This essay is part of the Middle East-Asia Project (MAP) series on “'Civilianizing' the State in the Middle East and Asia Pacific Regions.” The series explores the past and ongoing processes of Security Sector Reform (SSR) in Asia-Pacific countries and examines the steps already taken and still needed in the MENA region. See More …

Tunisia is one of Germany’s most important security partners in the Middle East North Africa region, receiving €30m annually in security support in 2016 and 2017.[1] According to Germany’s Guidelines on Sustainable Peace,[2] security sector reform (SSR) should be pursued in ways that improve governance, are gender sensitive, and effectively “deal with the past.”

However, reviewing Germany’s security assistance to Tunisia in the past few years reveals a mixed record in relation to these principles, and highlights different driving concerns. Such an examination is especially relevant in light of the coming German SSR Strategy, expected to be released within a month. The SSR Strategy will present a standalone vision of how Germany intends to use SSR in its global development commitment,[3] and will harmonize the visions and activities of the Federal Foreign Office, and Ministries of Interior, Defence, and Economic Cooperation and Development when it comes to the support they give to other states’ security sectors.

Considering the growing value of German security support globally, Tunisia offers important lessons for the effective promulgation of the SSR Strategy both in the Tunisian case and in the region as a whole. This article addresses two overarching questions: First, to what extent do Germany’s security assistance programs in Tunisia conform to the guiding principles it has established? And second, what does this mean for making Germany’s new SSR Strategy both principled and effective?

1. Germany’s Bolder Security Policy in the Region

Germany’s considerable commitment to security sector assistance and reform in Tunisia is part of a wider pattern of increased German spending on security support globally. Although it is challenging to collate the information for all the relevant programs, Philipp Rottman at GPPI calculates that Germany’s spending through its three major international security support programs rose from €20m in 2015 to €155m in 2017, in addition to €150m spent annually on the Afghan security forces.[4]

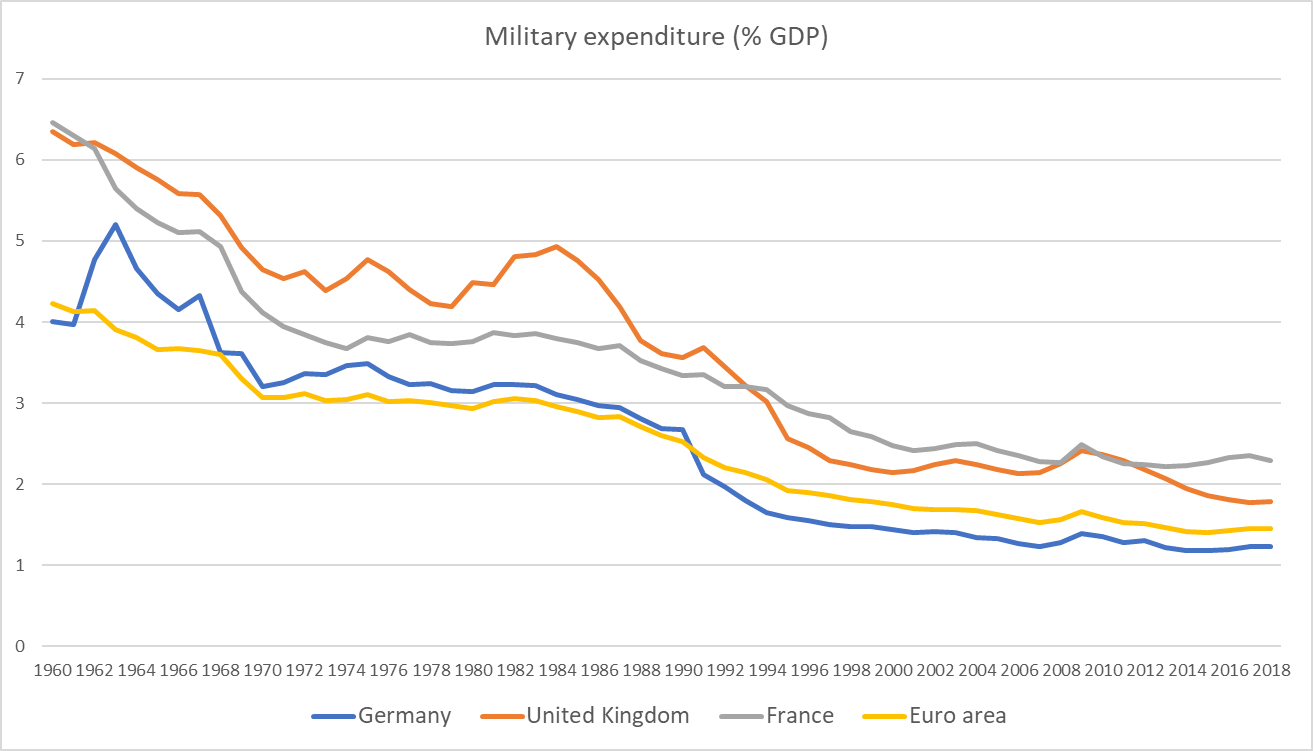

Increased spending on support for the security sector of other states should not be confused with changes in German defense spending more broadly, which is a topic of current controversy within the US-Europe argument over NATO spending commitments. German spending has stayed more or less steady in the past decade, averaging 1.25% of GDP;[5] and a planned increase for 2019 would raise the figure to 1.35%.[6]

Figure 1. German Defense Spending Source: World Bank Group

Source: World Bank Group

The increased spending on security sector support is part of the delivery of a bolder German security policy vision for the region. Until the mid-2010s, Germany’s position was at most anti-interventionist, as manifested in the country’s opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and its abstention in 2011 on UNSC Resolution 1973, which created the legal framework for enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya.[7]

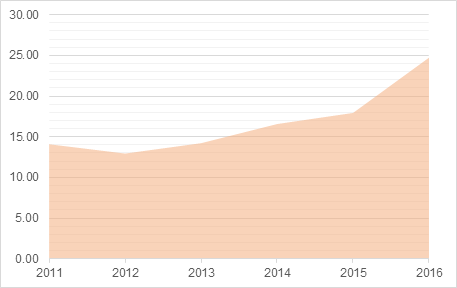

By the mid-2010s, Germany’s posture had shifted. At the 2014 Munich Security Conference, Foreign Minister Walter Steinmeier and Minister of Defense Ursula von der Leyen stated Germany’s ambition to adopt a more active role in its Southern and Eastern Neighborhood, a posture crystallized in security terms in the 2016 Defense White Paper.[8] These ambitions became manifest in the Bundeswehr’s arming and training of the Peshmerga for their fight against ISIS in 2016.[9] (To place this in context with wider overseas spending changes post-2011, Germany’s ODA spending rose between 2012 and 2016 from $14b to $24b annually.)

