President Kais Saied’s war on speculation is attempting to direct the focus of people’s anger about food shortages onto speculators. A recent emergency importation of grain has stayed off the emptying of shelves, but as the country’s treasury is drained and eventually products begin to disappear from stores again, the people's patience and faith in his new political project will wear very thin. For now, he is profiting from national exhaustion, but how long till hunger becomes anger and anger becomes a movement?

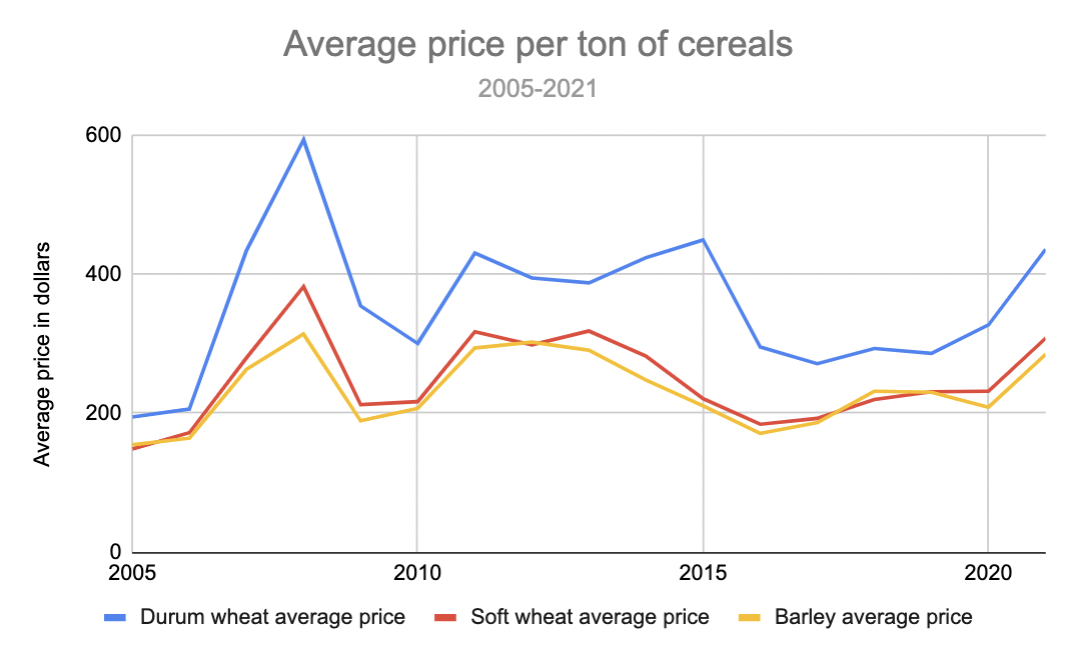

President Saied has been trying to distract Tunisians from the grim reality that the country is broke and the food subsidies that have been part of daily life since the 1970s are at the heart of the problem of food shortages. The issue has been exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, which has sent grain prices skyrocketing, but according to the National Agricultural Observatory (ONAGRI), prices have been rising sharply since last summer.

According to a recent poll by Insights TN, 95.8% of people in a sample of 865 adults polled between Jan. 30 and Feb. 8, 2022 said that they are not convinced that the government is doing a good job of keeping prices down.

President Saied launched his “war on speculation” on March 9 and passed decree law No. 14 imposing harsh new penalties, ranging from maximum sentences of 10 years for ordinary speculation to 20 years for speculating on subsidized products up to 30 years for being part of a cartel of speculators, plus hefty fines.

Since March the media has been flooded with images of policemen raiding food warehouses. The impact of these highly mediatized raids seems to be limited, however, and food shortages are still a recurring problem, as people queue outside bakeries and bakers run out of bread.

Should you scroll through the Facebook page of the Ministry of Commerce, which regularly inspect wholesalers and warehouses, you will see a stream of photos displaying piles of packets of pasta and couscous and sacks of flour that belong to alleged “speculators,” accompanied by moralizing captions admonishing them and aimed at supporting the president’s narrative. You will also see that the Ministry of Commerce has turned off comments because people want to know where all this confiscated food is disappearing to, as they are not seeing any real change in the bakeries or shops where, if you do find flour or semolina, you are only allowed one kilo. In Ramadan, when every night is feast night, this is a real problem.

Amnesty International has drawn attention to the fact that this new law also includes a prohibition on the spreading of “false news” about food supplies that could cause people to panic buy, stockpile, or speculate. According to John Thorne, a researcher with Amnesty Tunisia, “Ambiguous terms such as ‘false news’ are open to very broad interpretation, and laws that criminalize speech based on such terms threaten freedom of expression as guaranteed by international law.”

