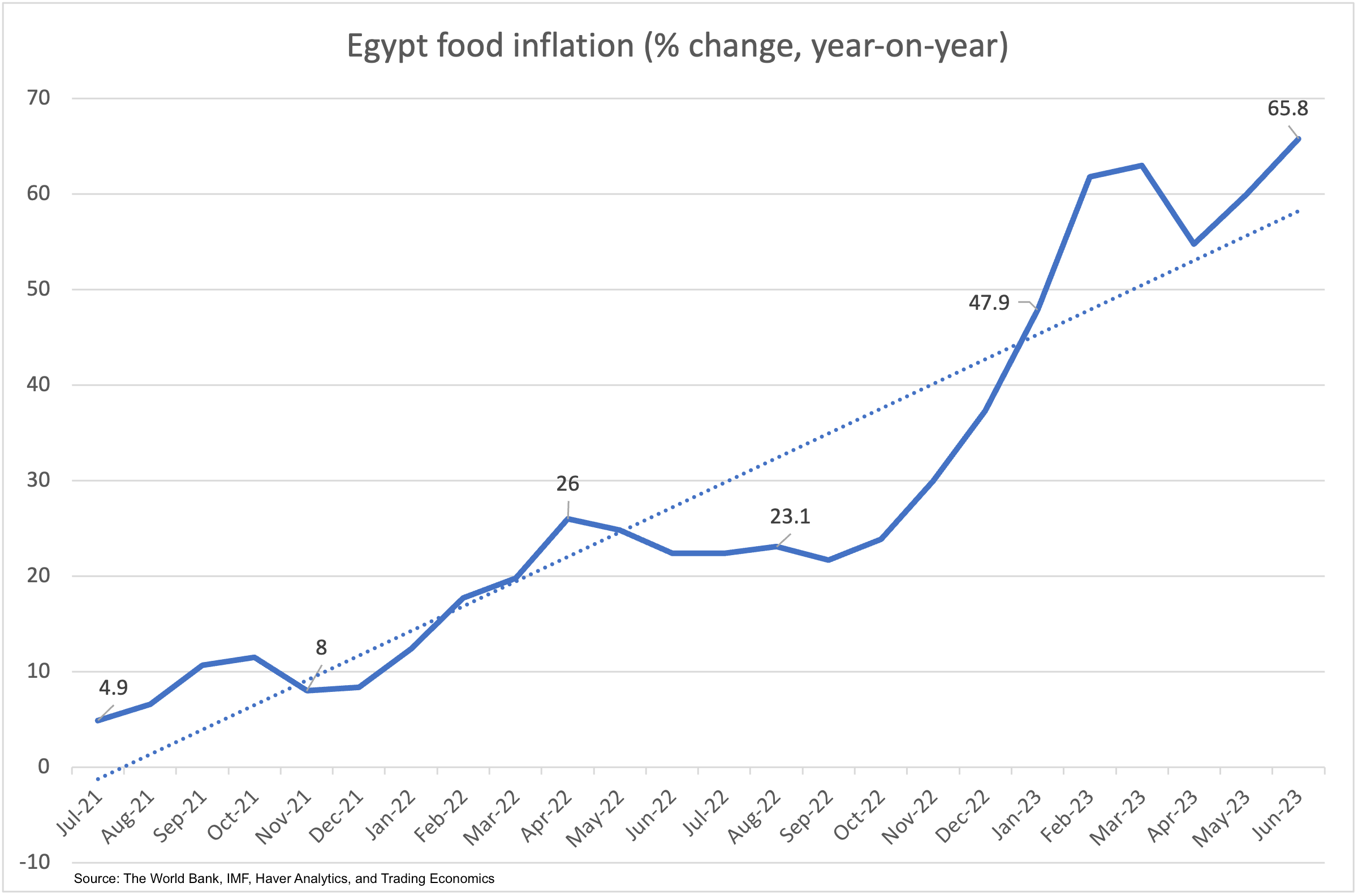

After 500 days of coping with the debilitating economic impact of Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Egypt’s economy is faltering. In June 2023, Egypt’s annual inflation rate hit an alarming record high of 36.8%, more than two and half times the 13.6% of the year prior. If inflation keeps climbing at its current pace, the Middle East’s most populous nation will enter a state of hyperinflation by year’s end. At the core of the crisis is Egypt’s fragile food security. Driving the country’s inflation juggernaut is skyrocketing food inflation, which saw food prices soar by 64.9% in June.

As a previous MEI publication warned at the time of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, “the Russia-Ukraine war has turned Egypt’s food crisis into an existential threat to the economy.” By the end of December 2022, Cairo was compelled to turn to the International Monetary Fund for a $3 billion loan to stave off a fiscal catastrophe resulting from a host of long-standing problems that were exacerbated by the loss of Ukraine as a major supplier of affordable cereal grains and oilseeds. Now, the Egyptian economy is fast approaching a tipping point and Russia’s July 17 decision to discontinue the Black Sea Grain Initiative — a move Egypt has criticized while pledging to continue importing Ukrainian wheat through Europe — will strain an already overburdened Cairo as it seeks to secure food imports for its 105 million citizens.