In addition to a greater willingness to project hard power in the region and engage directly in security issues, these developments also reflect Germany’s self-assertion among its partners in security terms. Multilateralism does indeed remain a cornerstone of German foreign policy. (This includes its security assistance work in the border missions through the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) in Libya and Iraq, its support for the Palestine Authority’s police, and its contribution to the Geneva Centre For Security Sector Governance (DCAF)[10] Trust Fund for North Africa (TFNA), to which Germany provides funds earmarked for Tunisia and Morocco.[11]) However, it is clear that, since the 2016 White Paper, Germany has become more willing to initiate and lead security assistance-type programs,[12] a security entrepreneurship that is evident in the size of Germany’s support for Tunisia’s security sector.

Figure 2. German Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) Spending

Source: World Bank Group

Within this context, Tunisia is considered a key recipient of German security support because of its location with respect to migration routes, the multidimensional terrorism threat, and the relatively conducive environment it presents for internationally sponsored development efforts.

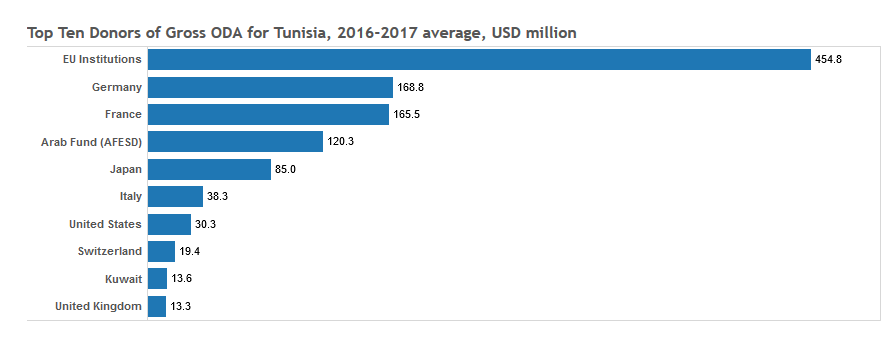

Figure 3. Germany’s Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) Compared

Source: OECD

German SSR and security assistance goals

Germany’s motivations in pursuing a more robust security strategy in MENA stem from several domestic and international factors. Key among them are the consequences of Germany’s refugee policy. The Federal Republic hosts the largest number of Syrian refugees in Europe, and eyeing the “arc of crisis from Morocco to the Caspian Sea,”[13] sees advantage in “fighting the root causes of displacement” and “stabilizing host regions,”[14] with a focus on the Middle-East and North Africa.[15] Germany has pursued stabilization vigorously, emerging as the number one ODA donor to the MENA region on average for the years 2016-2017.[16] At the same time, however, Germany has also emerged as arguably the most active supporter of the EU’s strategy of “border externalization” (i.e., extraterritorial measures aimed at containing the flow of refugees and other migrants).[17]

Figure 4. Distribution of Syrian Refugees and IDPs in Europe and Middle East North Africa in 2017

Source: Pew

Germany applies a number of humanitarian, development, diplomatic and security approaches towards these foreign policy goals. However, there is no standalone strategy for how security sector reform should be applied. In terms of a set of principles for security engagement, the closest available package is outlined in the guidelines “Preventing Crises, Resolving Conflicts, Building Peace.”[18] This commits Germany to carrying out SSR in accordance with a number of principles, including:

- By helping to build security agencies that are effective and responsible and that are part of legitimate and democratic political structures, i.e. the commitment to good governance.

- By working in a way that involves the perspectives and needs of men and women, i.e. by working in a gender sensitive manner

- By working in a way that effectively deals with the past.

Examining Germany’s record in Tunisia against these three commitments offers a way of evaluating its success so far and identifying how the new SSR Strategy might be implemented to reflect more fully Germany’s principles.