The Syndical Chamber of Wholesalers told me that over 100 of their members had been raided by armed police after issuing a statement protesting against the armed raids. It was a very worried man who told me that “we are finding a solution with the minister” and that “everything would be fine with the new decree law.” He accepted that police would accompany the inspectors from the Ministry of Commerce, a seeming complete volte-face from their previous, more defiant stance.

According to the Association for the Fight Against the Rentier Economy in Tunisia (ALERT), the real impact of Russia’s war in Ukraine and the blockade of grain from Mariupol will not fully impact Tunisia until May. ALERT is a relatively young organization, made up of business people, accountants, industry workers, and economists, including Houssem Saad, who told me, “There is no speculation, just food shortages.”

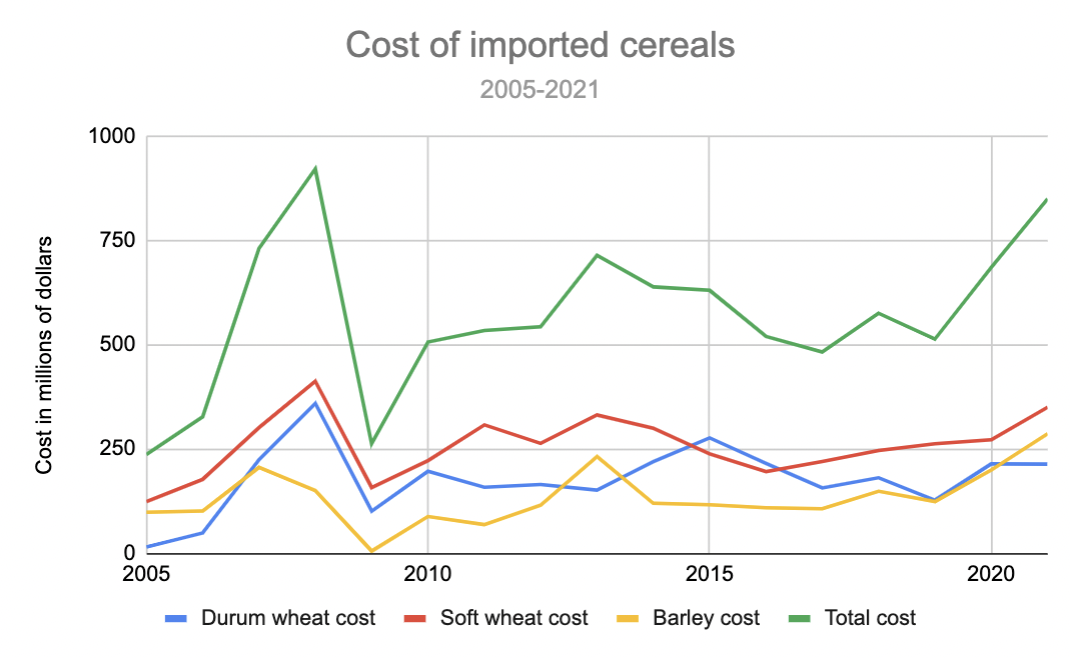

In fact, if we look at data from Tunisia’s Office of Cereals, there are visible correlations between shortages and periods of economic depression, such as 2009, following the world financial crisis; 2016, which was a very difficult year economically for Tunisia; and 2020-21 during the pandemic and subsequent slight recovery.

If we look at data from the end of 2021, we can see that imports of wheat were somewhat lower than normal. Despite having once been the breadbasket of Rome, Tunisia is not self-sufficient in wheat, particularly bread flour.

Tunisia claimed it had sufficient grain stocks to last until May or June, yet on the first day of Ramadan 17 bakeries in the city of Kairouan alone were forced to shut due to flour shortages. Thus, it is clear there is a difference between government statements about grain reserves and the availability of flour, particularly in the non-subsidized sector.