Egypt’s agrifood production cannot meet even half of its domestic demand for key staple products, particularly the cereal grains wheat and corn (maize). Egypt has no alternative but to increase its own domestic agrifood production, even as climate change worsens its extreme water scarcity. Recognizing Egypt’s over-reliance on global trade to feed its citizens is no longer tenable, President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi has embarked on the construction of ambitious infrastructure mega-projects to increase the water supply available for agriculture. While a necessary foundation, an infrastructure build-out alone will not be enough. Egypt must turn to the concurrent adoption of cutting-edge agritech solutions to improve the water-use efficiency of the crops themselves. To do so, Cairo must prioritize agritech as an area of strategic cooperation with the United States, Europe, and other foreign partners.

The water-food nexus

Cairo’s effort to increase domestic agrifood production rest on ramping up the output of cereal grains, which witnessed a June price jump in Egypt of 58.9%. Surging wheat and corn prices have in turn raised the cost of basic items from bread to cooking oil to budget-breaking levels. In addition to being a stabilizer in bread, corn is the main component of animal feed for cattle, poultry, and fish. Rising grain prices have helped push June 2023 meat and poultry prices to spike 92.1%. Price hikes have caused the average supply of protein in Egypt to plummet 200% in the past three years, dropping from 95.3 grams per person per day to only 30.5 grams.

The fundamental obstacle to easing Egypt’s food crisis by boosting its cereal grain output is water-use efficiency amid increasing water scarcity. While the production of a kilogram of potatoes requires 287 liters of water and tomatoes 214 liters, the amount of water needed for cereal grain production is at least five times greater, with wheat requiring 1,827 liters per kilogram and corn 1,222 liters. With its annual rainfall averaging a scant 33.3 mm, Egypt depends on the Nile River to provide approximately 90% of its freshwater consumption of about 65 billion cubic meters (bcm), over 80% of which is used in agriculture.

With intensifying heat stress and water scarcity brought on by climate change, Cairo is already challenged just to maintain its current levels of agrifood production. Egypt’s high evaporation further exacerbates the difficulties for its agricultural sector, over 99% of which relies on irrigation. Even without heat stress, about 50% of the water used in conventional flood irrigation never reaches the root system. Under conditions of heat stress, crops rely on evapotranspiration for cooling to maintain a viable temperature. Climate change projection models forecast the rise in potential evapotranspiration will increase the water irrigation demand by upwards of 13%. Absent effective countermeasures, the World Bank forecasts that climate change-driven water scarcity and heat stress will reduce Egypt’s wheat and corn production between 10% and 20%.

The decline in cereal grains production due to heat stress and water scarcity will have a commensurate impact on Egypt’s livestock production, which accounts for about one-quarter of its agricultural GDP. Chicken meat, raised on feed comprised of 70% corn, is Egypt’s largest agricultural product by value. Although popular as a cheaper alternative to more expensive red meats, chicken meat production itself requires 4,325 liters of water per kilogram. Fish, much of which is being raised in fish farms fed with fish fodder similarly comprised of corn, accounts for 25.3% of the average Egyptian household’s protein intake.

Big approaches to big problems

Egypt faces an annual water deficit of 30-35 bcm, according to Egypt’s Minister for Water Resources and Irrigation Hani Sewilam. Speaking before parliament, Sewilam blamed the water deficit for Egypt’s need to import food. The scale of the problem is enormous: Egypt’s water deficit is equivalent to about 60% of the Nile River’s water contribution to the country. To address the problem, Egypt has already adopted the National Water Resources Plan 2017-2037. The 20-year plan is a large-scale infrastructure program, whose $50 billion price tag includes the construction of numerous water desalination plants and the massive build-out and upgrade of the nation’s agricultural irrigation system.

Creating an additional water supply using seawater desalination is an unavoidable necessity for Egypt. It will also have the geopolitical benefit of reducing its vulnerability to the water losses that may occur when the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam further upstream on the Nile becomes fully operational. Yet, seawater desalination is highly energy intensive, as sea water reverse osmosis (SWRO) requires 10 times the amount of energy to produce the same volume of water as conventional surface water treatment. While prohibitive for many countries, the power generation requirement is not unmanageable for Egypt as a result of President Sisi's focus on building up the country’s electric power generation capacity. From 2016 to 2022, Egypt turned its 6 GW power generation capacity deficit into a 15 GW surplus, over 16% of which is produced from renewable energy sources. Cairo eyes building 21 desalination plants and is seeking foreign investment to help defray the $3 billion cost of the phase one development. When completed, the $8 billion project would contribute 3.21 bcm to Egypt’s water supply, roughly 10% of the current deficit.