German SSR and Security Assistance Footprint in Tunisia

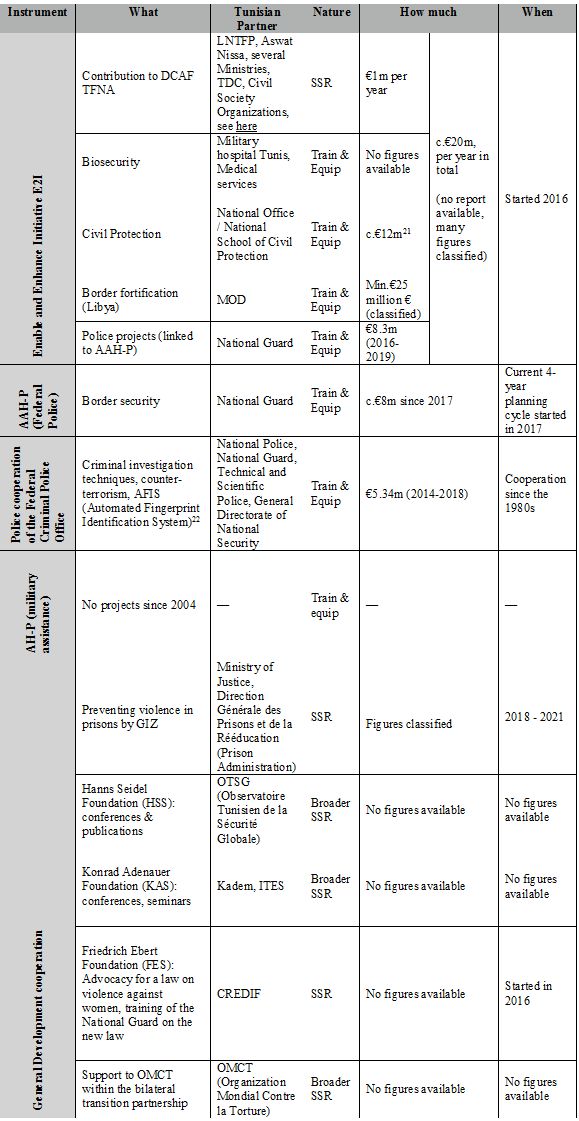

Gathering information and figures about Germany’s SSR projects in Tunisia is not straightforward, as the Federal government does not publish a comprehensive report on its measures related to SSR and security assistance. While information on military assistance is largely classified, civilian projects with possible relevance to SSR are dispersed because they are carried out by the many different actors engaged in German development cooperation. Accordingly, they must be picked out one by one. The chart below provides an overview of projects which Germany labels as SSR and which are related to SSR but have not been mentioned as such.

In an answer to a parliamentary request regarding German involvement in SSR programs, the Federal government mentions four instruments:[19] military assistance (AH-P), police assistance and training (AAH-P), the new Enable and Enhance Initiative (E2I),[20] in addition to general development cooperation, of which the three latter are currently applied in Tunisia.

Figure 5. German SSR and SSR-Related Projects

AAH-P

The AAH-P is the Federal Government’s police train and equip program affiliated with the Tunisian Ministry of Interior (MOI). It is planned in a four-year cycle (2017-2021) with an annual budget of €5m for five countries (Tunisia, Morocco, Nigeria, Palestine and Jordan), of which the biggest share has gone to Tunisia since 2015.

The Tunisian partner within the AAH-P is the National Guard, which is responsible for border security jointly with the army. As a first step, the northwestern region of Jendouba has been selected as “model region,”[23] where effective border security enforcement has been supported; German support has also moved south, to the region of El Kef. On the Libyan border, the National Guard is deployed about 30km from the border due to the existence of a military zone, but also receives training and equipment for border security. The maritime department of the National Guard received training and equipment in 2016.[24]

Figure 6. Germany's ODA and security sector support to Tunisia (in millions of euros)

E2I

The Enable and Enhance initiative (E2I) was created in 2015 and implemented the next year as a flexible security assistance tool, aimed at “enabling trustworthy partners”[25] to take responsibility for their own security in their region, which — in contrast to the existing assistance programs — can also include lethal weapons.[26] Tunisia is one of the focus countries of the initiative, besides Mali, Iraq, Jordan, Nigeria (and since 2018, Niger and Burkina Faso).

The E2I has its own title in the Federal budget plan (€100m in the first and €130m per year thereafter) and is planned annually, building on demands of its partner countries. This tool also allows donations to other organizations such as DCAF, which receives €1m annually for their work in North Africa from E2I funds. DCAF also works on SSR in its political terms and on a wide range of topics, going from communication with citizens over strategic planning to media, parliamentary oversight capacities and gender considerations.[27]

Besides the contribution to DCAF, the rest of the annual €20m E2I budget for projects in Tunisia is spent on improving biosecurity and the establishment and training of voluntary networks in civil protection. Since 2017, the German Federal Police has received funds from the E2I for its police cooperation projects in Tunisia.[28] In sum, except for DCAF, the E2I is largely a train and equip tool.

Other

Not officially listed by the federal government as SSR, some German development actors run projects which could be defined as SSR in broad terms. For example, one of the German political foundations working closely with the Tunisian civil society, the Friedrich-Ebert-Foundation, has supported the Centre de Recherches, d'Etudes, de Documentation et d'Information sur la Femme (CREDIF) in its advocacy work for law N°58 on violence against women as well as in its police training program.

Since 2017, CREDIF has trained National Guard officers at the Kairouan police school on the new law, which came into effect in 2018.[29] Other German political foundations cooperate with CSOs on topics which touch upon SSR in a broader sense.[30] The state-owned development agency GIZ is currently working on project on the prevention of violence in prison, funded by the Foreign Office. On request, the Foreign Office confirmed that this project lies at the intersection of SSR and the promotion of the rule of law and therefore could be considered a part of German SSR strategy, but declined to disclosed information on the budget or other SSR projects (classified).[31]

Since 2015, international donors have coordinated their security assistance in the G7+ mechanism, where Germany took the lead on borders. Frank Vornholdt of the German Ministry of Interior considers the G7+ a great improvement in coordination, a view that contrasts with that of scholars who argue that G7+ members still try to push forward their national agendas.[32]

2. Analysis

Security sector reform or security assistance?

In sum, based on the available information, German SSR involvement in Tunisia shows a prevalence of security assistance over political SSR in Tunisia.

Improving governance: limited application

In its guidelines document, Germany states the need for “(re)building effective and responsible security forces embedded in functioning and legitimate political structures accepted by the population.”

Such concepts come under the more general notion of good governance, a concept of particular relevance in the Tunisian security sector today. The call for justice in the security sector was a prominent motivation in the 2011 uprising in Tunisia because of the centrality of the police agencies to Ben Ali regime.[33] The police were a target of the demonstrators’ ire, and the revolutionary momentum had some early successes in governance terms.[34] However, systematic changes around governance have not yet been fully achieved. And while the 2014 Constitution specified the neutrality of the police, it arguably provides an insufficient guarantee of civilian oversight.[35] Furthermore, the standing parliamentary committee that is tasked with overseeing the security sector has been criticized for lacking the power, skills and experience to do so properly. In the larger context of the disappointing Transitional Justice process (frequently labelled “TJ”), no police officers have been found guilty for the deaths of protestors. While human rights standards have improved in many senses, mistreatment by police is an issue that still needs to be addressed.[36]

Factors in the slowdown of governance reform relate to the wider political economic conditions in Tunisia since 2011. Economic growth and employment proved more pressing concerns for the general public and political actors than security sector reform. Furthermore, the security sector itself has been able to resist change, which to some degree it seems to have considered threatening to its capability to meet security challenges such as terrorism. Indeed, the Ministry of Interior has shown considerable institutional cohesion in relation to the authority that the legislative and executive branches were able to impose. In addition, the emergence and consequent politicization of police unions created a bulwark to changes led by the legislative or executive branch, creating a difficult and politicized context for SSR in Tunisia.