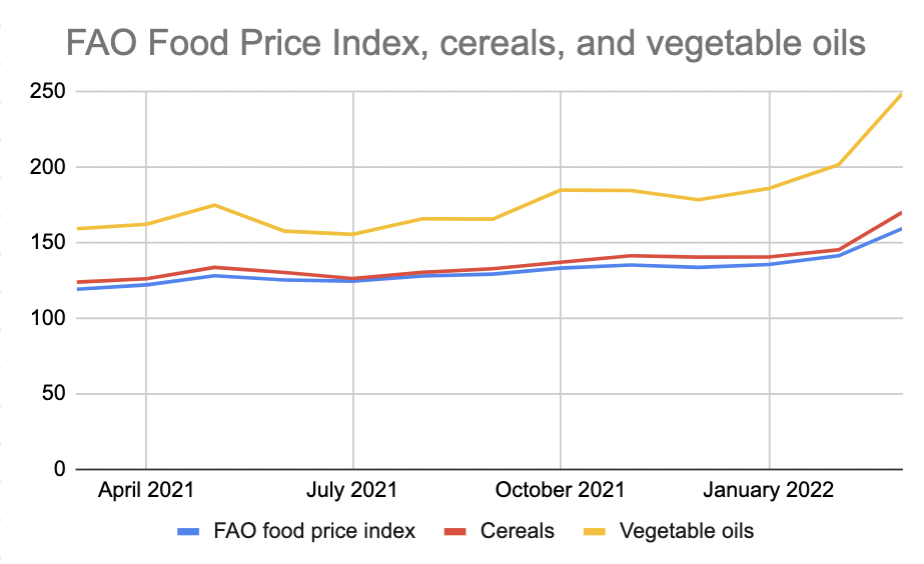

According to a recent poll from Insights TN about bread availability, 47% of respondents said that in a 10-day period prior to the poll bread was always available, but 42% said that they couldn’t find bread on one or more days, including 17% who couldn’t find bread for three or more days. The picture for vegetable oil, which is also subsidized, is much worse, with 46% of respondents saying that they could not find it in the 30 days prior to polling. The U.N. FAO's Vegetable Oil Price Index rose 23.2% in March, driven by the impact of the war in Ukraine, which is the world’s largest exporter of sunflower oil.

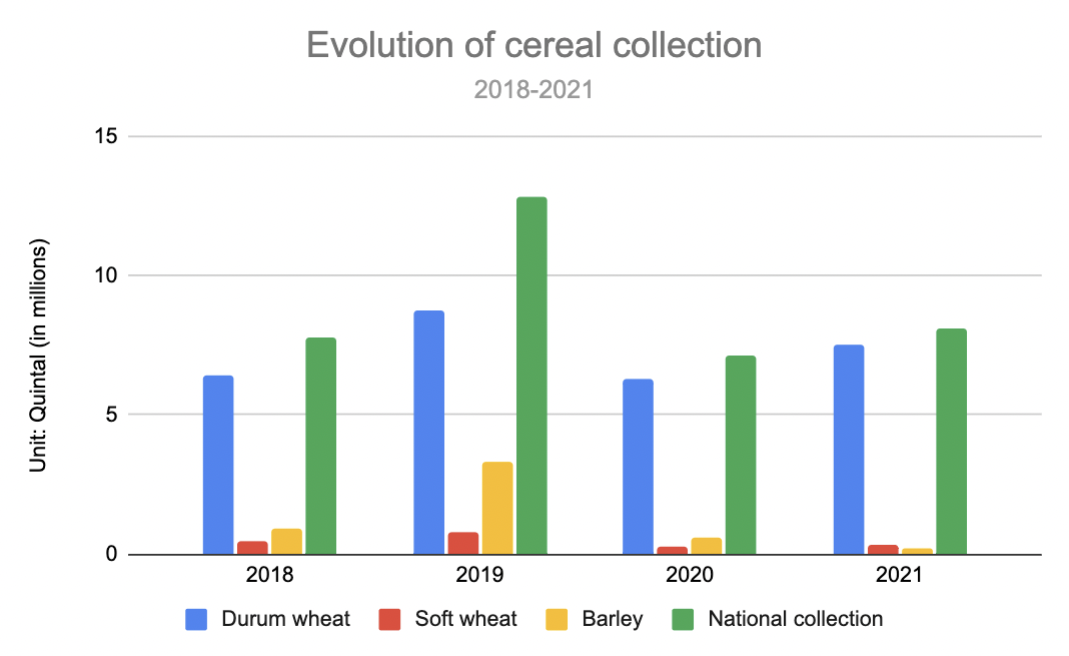

Unlike wealthier countries such as Saudi Arabia, Tunisia does not have any reserves of grain stockpiled to help it weather tough times, but it is a wheat producer. Tunisia produces between 70% and 90% of its durum wheat supplies, and this feeds its local pasta industry.

However, Tunisia only produces 10-30% of its bread flour and is therefore heavily reliant on foreign imports and vulnerable to market fluctuations. Rather than increasing production of grain, a report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture notes that the amount of land seeded to grow grain has been falling. According to a 2021 report by the academic climate consortium Cascades, “Tunisia is considered to be one of the countries most exposed to climate change in the Mediterranean."

Tunisia’s economic position continues to weaken, with the dinar crossing the 3 dinar to U.S. dollar mark on April 9, and this situation is further compounded by the rising price of oil, which is increasing the cost of transport.

About half of Tunisia’s grain imports come from Ukraine, and according to a recent report from the International Crisis Group, Tunisia is in debt to Ukraine to the tune of $300 million. Regardless of the logistical issues created by the war, Ukraine apparently will not accept another order from Tunisia without it paying 50% upfront. Tunisia has already run into problems with payment when six ships were blocked in the port of Sfax in December due to non-payment. The amount due was eventually paid, but food shortages are a manifestation of Tunisia’s serious economic problems and the state's debilitated spending power.

