cheheb Mekki has been forthcoming about his political views and his interpretation of what Kais Saied stands for. See, for instance Birnamej Qahwa ‘Arabi ma’ Ridha Chiheb Mekki, Al-Wataniyya, July 11, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iLTPdbrp3Rk&t=1017s; Madha Yureed Kais Saied min Harakat al-Nahda?...Ridha Chiheb Mekki Yatahaddath. Diwan FM, April 21, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jCZuY8_AjXc&t=555s; Rendevzous, S09, E.03, Attessia TV, December 25, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TNIcne-bfbg; Lil-tarikh, Attessia TV, Episode 1, December 9, 2019: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8T7fQPRNEbA, [Accessed: September 2, 2021].

- Asmaa Bacouch,. Hal Yattajih Kais Saied Nahwa Tatbiq Mashroo’ ‘Qiwa Tounes al Hurra’ fi al-Hukm? [Does Kais Saied move towards implementation of Free Tunisia Forces’ project] Tunisia Ultra, August 31, 2021, https://tinyurl.com/t7vu4js6, [Accessed: September 2, 2021].

- See intervention on Diwan FM, August 31, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6MJ1R2IBQps, [Accessed: September 2, 2021].

- See for instance Tunisian Presidency’s official Twitter account, September 12, 2021, https://twitter.com/TnPresidency/status/1436834779022991361.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.