Germany’s direct response to the shortfalls in the good governance of the security sector within this challenging setting is limited. While the political nature of the factors slowing down good governance adds a layer of complexity for international SSR support, it certainly does not preclude support on governance issues. However, the vast majority of German funding to security support does not go to projects that work directly on the systematic governance problems. Reviewing the E21 suite of projects alone, shows that only approximately 5% of funding goes to DCAF while the lion’s share of the entire German portfolio are train and equip style. Even if they include elements of rule-of-law and human rights considerations within their trainings; importantly, they have no built-in traction on the systematic issues.

This is not to denigrate the work that Germany supports on systematic governance issues through its €1m funding to DCAF through the North Africa Trust Fund. DCAF’s focus recognizes the importance of this systematic issues, for instance working to support the Special Commission on Security and Defence since 2014. The effectiveness to date of this oversight committee is debatable,[37] but the important point is the work recognizes the systematic issues. In another instance, DCAF has started work on supporting the complaints mechanism, and supported the use of forensic evidence in torture investigations.

The risk of such a focus on 'train and equip'-style programs is not just related to the relative neglect of programming that improves governance. International SSR practice has demonstrated that assistance that is not conditioned on improved governance can actually worsen security provision by strengthening security forces without reforming them, and even by making them more autonomous of civilian and legislative oversight. The latter is a charge that has been leveled at international security programming in Tunisia.[38]

Indeed, looking simply at the figures, it is the fortification of the Libyan border that takes the largest share of the budget. Aside from the above-mentioned critique regarding the shortfall of focus on systematic governance issues, this prioritization appears to lack coherence. The aim of the AAH-P program is to “contribute directly to the fight against illegal migration” while having a “positive influence on migration dialogues and readmission-issues with other states.”[39] However, it is not Tunisia’s borders with Libya and Algeria that are most relevant in this respect. While Tunisia is indeed a transit and destination country for irregular migrants, it is Tunisians who make up the largest group of irregular migrants to Europe.[40]

Figure 7. Germany’s AAH-P spending.

Gender Sensitivity

After 2011, two major gendered security issues have received public and international attention in Tunisia: violence against women and violations of LGBTQ rights. When engaged through research studies in Tunisia, approximately half of women say they have experienced domestic violence;[41] more than half have experienced violence in the public space. In most of the cases this came in the form of sexual harassment, but also included physical and psychological violence.[42] For women, turning to the security forces often can be the last resort when experiencing violence, as many women regard police as incompetent. According to one study, only 31% of women stated that they could easily resort to the police or National Guard in case of a security problem, in contrast to 61% of all respondents.[43] The family or community, and not the security agencies, is the first call.[44]

Participation of women in the security sector is low. For instance, under 7% of the employees in the Tunisian Ministry of Defense (MOD) are women (figures for the MOI were not available).[45] In general, nominations of women to state offices decreased from 30% in 2014 to 15% in 2018.[46] After years of feminist advocacy, the ratification of law N°58 on violence against women was widely praised, but the hopes and expectations it raised have not yet been fully met. Civil society organizations have criticized the fact that of 126 newly created special police units charged with crimes against women and children only 16 are headed by women, and that no budget has been allocated to the implementation of the law so far.[47]

Despite the 2014 constitution’s guarantee of all citizens’ equal rights and right to physical integrity, same sex relations is criminalized by Article 230 of the Penal Code. Advocating for the improvement of women’s security and the inclusion of a gender within a binary framework (male/female) into SSR is more straightforward than for progressing LGBTQ rights and safety. LGBTQ organizations face a challenging context. The association Shams was threatened to be shut down by the government earlier this year for the seventh time in its history.[48] With a sentence up to three years in prison and police still relying on forced rectal exams — even after Minister for Human Rights Mehdi Ben Gharbia had announced a ban on the practice in 2017)[49] — people identifying as LGBTQ people face considerable threats to their personal rights and security on a daily basis. And here, the security forces are often perpetrators rather than protectors of their rights.

In 2018, 120 trials based on Article 230 were documented, which likely excludes a large number of unreported cases. Cases of prisons are known where homosexual and non-binary people are systematically kept in separate buildings and are not allowed to receive visitors.[50] Testimonies of victims of state repression show the traumatizing and life-threatening results of the police practices concerning LGBTQ people.

According to Mounir Baatour, the president of Shams, “The situation for LGBTQ has deteriorated since 2011. They have become more visible and so has homophobia within the ISF.”[51] Baatour is making a bid for the presidency that is controversial in Tunisia and within the LGBTQ community. He supports the effort to give technical support to security forces, but argues for it to be conditioned on the security agencies’ respect for LGBTQ human rights and the integration of this topic into their training. In contrast, a member of the association Mawjoudin does not believe that trainings would make a significant difference, as long as Article 230 remains and the police are not held accountable.[52]

Examining Germany’s record in terms of gender-sensitive SSR, the contribution through DCAF is salient. DCAF is working on gender in SSR, through a cooperation with the association Aswat Nissa on the implementation of UN resolution 1325.[53] Furthermore, DCAF supports the Tunisian National League of Police Women (LNTFP), a women police officer’s union.[54] Not listed as SSR explicitly by the German government, the Friedrich-Ebert-Foundation (FES) has supported CREDIF in its advocacy for Law No.58 as well as for its police training on this law.

However, despite these elements regarding women, the German government does not seem to approach gender-sensitive SSR strategically by making a gender sensitive notion of security central to its work. Human rights in relation to sexual orientation do not play a role in German police training in Tunisia. There is instead an assumption that respect of LGBTQ human rights will be transferred osmotically. According to Vornholt, equal treatment of all people is at the basis of German police work and is therefore always transmitted through trainings. Yet when asked about the practice of rectal examinations, he had no knowledge of and doubted its occurrence.[55]

There are also conceptual underpinnings to this gap. The projects funded by Germany related to gender and security understand gender mostly in a binary sense and do not consider sexual orientation — except for Aswat Nissa, which calls for a decriminalization of homosexuality.[56] However, it is difficult to give Germany full credit for these activities.