Tunisia buys its grain — wheat, durum for pasta and couscous, and barley — through one central entity, the Cereals Office. The grain is then distributed to a limited number of milling companies, many of which, like Randa and Warda, own pasta producers that take a specific percentage according to their assigned quota. A portion of this grain is allocated for producing subsidized food products, most notably bread.

Soft wheat flour is used primarily by what are known as “traditional” bakers, who mainly bake the standard baguette, which is sold for just 200 millimes ($0.06). This price is sacrosanct and has remained the same since the presidency of Habib Bourguiba, who first introduced food subsidies in the mid-1970s. When he tried to raise the price to comply with reforms required by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the result was the 1984 Bread Riots. Since then no government has dared touch the price of bread, though President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali managed to cut costs by shrinking the size of the baguette.

ALERT says that these quotas are monolithic, that in recent years only one new milling company has managed to get a quota of grain to mill, and that grain imports and milling are part of the rentier-based economy that has been steadily strangling Tunisia for years.

ALERT also says the government-subsidized bread is nutritionally poor. It is made with low-quality, highly refined white flour and so-called bread improvers, and uses the highest amount of salt in the Mediterranean region. It is a far cry from the traditional wholegrain, hand-milled, small round loaves called tabouna that have sustained Tunisians for centuries.

Much of the focus has been on the agri-food sector, but if ALERT’s hypothesis is right, what we are seeing is the net result of a much deeper problem: an economy that has stagnated due to family-based monopolies facilitated by the state and compounded by both internal tariffs and external unfavorable trade deals. This situation is exacerbated by the administration and unreasonably high barriers to entry, stifling the market and barring would-be entrepreneurs. MP Yassine Ayari, a member of the left-leaning Amal Party, told me that his research had found that to open an ordinary bakery, an entrepreneur needed to submit a file of no less than 60 documents. Matters that should be straightforward, like filing taxes, are complicated by antiquated paper processes. The litany of painful administrative procedures is so long that it would send any Tunisian entrepreneur racing to catch the next boat to Lampedusa.

Bad practice within the food supply chain causes further problems for consumers. Fares Belghith, the founder of a new e-commerce app Kamioun, which launched in 2020 and supplies the small local grocers called attar, says, “Tunisia has poor supply chain management.” The Kamioun app was designed to resolve small shops’ inventory problems due to erratic service and high-pressure sales tactics by distributors and brands. According to Belghith, a leading dairy brand might say that “if you want to buy my yogurt, you need to buy my water and my milk,” adding that these illegal practices are accepted as normal in Tunisia.

Tunisia is also drowning in public debt. It accounts for 92.7% of GDP, up from 64.2% in 2016. Furthermore since President Saied’s power grab on July 25 last year, the country has suffered two credit rating downgrades. Moody’s downgraded Tunisia from B3 to Caa1 and it was further downgraded by Fitch from B to CCC on March 18, citing large budget deficits and heightened liquidity risk. Rising oil prices have also impacted the amount that Tunisia needs to borrow, originally set at $7 billion in the FY22 financial law.

According to ONAGRI, Tunisia has yet to feel the full economic impact of the war in Ukraine, which given the dire situation already affecting the country is deeply worrying. Tunisia has neither resilience nor the resources to shield itself from a full-on economic depression.

At the moment the mood in Tunisia is depressed. Normally Ramadan nights are full of joy and music and everyone is out in the streets, but this year things are markedly subdued. Discontent is muted, muttered in private conversations. Although Citizens Against the Coup and the Free Destourian Party have both mustered a couple of thousand in their recent protests, this is not the mass march of rebellion by any stretch of the imagination.

For now people are still reluctant to openly blame Saied for their worries; the country has not forgotten last year when parliament seemed to be spinning out of control with violent assaults and regular breaches of constitutional procedure. However, as prices continue to soar and Tunisia’s economy further weakens, Saied seems determined to plow on with his process to change the constitution by referendum and not address the economic crisis.

At the moment the sentiment is against the IMF, which is seen as holding out on Tunisia while the people go hungry, but neither Saied nor members of parliament are offering the country a serious recovery plan — one that does not fall back on old Tunisian economic tropes that leave the country in the same straightjacket of family dominated monopolies strangled by archaic business legislation and procedure that has held people hostage for decades.

Tunisia is in desperate need of a complete revamping of its economy and business environment to guarantee not just the basic necessities like daily bread, but a better quality of life and a chance for Tunisians to realize their dreams.

Elizia Volkmann is a British freelance journalist based in Tunis covering Tunisian politics, social and economic issues, as well as the wider Maghreb and Euro-med region. The views expressed in this piece are her own.

Photo by ANIS MILI/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.