The other major infrastructure approach is to improve Egypt’s water distribution and irrigation systems. To that end, the government is undertaking a $2.6 billion program to rehabilitate 20,000 km (12,427 miles) of the country’s canal system. The real water savings will come from replacing conventional flood irrigation with drip irrigation and other forms of modern irrigation. Using drip irrigation, water consumption can be reduced by as much as 60%, increasing crop yields from 30% to 90%. However, at a cost ranging from $1,200 to $3,000 per hectare, even basic drip irrigation systems are beyond the means of small-scale farmers. In an effort to convert half of Egypt’s irrigated farmland to smart irrigation, using drip as well as bubble, spray, or mist irrigation, Cairo has undertaken a $3 billion initiative that will allow farmers to pay for the conversion in interest-free installments over 10 years. With a cumulative cost of $14.4 billion, desalination and irrigation could reduce Egypt’s current water deficit by 20% to 70%, but it could take the rest of the decade to complete.

Agritech’s “small” solutions have big and faster impacts

Improving seed quality for high drought tolerance and water-use efficiency holds great promise, but the potential of this approach remains largely unrealized, despite some progress made during the previous decade. Egyptian farmers still cannot access sufficient quantities of quality seeds when they need them. Egypt’s Agricultural Research Center and Agricultural Genetic Engineering Research Institute both collaborate with the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) to improve wheat varieties and get them to farmers, but more needs to be done. The Beirut-headquartered ICARDA and its Egyptian partners have distributed almost 20,000 tons of certified rust-resistant and high-yielding seeds. Although these seeds have a 21-25% yield advantage over common commercial varieties, the amount distributed is sufficient to cover just 11% of Egypt’s wheat growing area. In close collaboration with the German-headquartered Global Crop Diversity Trust (the “Crop Trust”) and supported by Norwegian funding, ICARDA developed a new drought-tolerant variety of durum wheat named Jabal (Arabic for “mountain”), which was released in December 2022 to Moroccan farmers for trials.

While the ICARDA-Crop Trust Jabal variety was developed through breeding, genetic engineering techniques have also been proven successful and have found commercial application. A U.S.-Israeli-Chinese initiative centered at the University of California, Davis has used genetic editing to develop wheat plants with the right number of copies of the OPRIII group of genes to stimulate the growth of longer roots able to pull water from deeper in the soil. As the research team reported in a February 2023 article in the scientific journal Nature, the resulting wheat plants are drought resistant and produce higher grain yield.

Beyond seed development, the field of biostimulants has been achieving similar results with commercial products that are currently on the market. Without resorting to genetic modification, biostimulants are nutraceuticals that stimulate plants’ natural processes to enhance their nutrient uptake or their ability to tolerate heat and drought stress. A 2022 meta-study of biostimulant effectiveness found an across-the-board increase in crop yields ranging from 8.5% to 30.8%. Proving effective, the European Biostimulants Industry Council projects a compound annual growth rate for the European biostimulants market of 10-12%. Having been shown to help improve crop resistance to heat stress and drought, biostimulants are potentially an important solution that can be deployed in Egypt in a comparatively short timeframe.

A crop like wheat will lose up to 50% of its root system under drought conditions, hampering the crop’s water uptake and recovery once drought conditions cease. Biostimulants can render crops drought resistant by preventing any overall loss to the root system. Several companies across the industry boast biostimulant products that can increase the root systems of healthy crops by at least 30%, providing a corresponding benefit in water-use efficiency, reducing the large water loss currently experienced with conventional flood irrigation. With the cost of installing drip irrigation about five times greater than a decade’s worth of applications of biostimulants, eco-friendly biostimulants can be applied as Egypt rolls out its program to convert farmland to drip irrigation. Biostimulants and modern irrigation techniques are complementary technologies and also can be used together in a process known as “fertigation” with potentially even greater effect.

Conclusion

The fragile state of Egypt’s food security poses an existential threat to the viability of the country’s economy and the Sisi government. While emergency aid and alternative grain suppliers may forestall the country from entering the economic abyss of hyperinflation, it will not help it reverse course. Egypt’s escape from its perpetual economic catch-22 is to reduce its food imports by providing more of its own food. While Egypt’s visionary infrastructure build-out to create additional water supplies to expand domestic agriculture promises to be transformational, it is a vision that is living on borrowed time. Cairo needs to repay or refinance $20 billion in debt over the next 12 months while using its diminishing foreign reserves to import food and spend $4.14 billion on subsidies to make that imported food affordable for the population.

As the ending of the Black Sea Grain Initiative indicates, the next 500 days of the Russia-Ukraine conflict will likely see a profound worsening of the global food crisis. Cairo has little time to lose in adopting agritech solutions to avert an immediate and disastrous downturn in its own food security. To feed itself, Egypt also needs to counteract the impact of accelerating water scarcity due to climate change. The water-use efficiency achieved through agritech is crucial for Egypt’s ability to expand its agrifood production in the immediate term, making agritech diplomacy a unique opportunity for the United States to engage Cairo in a strategic partnership of vital consequence.

Professor Michaël Tanchum is a non-resident fellow with the Middle East Institute's Economics and Energy Program. He teaches at Universidad de Navarra and is a senior fellow at the Austrian Institute for European and Security Policy (AIES). You can follow him on Twitter @michaeltanchum. The author would like to thank Vicky Andarcia and Josué Burgos García for their research assistance.

Photo by Mahmoud Elkhwas/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.