Dealing with the past

In the Guidelines on Preventing Crises, within the section on SSR, stands the statement, “In order to gain the trust of all population groups, it is paramount to conduct internal reforms and establish processes of dealing with the past.” The principle of dealing effectively with the past is of great relevance to Tunisia, where the police were an important instrument of repression and control in the Ben Ali regime. In addition to the crimes perpetrated under the old regime, a host of police misconduct and criminal cases in the more recent past (the post-2011 era) have also yet to be dealt with.[57]

Observers see these two tallies as linked and see the continuity in security agencies’ impunity as a large part of the failure, or at least incompletion, of the Transitional Justice process. Beyond the criminal justice left undone, these unresolved cases are a source of the bad blood between the police and the general population. (A 2018 survey indicated that three quarters of the population have little or no trust in the police.)[58] Such a bad relationship contributes to other barriers to SSR, including an unwillingness on both the part of citizens and security officers to collaborate on security and a retrenchment of the security services on accountability and transparency principles.[59]

Germany has its own very particular experience in dealing with the past, and has given a lot of support to the transitional justice process through German Foundations,[60] GIZ and DCAF. Through such projects, it is this principle that has perhaps been best observed out of those reviewed here, but overall it is difficult to assess Germany’s performance at this juncture. Part of the reason for this is because the primary formal vehicle of Tunisian transitional justice — the Truth and Justice Committee — has only recently released its report. This document, which took four and a half years to review 50 years of cases, was published in five volumes in late March 2019. It has faced much institutional resistance, from parts of the state, including the security sector, and the depth of its impact is not certain.

3. Policy

Germany’s opportune position

Germany’s record in delivering support to the Tunisian security sector according to its own SSR principles is mixed, and specifically in governance, their application so far has been quite weak. However, German policy has great potential because of the country’s unique position in Tunisia that marks it out from other donors. Historically, German experience in SSR through domestic work post-unification, and in the Balkans and Eastern Europe has created a deep and relevant set of technical skills and knowledge of the whole process of SSR.

In addition to the EU’s strong reputation as a regional player in Tunisia, Germany enjoys particular repute for technical ability and democratic commitment that is not cloyed by past colonial encounters or controversial foreign policy postures elsewhere in the region. This augments a perception in Tunisia that Germany responded quickly to the 2011 Revolution with sincerity and resource.[61] Indeed, the reality of the swiftness and size of the German commitment to the Tunisian transition since 2011 has given it a strong position within the development field as a whole, and notwithstanding debates over how principled its security sector work has been, it also has a strong working relationship with state security actors. Altogether, this gives Germany huge potential as a positive actor in Tunisian security provision.

To make the most of these opportunities, and to build a new era for German SSR through the forthcoming SSR strategy, it is important to look critically at its record so far in Tunisia.

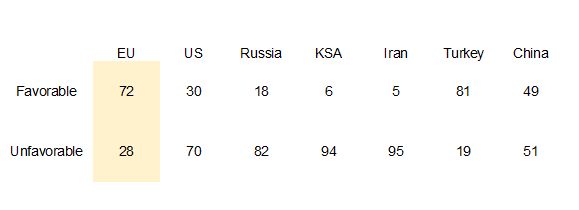

Figure 8. Tunisian perceptions of Europe

Note: Respondents answered the question, 'For each of the following countries, please tell us if your attitudes are favorable or unfavorable.' (n = 841)

Source: Zogby Research Services, Middle East Public Opinion, 2018.

Recommendations

- Make governance a real priority. The Tunisian security sector faces major issues with governance — the most critical part of SSR. However, only a small portion of German security support works directly on this issue. Deepened support could be offered to the parliamentary committee for oversight. Support should also be considered for the recommendations of the Truth and Justice Committee regarding improving police internal disciplinary measures, creating an independent complaints body to investigate police abuse and misconduct and increasing transparency in police facilities through the use of CCTV. Germany’s strong position as a development actor in Tunisia allows it more leverage than it currently exercises for conditioning its security support on real reform.

- Make gender-sensitivity more than a buzz-word. It is a difficult task to do gender-sensitive SSR without making it a buzzword and a mere diversity management strategy, where women function as tokens and LGBTQ security issues remain unaddressed. This is no surprise, as the security sector in Tunisia, just as in Germany are masculine in a double sense: they propagate masculinist notions of security and peace but also are de facto dominated by males. When strengthening the security sector, Germany must be aware that “the military [and ISF] is an important institutional producer of a specific type of militarized masculinity that often hinders more co-operative and inclusive approaches to security.”[62] Germany should therefore opt for the support of alternative approaches to security, which do not reproduce exclusive and male-defined logics of peace and security. As for LGBTQ, the ISF often represent a factor of insecurity rather than security. Germany could support initiatives that inform LGBTQ people about their rights when in contact with the police, such as their right to access to a lawyer and their right to refuse rectal exams, which are illegal.

- Continue to work creatively on dealing with the past. Just like the process of justice for those mistreated and killed under the Ben Ali regime is incomplete, so is the task of dealing with the regime’s institutional legacy in the security sector. Supporting the recommendations laid out for the security sector by the Truth and Justice Commission will be important in cultivating better relations between the police and the public.

- Improve transparency and information availability. The process of researching this paper has shown clearly the difficulty of gathering official data on German activity relating to security sector support, which is dispersed and, for the most part, has been made available through parliamentary requests made by the opposition. This situation appears unlikely to be the product of guile given that, to date, there is no standalone cross-departmental SSR strategy. With the advent of the strategy, a central data management system should be put in place and adequately resourced. The sheer amount of government money spent on these programs is a strong argument in terms of fiduciary accountability. In addition, improving availability of data enhances prospects for research to assess progress, creating opportunities for strategy perspectives, monitoring, evaluation, learning and adaptation for the Federal Government. Such transparency would buttress Germany’s moral coherence in future attempts to improve the transparency and accountability of the security sector in Tunisia and elsewhere.

- Enhance knowledge of context and partners. The context of the Tunisian security sector is complicated and changes quickly; an increased German footprint should mean a greater German capacity to understand and respond. For instance, partners should be chosen with great care. Human rights violations by partners, such as violations against LGBTQI persons through the ISF in the Tunisian case, should not be ignored. The German federal government has the duty to conduct a broad context analysis which goes beyond actors of the security sector and includes other stakeholders like civil society organizations. The involved German authorities need to have an interest in who their partners are.

- Ensure anti-migration policies do not undermine SSR goals or be driver of support to the security sector. The German Federal Government, especially the traditionally conservative Ministry of the Interior, pursues an anti-migration policy with its security assistance programs in Tunisia and elsewhere. Opting for securitized responses to migration like border externalization contributes to a continuum of violence for migrants throughout their journeys. This focus also has the potential to contradict real local security needs, especially in those communities where socio-economic conditions are tied to movements across the borders. Moreover, security assistance should not be used as leverage in negotiations on migration deals. Germany should not let its potential in supporting SSR in Tunisia get undermined by its anti-migration policy goals, but approach SSR in its political and not technical terms. This should be reflected in the spending of the budget line E2I, which is a more flexible tool and can be used on other than SA, as the contribution to DCAF shows.

- Increase support to the implementation of law against violence against women. Law No. 58 presents an opportunity to improve access to justice for women and a chance for Germany to enhance its commitment to gender-sensitive security. The factors that have impeded its fullest implementation have been identified, outlining the contours of the required support.

- Find a shared understanding of SSR goals and coordination. Throughout this research, the impression has been that different departments of the German government involved in the support to the Tunisian security sector (Federal Foreign Office, Ministry of Interior, and Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development) have different perceptions on what the goal of Germany’s security support measures in Tunisia are. While the Ministry of Interior states clearly that migration control is a major aim, the Foreign Office seems more concerned about a spillover of the conflict from Libya and counterterrorism. Meanwhile development cooperation workers in Tunisia (for example in the German Foundations) fear a further securitization of development. The new German SSR Strategy should therefore result in a better common understanding of the goals and principles of SSR among the German actors.

[1] Data availability makes calculating these figures difficult. This number is taken form Konstantin Bärwaldt “Strategy, Jointness, Capacity: Institutional Requirements for Supporting Security Sector Reform,” Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Berlin (November 2018): 34, http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/14813.pdf.

[2] Federal Government of Germany, “Guidelines on Preventing Crises, Resolving Conflicts, Building Peace,” https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/290648/057f794cd3593763ea556897972574fd/170614-leitlinien-krisenpraevention-konfliktbewaeltigung-friedensfoerderung-dl-data.pdf.

[3] The previous framework for SSR dates to 2006 and has not remained current in light of ministries’ enlarged mandate for global SSR. See “Sicherheit für Frieden – Eine neue deutsche Strategie für Sicherheitssektorreformen (SSR),” Peacelab.blog, April 24, 2018, https://peacelab.blog/2018/04/sicherheit-fuer-frieden-eine-neue-deutsche-strategie-fuer-ssr; and “Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung” (2006): Interministerielles Rahmenkonzept zur Unterstützung von Reformen des Sicherheitssektors in Entwicklungs - und Transformationsländern.

[4] Philipp Rottman, “Lots of Assistance, Little Reform,” Global Public Policy Institute, November 16, 2018, https://www.gppi.net/2018/11/16/lots-of-assistance-little-reform.

[5] World Bank Group data, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=DE.

[6] “Germany informs NATO of huge defense budget increase: report,” Deutsche Welt, May 17, 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/germany-informs-nato-of-huge-defense-budget-increase-report/a-48770380-0.

[7] Germany at the time had observer status. Germany did however provide considerable support for ISAF in Afghanistan.

[8] The 2016 White Paper, “Strategic Review and Way Ahead,” is available at https://www.planungsamt.bundeswehr.de/portal/a/plgabw/start/grundlagen/weissbuch/!ut/p/z1/hY_LDoIwEEW_hm2ngSjori58hRAT8NFuTMFaNKUlpYLx661xZaJxdnPnzMkMMDgA07y_SO4uRnPle8rGx1mSFmk4CcNiNcOYLLIwiuNltNhi2MH-H8L8GP8ogiEXGqh3xL8dI8iBAbvynt9Ra6xTwiFevW4EWnN9UmJjKvIOPKgkUG9dA5PKlO83iC6jRAKz4iyssOhmfVw713bTAAd4GAYkjZFKoMo0Af62UpvOweGThLaZJ1k26h-p2D8BzXiWQQ!!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/#Z7_B8LTL2922TIB00AGN2377H3GU5.

[9] In addition, Luftwaffe Tornados were deployed on reconnaissance over Syria and Iraq, and the Frigate Augsburg was sent to the Eastern Mediterranean to escort the French aircraft carrier FS Charles de Gaulle as it carried out strikes on ISIS. “German frigate protecting French aircraft carrier concludes ISIS mission,” Naval Today, November 15, 2016, https://navaltoday.com/2016/11/15/german-frigate-protecting-french-carrier-concludes-isis-mission/.

[10] Geneva Center For Security Sector Governance (DCAF), https://www.dcaf.ch/.

[11] Federal Foreign Office, Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) website: https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/en/aussenpolitik/europa/aussenpolitik/gsvp-start-node?openAccordionId=item-209180-0-panel.

[12] Daniel Keohane, “Constrained Leadership: Germany’s New Defense Policy,” CSS Analyses in Security Policy 201 (December 2016): 2-3, https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/CSSAnalyse201-EN.pdf.

[13] Jana Puglierin, “Germany’s Enable & Enhance Initiative: What is it about?” Federal Academy for Security Policy Security Policy Paper 1 (2016), https://www.baks.bund.de/sites/baks010/files/working_paper_2016_01.pdf.

[14] Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, “Helping refugees build a future: Tackling the root causes of displacement, stabilizing host regions, supporting refugees,” http://www.bmz.de/en/publications/type_of_publication/information_flyer/information_brochures/Materialie315_flucht.pdf.

[15] Donor Tracker, Germany, https://donortracker.org/country/germany?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI7snZ3Prr4wIVxJ-zCh08oAC2EAAYASAAEgIFqfD_BwE.

[16] Donor Tracker, https://donortracker.org/.

[17] For a discussion of the EU strategy, see Bill Frelick, Ian M. Kysel, and Jennifer Podkul, “The Impact of Externalization of Migration Controls on the Rights of Asylum Seekers and Other Migrants,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 4, 4 (2018): 190-220. Regarding Germany’s actions to boost and militarize border security in third countries, see Mark Akkerman, “Expanding the fortress: The policies, the profiteers and the people shaped by EU's border externalisation programme,” Transnational Institute, May 11, 2018, 68, https://www.tni.org/en/publication/expanding-the-fortress.

[18] Federal Government of Germany, “Guidelines on Preventing Crises, Resolving Conflicts, Building Peace,” September 2017, https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/1214246/057f794cd3593763ea556897972574fd/preventing-crises-data.pdf.

[19] Drucksache 18/11458: Deutsches Engagement im Bereich der Sicherheitssektorreform, March 7, 2017.

[20] In German, “Ertüchtigungsinitiative.”

[21] €6.4 million in 2016-2017. A similar amount is expected for 2018-2019.

[22] EU Migration and Home Affairs, Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS), https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/european_migration_network/glossary_search/automated-fingerprint-identification_en.

[23] Interview with Frank Vornholt, MOI Germany, Berlin, July 10, 2019.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Puglierin, “Germany’s Enable & Enhance Initiative What Is It About,” 1.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “Security sector development in Tunisia - Country Assessment and Results,” DCAF Trust Fund for North Africa, 2017 report, https://aidstream.org/files/documents/IATI---TFNA-Tunisia-2017-20180713010724.pdf.

[28] Email Frank Vornholt, Ministry of Interior, July 17, 2019.

[29] FES internal study on Gender and SSG, Rapport d’activités CREDIF 2015/2016, http://www.credif.org.tn/images/bulletin/rapport_final.pdf.

[30] Example of a publication: OTSG/FHS (2017). "The Tunisians and their police: Is another relationship possible?" http://www.hssma.org/de/publication.cfm?id=291.

[31] Email Foreign Office, July 15, 2019.

[32] Ruth Hanau Santini and Giulia Cimini, “The politics of security reform in post-2011 Tunisia: assessing the role of exogenous shocks, domestic policy entrepreneurs and external actors,” Middle Eastern Studies 55, 2 (2019): 225-241, DOI: 10.1080/00263206.2018.1538971.

[33] Derek Lutterbeck, “Tool of rule: the Tunisian police under Ben Ali,” The Journal of North African Studies 20, 5 (2015): 818-831.

[34] For instance, the so-called “political police” were dissolved in 2011 and eleven prominent security directors were dismissed.

[35] Haykal Ben Mahfoudh, “The Security Sector in Tunisia after the Uprising and in 2013,” Carnegie Endowment, January 23, 2014, 10, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/The_Security_Sector_in_Tunisia_after_the_Revolution_and_in_2013.pdf. On the other hand, DCAF considers that, “The constitution provides a solid basis for democratic governance of the security sector.” “Security sector development in Tunisia: Country Assessment and Results Monitoring,” DCAF Trust Fund for North Africa, 2017, 25. https://aidstream.org/files/documents/IATI---TFNA-Tunisia-2017-20180713…

[36] “Tunisia: Investigations into deadly police abuses must deliver long awaited justice,” Amnestry International, April 4, 2019, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/04/tunisia-investigations-into-deadly-police-abuses-must-deliver-long-awaited-justice/.

[37] DCAF itself notes, “Certain distrust towards the ARP’s oversight role in matters of security still remains. This represents a challenge to a proper parliamentary oversight of the security sector.” DCAF report for 2017, 59.

[38] Moncef Kartas, “Foreign Aid and Security Sector Reform in Tunisia: Resistance and Autonomy of the Security Forces,” Mediterranean Politics 19, 3 (2014): 373-391.

[39] Jahresbericht Bundespolizei, 2018, 54, https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/veroeffentlichungen/2019/bundespolizei-bericht2018.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2.

[40] According to a study drawing on Italian Interior Ministry data by the Migration Policy Institute, between January and early October 2018, there were 4,472 unauthorized Tunisian arrivals in Italy. Meanwhile, according to a 2018 Mercy Corps survey and study on Sub-Saharan migrants in Tunisia, "Most respondents interviewed aimed to reach Tunisia when they left home, with only a few coming to Tunisia with the intention to transit to Europe or elsewhere in the region." Luca Lixi, “After Revolution, Tunisian Migration Governance Has Changed: Has EU Policy?” Migration Policy Institute, October 18, 2018, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/after-revolution-tunisian-migration-governance-has-changed-has-eu-policy; “Tunisia, country of destination and transit for sub-Saharan African migrants,” Mercy Corps, October 30, 2018, https://reliefweb.int/report/tunisia/tunisia-country-destination-and-transit-sub-saharan-african-migrants-october-2018.

[41] Office National de la Famille et de la Population (ONFP), “Enquête nationale sur la violence à l'égard des femmes en Tunisie,” 2010, http://www.medcities.org/documents/10192/54940/Enqu%C3%AAte+Nationale+Violence+envers+les+femmes-+Tunisie+2010.pdf. Only limited data is available on this topic.

[42] Centre de recherches, d'études, de documentation et d'information sur la femme (CREDIF), “La violence fondée sur le genre dans l'espace public en Tunisie” (Tunis: Editions du CREDIF, 2016) 71, http://maghreb.unwomen.org/-/media/field%20office%20maghreb/documents/publications/2016/12/la%20violence%20fonde%20sur%20le%20genre%20dans%20lespace%20public%20%20tunisie.pdf?la=fr&vs=5438.

[43] Réseau Alternatif des Jeunes – Tunisie (RAJ)/DCAF, “Youth perception of human security at the local level,” 2018, 37, https://www.raj-tunisie.org/a-study-on-youth-perception-of-human-security-at-the-local-level/?lang=en.

[44] CREDIF, “La violence fondée sur le genre dans l'espace public en Tunisie,” 71.

[45] E.B.A., “Tunisie: les femmes au ministère de la défense représentent moins de 7%,” Kapitalis, October 4, 2018, https://www.kapitalis.com/tunisie/2018/10/04/tunisie-les-femmes-au-ministere-de-la-defense-representent-moins-de-7/.

[46] Aswat Nissa, “Étude sur l’intégration de l’approche genre dans la législation tunisienne relative au secteur de la sécurité entre 2014-2018,” 2019, 25, http://www.aswatnissa.org/pdf/Etude%20sur%20l%E2%80%99int%C3%A9gration%20de%20l%E2%80%99approche%20genre%20dans%20la%20l%C3%A9gislation%20tunisienne%20relative%20au%20secteur%20de%20la%20s%C3%A9curit%C3%A9%20entre%202014-2018.pdf.

[47] “Loi organique n°2017-58, relative à l’élimination de la violence à l’égard des femmes,” http://www.legislation.tn/sites/default/files/news/tf2017581.pdf. See “Tunisia: Landmark Step to Shield Women from Violence,” Human Rights Watch, July 27, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/07/27/tunisia-landmark-step-shield-women-violence; and “En Tunisie, la nouvelle législation donne espoir aux femmes victimes de violences,” Jeune Afrique, January 25, 2018, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/depeches/535884/societe/en-tunisie-la-nouvelle-legislation-donne-espoir-aux-femmes-victimes-de-violences/. For CSO criticism, see Rihab Boukhayatia, “Violences envers les femmes: Y a-t-il une volonté politique? Aswat Nissa en doute,” Huffpost Maghreb, January 1, 2019, https://www.huffpostmaghreb.com/entry/violences-envers-les-femmes-y-a-t-il-une-volonte-politique-aswat-nissa-en-doute_mg_5c34991ee4b05d4e96bc71e8.

[48] “Tunisia: Authorities must end shameful attempts to shut down prominent LGBTI organization,” Amnesty International, February 28, 2019, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/02/tunisia-authorities-must-end-shameful-attempts-to-shut-down-prominent-lgbti-organization/.

[49] “Tunisia: Privacy Threatened by ‘Homosexuality’ Arrests,” Human Rights Watch, November 8, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/11/08/tunisia-privacy-threatened-homosexuality-arrests; and Alex Bollinger, “Tunisia pledges to stop forced anal examinations of gay and bi men,” LGBTQNation, September 24, 2017, https://www.lgbtqnation.com/2017/09/tunisia-pledges-stop-forced-anal-examinations-gay-bi-men/.

[50] “Absence of a systematic review and publication of arrests and judgments based on Article 230,” ADLI State of Individual Liberties 2018, Tunis, March 2019, http://www.adlitn.org/sites/default/files/1._rapport_etat_des_li_2019_version_integrale.pdf; and Sarah Benali, “Bit Syouda: Ce pavillon LGBTQ+ de la prison de Mornaguia,” Huffpost Maghreb, March 3, 2019, https://www.huffpostmaghreb.com/entry/bit-syouda-la-derniere-residence-dune-codetenue_mg_5c7c073ae4b075435338b3f1.

[51] Telephone Interview, Berlin, July 5, 2019.

[52] Interview, Berlin, July 31, 2019.

[53] "DCAF and Aswat Nissa cooperate on the implementation of 1325 Resolution and gender mainstreaming in Security Sector Reform," DCAF, June 24, 2018, http://www.dcaf-tunisie.org/En/activite-partenaires/dcaf-et-aswat-nissa-cooperent-en-faveur-de-la-mise-en-oeuvre-de-la-resolution-1325-et-de-lintegration-de-lapproche-genre-dans-la-reforme-du-secteur-de-la-securite/77/10332.

[54] "Security sector development in Tunisia - Country Assessment and Results, 2017 report,” DCAF, https://aidstream.org/files/documents/IATI---TFNA-Tunisia-2017-20180713010724.pdf.

[55] Interview, Berlin, July 10, 2019.

[56] “Étude sur l’intégration de l’approche genre dans la législation tunisienne relative au secteur de la sécurité entre 2014-2018,” Aswat Nissa, 2019, 35, http://www.aswatnissa.org/pdf/Etude%20sur%20l%E2%80%99int%C3%A9gration%20de%20l%E2%80%99approche%20genre%20dans%20la%20l%C3%A9gislation%20tunisienne%20relative%20au%20secteur%20de%20la%20s%C3%A9curit%C3%A9%20entre%202014-2018.pdf.

[57] “70eme anniversaire de la Déclaration universelle des droits de l’Homme: Le chemin reste long pour concrétiser les objectifs et les principes de la déclaration,” December 18, 2018 (Multiple organizations), http://omct-tunisie.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/70-ANS-DE-LA-DUDH_CP.pdf.

[58] This rate compares closely to confidence in Parliament and is not unusual in terms of public perceptions of state organs. "Middle East Opinion,” Zogby Research Services, 2018, 10.

[59] Sam Kimball, “Tunisia’s Authoritarians Learn to Love Liberalism,” Foreign Policy, June 14, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/06/14/tunisias-authoritarians-learn-to-love-liberalism/.

[60] Germany has a particular civic system of political foundations carrying out international development work. Currently, there are six political foundations, each of which is close to a party represented in the parliament. They receive federal funding relative to their party’s election results, and are active in democratic education in Germany and in development cooperation. They do not act on behalf of the German government, but can receive funding from it. See https://www.bmz.de/en/ministry/approaches/bilateral_development_cooperation/players/political_foundations/.

[61] Laura-Theresa Krüger and Edmund Ratka, “The Perception of European Policies in Tunisia after the Arab Spring,” L'Europe en Formation 1, 371 (2014): 9-25, https://www.cairn.info/revue-l-europe-en-formation-2014-1-page-9.htm#pa33.

[62] For a feminist critique of Gender and Security see Cilja Harders, “Gender and Security in the Mediterranean,” Mediterranean Politics 8, 2-3 (2003): 54-72, DOI: 10.1080/13629390308230005.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.